June 9, 2017

Report:

Office of Audit and Evaluation

Abbreviations and acronyms

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- ADRP

- Agricultural Disaster Relief Program

- BRM

- Business Risk Management

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Report

- GF

- Growing Forward

- GF2

- Growing Forward 2

- FPT

- Federal-Provincial-Territorial

- OAG

- Office of the Auditor General

- OAE

- Office of Audit and Evaluation

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PPMRMS

- Program Performance Measurement and Risk Mitigation Strategy

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

Executive summary

Background and profile

The AgriRecovery Framework was implemented as a national agricultural disaster relief strategy in 2006. The federal share of this federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) Framework is administered under Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's (AAFC) Business Risk Management (BRM) suite of programs, by the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program (ADRP). While other BRM programs are designed to address production and income losses, AgriRecovery is focused on helping affected producers with the extraordinary costs necessary to recover from natural disasters and resume business operations as quickly as possible.

The AgriRecovery Framework is jointly administered by FPT governments. It specifies how the federal government will work with a province or territory that requests assistance in response to a natural disaster. The Framework outlines specific criteria that must be met to trigger a disaster response under AgriRecovery.Footnote 1

The ADRP provides the federal response to natural disaster events through joint federal and provincial/territorial assessments and initiatives.

Key findings

The evaluation found that there is an ongoing need for AAFC to provide agricultural disaster relief, particularly given the general consensus in research literature that extreme and unpredictable weather events are expected to increase in frequency over time. Evidence indicated that the federal role in the AgriRecovery Framework is appropriate, as it provides an effective national mechanism to address agricultural disasters and contributes to consistent and coordinated responses across jurisdictions. The ADRP continues to align with federal priorities and departmental strategic objectives, including the BRM outcome of "mitigating financial risk and the impact of natural disasters while still allowing for adaptation to market signals" and the AAFC Strategic Outcome of a "competitive and market-oriented agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products sector that proactively manages risk".Footnote 2

While the ADRP had implemented a number of changes in the period covered by the evaluation to improve timeliness, the trade-off between the need for initiatives to be implemented quickly and the need to comprehensively assess the situation against the Framework's criteria for assistance presents an ongoing challenge. At the time of the evaluation, the ADRP had begun development of a risk-based approach to assessments, taking into consideration common risks and challenges related to the AgriRecovery assessment process, including: the urgency of notifying producers of assessment results; the complexity of the event in question; the availability of data related to the event; and the potential costs of a disaster response. This risk-based approach is expected to improve the timeliness of lower-risk AgriRecovery initiatives.

In assessing the ADRP's performance, the evaluation found that the program has achieved its immediate outcome of: helping producers cover the extraordinary costs related to disaster recovery and that producers are undertaking the activities necessary for recovery. While incomplete performance reporting precluded a full assessment, evidence indicates that the ADRP is progressing toward achieving its intermediate outcome of helping disaster-affected producers resume business operations and/or mitigate the impacts of the disaster as quickly as possible. The ADRP could work with impacted provinces and territories to improve their collection of and reporting on performance measurement data in their final reports to the ADRP (through, for example, surveys of producers, contact with industry representatives, or analysis of producers' financial situation, as appropriate) to better assess performance against this intermediate outcome.

With respect to efficiency and economy, the direct delivery costs for AgriRecovery initiatives appear reasonable in most cases, and the total costs of administering the ADRP have declined since 2012-13.

1.0 Introduction

This report presents the findings of the Evaluation of the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program (ADRP), which is the program that provides the federal share of disaster assistance to agricultural producers under the federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) AgriRecovery Framework. This evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the ADRP and the federal involvement in the AgriRecovery Framework, which is administered by the ADRP.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE) conducted the evaluation as part of AAFC’s Five-year Departmental Evaluation Plan (2014-15 to 2018-19). The evaluation fulfills the requirement under the Financial Administration Act that all grant and contribution programs be evaluated every five years.

1.1 Evaluation scope

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the ADRP, as required under the 2009 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) Policy on Evaluation. The evaluation addresses the five core evaluation issues outlined in the 2009 TBS Directive on the Evaluation Function associated with the relevance and performance of the ADRP:

- continued need for the program;

- alignment of the program to government and departmental priorities;

- alignment of the program to federal roles and responsibilities;

- program achievement of expected outcomes; and,

- program demonstration of efficiency and economy.

The ADRP was previously evaluated by the OAE in 2011. It was also the subject of an internal audit in 2012 and an audit by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) in 2013. The current evaluation assessed the ADRP activities undertaken since the previous OAE evaluation, from 2011-12 to 2014-15. During the period covered by the evaluation the ADRP operated under two FPT agricultural policy frameworks: Growing Forward (GF) (2008-2013) and Growing Forward 2 (GF2) (2013-2018). AAFC updated and refined the performance measures for the ADRP following its renewal under GF2 in 2013. The evaluation assessed the ADRP initiatives against the performance measures in place at the time they were undertaken. The evaluation findings will be used to inform a possible renewal of the program beyond 2017-18.

Given the numerous assessments of the ADRP and AgriRecovery Framework in recent years, this evaluation report places greater emphasis on findings since the ADRP implemented changes to the Framework under GF2. For initiatives undertaken under GF, the evaluation sought to identify lessons learned to inform ongoing program delivery.

1.2 Data collection methods

The following data collection methods were used as part of the evaluation:

- Literature review: This line of evidence included a review of reports and articles published between April 2011 and November 2014, including disaster-related policies, responses and impact analyses in Canada and other countries. It also involved a media scan and analysis of coverage focused on AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken between April 2011 and November 2014. The literature review contributed to the assessment of the relevance of the ADRP.

- Program document review: The evaluation included a review of ADRP and AgriRecovery foundational documents, as well as departmental and federal government reports, to assess the relevance of the ADRP. An in-depth review of the changes that have been made to the AgriRecovery assessment criteria and the ADRP performance measures since 2011-12 was conducted as part of the document review.

The ADRP files on AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken from 2011-12 to 2014-15 were reviewed, including disaster assessments, memoranda, and provincial reporting. This review contributed to the assessment of program performance.

-

Key informant interviews: A total of 41 semi-structured interviews were conducted as part of the evaluation of the ADRP, of which 23 were on the subject of the ADRP’s relevance and performance, 18 on the performance of selected AgriRecovery initiatives reviewed through the case studies, and 13 that contributed to both lines of evidence. Table 1 below presents a breakdown of interviews conducted as part of the evaluation, by key informant group and line of evidence. The case studies are described in greater detail below.

Table 1: Contribution of interviews to lines of evidence Key Informant Group Line of Evidence: Key Informant Interviews Line of Evidence: Case Studies Line of Evidence: Key Informant Interviews and Case Studies Total Federal Officials 6 0 7 13 Provincial Officials 3 0 6 9 Producer Associations 0 7 0 7 Producers 0 11 0 11 Academic 1 0 0 1 Total 10 18 13 41 - Case studies: Four case studies were conducted as part of the evaluation to examine the federal response to agricultural disasters through the AgriRecovery Framework. The case studies provided an in-depth understanding of: program delivery; whether intended outcomes were achieved; efficiency and economy of initiatives; and lessons learned. The four case studies included a review of five AgriRecovery initiatives and one AgriRecovery assessment that did not result in an initiative, as follows:

- Selected forage-related AgriRecovery Initiatives (2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative, 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative and the 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Initiative);

- 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative;

- 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative; and,

- 2012 Ontario Tree Fruit Frost Damage Assessment (no initiative undertaken).

The case studies were selected by the OAE in coordination with the ADRP to assess the AgriRecovery response in a variety of situations, as well as to examine areas of particular interest. Efforts were made to reflect the diversity of AgriRecovery initiatives, including factors such as geography, affected commodity group, nature of the disaster, value of payments to producers, and number of producers receiving assistance. These cases were not intended to be representative of all AgriRecovery initiatives and results cannot be generalized.

Each case study included a review of ADRP files on the assessment or initiative, as well as documentation and interviews with stakeholders. A total of 31 interviews were conducted for the case studies, including with federal officials (7), provincial officials (6), representatives of producer associations (7) and producers (11). Two case studies (2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative and 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative) involved site visits to conduct in-person interviews; the remaining interviews were conducted by telephone. Table 1 above presents a breakdown of these interviews.

1.3 Methodological considerations

A number of factors influenced the extent to which the performance of the ADRP could be assessed. First, during the period covered by the evaluation, only three AgriRecovery initiatives had been approved under the GF2 policy framework, of which one had a completed final report.Footnote 3 This limited the ability to assess the intended outcomes of the ADRP following the changes to the AgriRecovery Framework; however, efforts were made to mitigate this limitation by conducting in-depth case studies of the two GF2 initiatives underway at the time of the evaluation, as well as by including information collected during the 2015-16 fiscal year related to the three initiatives undertaken under GF2.

Second, AgriRecovery initiatives require that the affected province or territory conduct surveys or use other adequate means to assess the impact of funding provided through AgriRecovery. Surveys of participating producers were not conducted for approximately one third of the AgriRecovery initiatives completed during the period covered by the evaluation. For those initiatives for which surveys were not completed, provinces submitted other information, including in some cases regional/sectoral intelligence, on the impact of the initiatives. The case studies analyzed the performance of individual AgriRecovery initiatives, but those findings are specific to each case and cannot be extrapolated to assess producer satisfaction with other initiatives. To mitigate this limitation, key informants were asked to provide their perceptions of overall producer satisfaction with the AgriRecovery Framework.

Finally, there are challenges to attributing producers’ ability to recover from disaster events directly to the contributions of the ADRP given the various factors. Two of these factors are financial assistance provided by other AAFC Business Risk Management (BRM) or federal/provincial programs to support disaster-affected producers and, external pressures influenced producers’ ability to recover at the individual level. Efforts were made as part of the case studies to assess the perceptions of producers and other stakeholders of the impact of AgriRecovery assistance specifically on their recovery, as well as to examine available data on the financial recovery of the relevant sectors. While it was not possible to quantify to what extent disaster recovery was attributable to AgriRecovery initiatives due to the various activities undertaken within a single disaster, it was possible to determine that AgriRecovery funding was one of the contributing factors to economic recovery following agricultural disaster.

2.0 Program profile

2.1 Program context

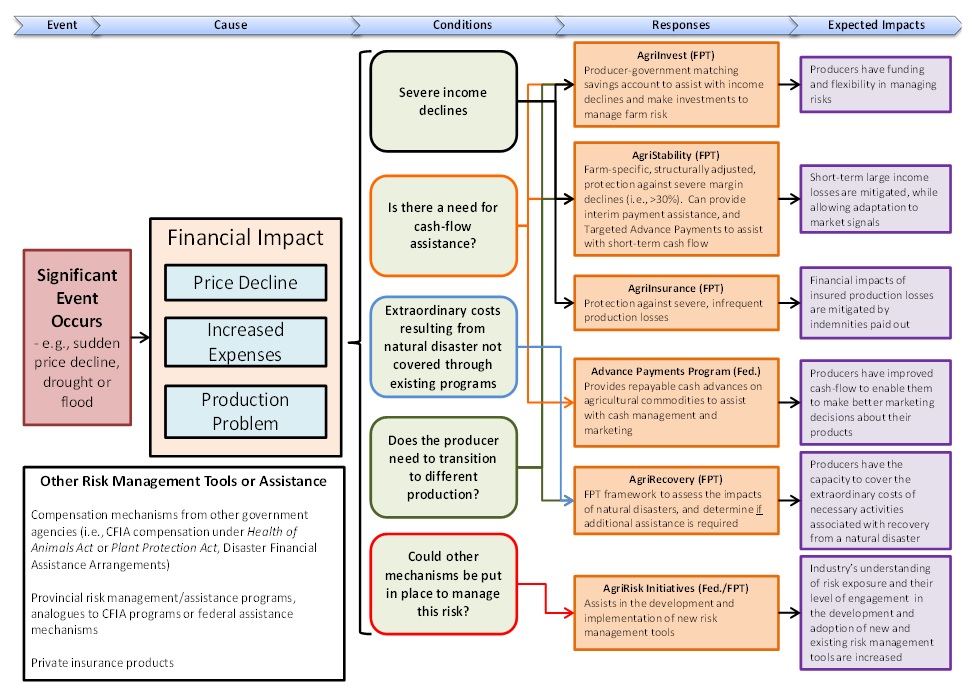

In 2006, the FPT governments agreed to implement the AgriRecovery Framework as a national agricultural disaster relief strategy. The federal share of the Framework is administered through the ADRP as part of AAFC’s BRM suite of programsFootnote 4 (see Annex B). BRM programs aim to protect producers’ income and share financial risks of events beyond their control such as low commodity prices, reduced production due to weather or disease, or increased input costs.

While other BRM programs are designed to address production and income losses, AgriRecovery initiatives, developed under the AgriRecovery Framework, are focused on helping producers with the extraordinary costs needed to recover from natural disasters, such as for the destruction of diseased animals or crops, replanting, or the purchase and transportation of animal feed. AgriRecovery initiatives are cost-shared on a 60:40 basis between the federal government and participating provinces or territories, and initiatives are typically delivered by the participating province/territory, or its delivery agent. The ADRP is the federal mechanism for administering the federal share of the AgriRecovery Framework.

Prior to the implementation of the AgriRecovery Framework in 2006, AAFC provided ad hoc disaster relief through initiatives designed in response to specific disaster events. This ad hoc approach led to inconsistencies in how initiatives were designed and administered, and impeded the ability of governments to provide disaster support that was both timely and effective. The FPT AgriRecovery Framework was intended to provide structure, clarity, and consistency to the decision-making process surrounding agricultural disaster relief, including cost-sharing arrangements for determining when and how FPT governments respond to a disaster.

2.2 Overview of the program

The ADRP provides the mechanism through which the federal government participates and funds specific initiatives developed under the AgriRecovery Framework. The objective of the ADRP is to provide a federal response to natural disaster events through joint FPT initiatives to assist affected producers with:

- the additional costs of activities necessary to resume business operations as quickly as possible; or,

- the additional cost of short-term actions necessary to mitigate and/or contain the impacts of the disaster on producers.Footnote 5

As part of the BRM program suite, the governance structure for the Framework consists of working groups and committees, including the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Business Risk Management (FPT BRM) Working Group and a Federal-Provincial-Territorial AgriRecovery Administrators Group, as well as the National Program Advisory Committee, which includes FPT government and sectoral representatives. These groups examine BRM policy and program issues and, when requested, develop options to be brought forward to FPT Assistant Deputy Ministers, Deputy Ministers and Ministers.

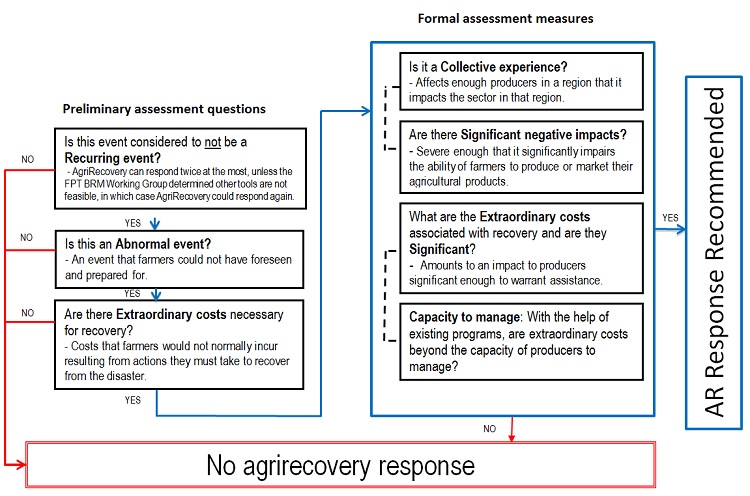

The AgriRecovery Framework is jointly administered by FPT governments and specifies how they will work together when a province or territory requests assistance in response to a natural disaster. Under the GF policy framework (2008-2013), the following four criteria had to be met to trigger a disaster response under the AgriRecovery Framework:

- the event was a collective experience;

- there were significant negative impacts;

- the event was not part of a cyclical or long-term trend; and,

- the costs or losses were beyond the capacity of individual producers to manage with the assistance of existing programming.

Under the GF2 policy framework in 2013, those criteria were refined and quantified and an additional criterion was added:

- there are extraordinary costs associated with recovery and they are significant.

This criterion was intended to clarify that AgriRecovery only provides assistance for the costs necessary for recovery beyond what is addressed through existing programs. In defining the role of AgriRecovery, the Framework also defines the roles of the other BRM programs: to address declines in production and income. Table 2 below outlines the AgriRecovery Framework assessment criteria under GF and GF2, demonstrating changes to the criteria between policy frameworks.

Table 2: AgriRecovery disaster assessment criteria under Growing Forward and Growing Forward 2

Growing Forward (2008-2013)

Federal-Provincial-Territorial Task team assessment following provincial request

- Is the event not considered to be cyclical or part of a long-term trend?

- Is it a collective experience?

- Are there significant negative impacts?

- Are the costs and losses beyond the capacity of individual producers to manage with the assistance of existing programming?

Growing Forward 2 (2013-2018)

Initial assessment conducted by the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program and impacted province/territory

- Is this event considered to not be a recurring event?

- AgriRecovery can respond twice at the most, unless the FPT BRM Working Group determined other tools are not feasible, in which case AgriRecovery could respond again.

- Is this an abnormal event?

- An event that farmers could not have foreseen and prepared for.

- Are there extraordinary costs necessary for recovery?

- Costs that farmers would not normally incur resulting from actions they must take to recover from the disaster.

Federal-Provincial-Territorial Task team assessment upon receipt of initial assessment

- Is it a collective experience?

- Affects enough producers in a region that it impacts the sector in that region.

- Are there significant negative impacts?

- Severe enough that it significantly impairs the ability of farmers to produce or market their agricultural products.

- What are the extraordinary costs associated with recovery and are they significant?

- Amounts to an impact to producers significant enough to warrant assistance.

- With the help of existing programs, are the extraordinary costs beyond the capacity of producers to manage?

A further change was made in the process for triggering an AgriRecovery response under GF2. Under GF, the formal FPT Task Team assessment was initiated when a provincial or territorial Minister sent a letter requesting assistance to his or her federal counterpart. Under GF2, the ADRP and impacted province/territory conduct a preliminary assessment of the disaster to determine whether there is a need for the FPT Task Team to undertake a formal assessment. For a formal assessment to occur, the preliminary assessment must establish that: the disaster was not a recurring event; it was an abnormal event; and there were extraordinary costs necessary for recovery.Footnote 6

The FPT Task Team’s formal assessment determines whether four additional criteria are met and, based on the outcome, provides options and recommendations for consideration by the federal and relevant provincial/territorial Ministers of Agriculture. Should the Ministers approve the AgriRecovery initiative, federal and provincial officials then develop, obtain authorities for, and FPT governments announce the initiative. Initiatives are cost-shared by a ratio of 60:40 between the federal government and the participating provincial/territorial government. Producer payments under the ADRP are typically delivered to producers by the province or its delivery agency, but may also be delivered directly by AAFC.

2.3 Program resources

The federal government provides an annual allotment of up to $125 million for AgriRecovery initiatives. Due to the unpredictable nature of agricultural disasters, it is not expected that this allotment will be spent every year. Since 2012, central agency approval is required for each AgriRecovery initiative funded under the Framework. Table 3 provides an overview of ADRP spending by fiscal year, which demonstrates the variability in annual spending on AgriRecovery initiatives (Statutory Grants and Contributions columns).

| Fiscal year | Vote 1 and employee benefit plans [A] | Federal payments to producers (Statutory Grants and Contributions) [B] |

Federal payments for delivery costs (Statutory Grants and Contributions) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

*Source: AgriRecovery actuals. Figures provided by AAFC Corporate Management Branch, October 21, 2015 ** The negative value in 2013-14 is due to an overpayment made in 2011-12 being refunded/ credited to the statutory fund over subsequent fiscal years. In 2013-14, the credit to adjust this overpayment exceeded the payments made that fiscal year. [A] Vote 1 and employee benefit plans actuals include salary, TB recoverables, non-pay operating and contributions to Employee Benefit Plans, but exclude accommodation. [B] The statutory grants and contributions from 2011-12 to 2014-15 reflect payments to producers and payments for delivery costs. The amounts are net of recoveries and include Payables at Year End net of writedowns. Payables at year end writedowns are netted against the year they were set up. |

||||

| 2011-2012 | 1,374,822 | 235,279,862 | 2,459,234 | 239,113,918 |

| 2012-2013 | 1,856,750 | 11,545,821 | 369,017 | 13,771,588 |

| 2013-2014 | 1,616,456 | 1,277,789 | (53,232)** | 2,841,013 |

| 2014-2015 | 992,782 | 3,231,972 | 135,964 | 4,360,718 |

| Total | 5,840,810 | 251,335,444 | 2,910,983 | 260,087,237 |

Table 4 details the ADRP grant and contribution expenditures, combined federal and provincial expenditures, and the number of payments made to producers, for all AgriRecovery initiatives approved in the period covered by the evaluation.

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward (April 2011 to March 2013) | Total federal spending ($) | Total federal and provincial spending ($) |

Number of payments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

*The totals in Table 4 include payments made up to the end of 2015-16, and so do not correspond to the totals in Table 3. The 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative and the 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative spending included payments made in 2015-16. **Note: NR, or Not Reported, appears for confidentiality reasons when 10 or fewer producers received payments. |

|||

| 2011 Canada-Saskatchewan Excess Moisture Program | 142,359,450 | 237,265,655 | 20,241 |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Excess Moisture Initiative II | 22,538,309 | 37,563,849 | 5,643 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Agricultural Recovery Program | 67,428,014 | 112,380,023 | 11,634 |

| 2011 Canada-Quebec Excess Moisture and Flooding Initiative | 51,888 | 86,480 | 107 |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Feed Assistance & Pasture Restoration Initiative | 793,456 | 1,322,427 | 470 |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Excess Moisture Initiative | 1,399,428 | 2,332,380 | 78 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | 133,031 | 221,718 | NR** |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Bovine Tuberculosis Assistance Initiative | 104,538 | 174,229 | NR** |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative | 1,176,228 | 1,960,380 | 11 |

| 2011 Canada-New Brunswick Excess Moisture Initiative | 4,906,080 | 8,176,799 | 146 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative | 7,103,453 | 11,839,084 | 1,514 |

| 2012 Canada-Quebec Drought Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiatives | 113,382 | 188,967 | 91 |

| 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiative | 222,844 | 480,958 | 63 |

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward 2 (April 2013 to March 2015) | Total federal spending ($) | Total federal and provincial spending ($) |

Number of payments |

|---|---|---|---|

| **Note: These initiatives did not have final reports at the time the evaluation was completed; the values in this table represent reported totals as of November 2015. | |||

| 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative | 756,254 | 1,260,423 | 41 |

| 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative** | 2,940,000 | 4,900,000 | 465 |

| 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative** | 405,152 | 675,254 | 14 |

3.0 Evaluation findings

This section presents key findings related to the relevance and performance of the ADRP, including its achievement of expected outcomes and the extent to which economy and efficiency have been realized.

3.1 Relevance

The assessment of the relevance of ADRP included an examination of its continued need and its alignment with federal priorities, AAFC's strategic outcomes, and federal roles and responsibilities.

3.1.1 Continued need for the program

The literature review, interviews and case studies provided evidence of an ongoing need for a disaster relief framework as part of a suite of programs to help agricultural producers manage their business risks. Research literature indicates that disasters will continue to occur unpredictably, and the literature points to an increasing frequency of these events in the future. The evaluation evidence indicates that there is a need for AgriRecovery specifically, in cases where other BRM, provincial/territorial, or private sector programs are not designed to cover the extraordinary costs included under the Framework to assist producers in recovering from disaster events. The evaluation found that the AgriRecovery Framework meets this continued need more effectively and equitably than would ad hoc programming.

Literature reviewed as part of the 2011 Evaluation of the ADRP demonstrated that agricultural producers face risks from severe weather events and disease outbreaks that are not predictable.Footnote 7 Literature published since then provided evidence that over the longer term, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are expected to increase. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported there is medium confidence that droughts will intensify in the 21st century in some seasons and areas, due to reduced precipitation and increased evapotranspiration, including over central North America.Footnote 8 A 2013 report from Simon Fraser University foresees an increase in the duration and severity of extreme weather events that could result in severe impacts on producers such as those experienced following the 2011 Manitoba floods.Footnote 9

LiteratureFootnote 10, as well as interviews and case studies conducted as part of this evaluation, provided evidence that agricultural disasters impose recovery costs that are not covered or are not covered in a timely manner by other BRM programs, nor by provincial programs or private sector mechanisms. According to literature reviewed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), there is general consensus that some types of catastrophic risks, such as those posed by disaster events, cannot be managed by individual private actions or insurance markets.Footnote 11 Key informants indicated that disasters give rise to extraordinary costs that must be addressed more quickly than is feasible for other BRM programs.

The literature demonstrated that the need for agricultural disaster relief was recognized internationally. Most OECD member countries provide some form of disaster assistance to their agricultural sectors. In Australia, two programs provide ad hoc support to recover from drought and other types of catastrophic climate events.Footnote 12 In the United States, four specialized disaster programs provide assistance for livestock and tree fruit producers under the 2014 Farm Bill.Footnote 13 Almost all European Union member states provide ad hoc agricultural disaster recovery payments, with a small percentage having either public or private stabilization funds in place.Footnote 14

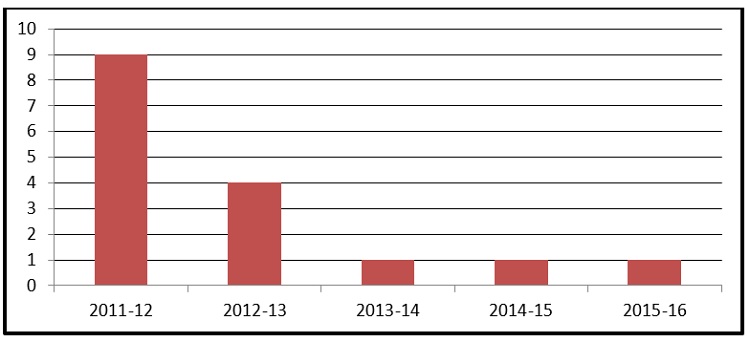

The need for agricultural disaster assistance is also demonstrated through the uptake of AgriRecovery assistance. From the first AgriRecovery initiative in 2007 to the time of this evaluation, there were 53 requests for disaster assistance that led to 41 initiatives funded under the AgriRecovery Framework. During the period covered by the evaluation, 16 AgriRecovery initiatives were undertaken, including 13 under GF and three under GF2. During that period, an additional five assessments resulted in a determination that AgriRecovery criteria for assistance had not been met. Figure 1 below shows the number of AgriRecovery initiatives approved in each of the fiscal years covered by the evaluation. While Figure 1 demonstrates a relatively low number of AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken in the three fiscal years following 2011-12, key informants believe this is due to the unpredictable nature of agricultural disaster events rather than a decline in need. This view is supported by literature on the nature of agricultural disaster events.

Description - Figure 1

- 2011-12: Nine initiatives funded during the period covered by this evaluation.

- 2012-13: Four initiatives funded during the period covered by this evaluation.

- 2013-14: One initiative funded during the period covered by this evaluation.

- 2014-15: One initiative funded during the period covered by this evaluation.

- 2015-16: One initiative funded during the period covered by this evaluation.

Benefits of a disaster assistance framework

Prior to the development of the AgriRecovery Framework, agricultural disaster relief was provided on an ad hoc basis by AAFC and the provinces and territories. Evidence from the literature and interviews highlighted the advantages of having a framework to facilitate the response by governments to agricultural disasters. Studies from the OECD have demonstrated that governments are better prepared to provide disaster assistance if they establish a framework in advance that defines criteria for determining whether, and what types of, assistance will be provided. Outlining the responsibilities of governments prior to disaster events occurring can reduce political pressure, simplify decision-making processes, and lower uncertainty associated with budgetary costs.Footnote 15

Federal and provincial officials interviewed as part of the evaluation stated that the AgriRecovery Framework has demonstrated these advantages in practice. Without the Framework, they said there would be pressure for AAFC to provide ad hoc assistance and that as a result, initiatives would likely be more costly and less coordinated than those undertaken through the AgriRecovery Framework.

Many key informants noted that the AgriRecovery Framework contributes to a more fair and consistent response at the national level, since the same assessment criteria are applied across all provinces, territories and sectors. Many key informants noted that the assessment process contributes to ensuring producers and sectors receive assistance based on need, rather than on their ability to apply pressure for assistance. For example, several stakeholders interviewed on the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative indicated that without the AgriRecovery Framework in place, the Nova Scotia strawberry sector, being a small sector in a small province, might not have received federal assistance. One key informant noted that the voice of the sector might not have been "loud enough to resonate" at the federal level if it had to seek ad hoc funding.

Overall, evaluation evidence demonstrated a continued need for the ADRP and AgriRecovery initiatives.

3.1.2 Alignment with federal priorities and departmental strategic outcomes

A review of Government of Canada and AAFC policy documents, as well as key informant interviews with federal officials conducted as part of the evaluation, demonstrated the ADRP's alignment with both federal priorities and AAFC strategic outcomes.

The 2006 Speech from the Throne included a federal commitment to "create separate and more effective farm income stabilization and disaster relief programs and to work with producers and partners to achieve long-term competitiveness and sustainability [of the sector]".Footnote 16 The Government's commitment to supporting innovation, competitiveness and market development in the agriculture sector was reasserted in Budget 2013, which provided $3 billion in funding for a renewed FPT agricultural policy framework under GF2, as well as ongoing funding for BRM programming. The AgriRecovery Framework forms a key component of that policy framework and supports the goal of helping farmers in managing risks arising from severe market volatility and disaster situations.

AAFC's 2014-2017 Business Plan notes that the ADRP and AgriRecovery Framework contribute to the department's core mandate. Specifically, AgriRecovery provides assistance to support risk management and a return to profitability and competitiveness for agricultural businesses impacted by disaster. The AgriRecovery Framework is part of the BRM suite of AAFC programs that support the end outcome of "mitigating financial risk and the impact of natural disasters while still allowing for adaptation to market signals", as well as the departmental Strategic Outcome of a "competitive and market-oriented agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products sector that proactively manages risk".Footnote 17

Overlaps or gaps with other Business Risk Management programs

In 2011, an OECD study cautioned that the Canadian agricultural risk management system was overcrowded and unable to signal risks for which farmers should take responsibility for managing.Footnote 18 The study recommended stricter assessment criteria for AgriRecovery assistance and a clear definition of the risks to be covered by the program. Evidence gathered as part of this evaluation found that these recommendations had been addressed through refinements to the AgriRecovery Framework and the other programs in the BRM suite under GF2.

Evidence from the interviews, case studies, and file and document review demonstrated that the ADRP aligns with and complements other BRM programsFootnote 19 by filling what would otherwise be a gap in disaster assistance for producers. AgriRecovery's niche is in helping producers cover the extraordinary costs of activities necessary for recovery from a natural disaster. Most federal and provincial representatives interviewed believe there is little or no overlap between AgriRecovery and other BRM programs. These representatives further stated that the refinement of AgriRecovery criteria under GF2has improved the program's ability to avoid such overlap. With the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative initiated under GF2, stakeholders saw no overlap with other BRM programs due to its focus on covering the extraordinary costs of the destruction and replanting of strawberry plants.

Other BRM programs, particularly AgriStability and AgriInsurance, are intended to assist producers in managing the risks of agricultural disaster events; the AgriRecovery Framework is designed to cover costs beyond the capacity of producers to pay with the assistance of other BRM programs. In many cases, the financial support disaster-affected producers would receive from AgriStability would not be provided in time to cover the costs associated with disaster recovery activities. When that is the case, the AgriRecovery Framework allows producers to access funding earlier than would be possible through AgriStability. Federal officials interviewed as part of the evaluation noted that those AgriRecovery payments are then taken into account in AgriStability margins, to avoid duplication of payments. This observation is supported by information in ADRP files: when calculating which costs should be covered through AgriRecovery initiatives, assessments consistently took into account the assistance available to producers through other BRM programs or other sources to avoid duplication.

Evidence from the case studies showed that AgriRecovery initiatives effectively filled gaps in assistance to producers. For example, in the 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative, the case study showed that no other programs were available to compensate producers for the significant costs of destroying birds, cleaning and disinfecting barns, and replacing the birds.

Overall, the evaluation found that the AgriRecovery Framework complements other BRM programs, and key informants did not believe there was overlap between the Framework and other federal or provincial programs.

3.1.3 Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

Evidence from the document review, interviews and case studies indicated the AgriRecovery Framework and ADRP fulfill an important federal role by providing an effective mechanism to address agricultural disasters at the national level.

Section 95 of the Constitution Act defines agriculture as a shared federal-provincial responsibility. Further, Section 12 of the Farm Income Protection Act gives the Minister of Agriculture the authority to work with the provinces to respond to exceptional circumstances not covered under the agricultural income stabilization and insurance programs authorized by the same Act. This forms the legislative basis for the establishment of the AgriRecovery Framework, including the federal share which is administered by the ADRP. Therefore, the ADRP fully aligns with the federal role.

The ADRP and the AgriRecovery Framework are also the means through which the federal government ensures equitable agriculture disaster assistance across jurisdictions. Several key informant interviewees expressed a similar view in that the federal government has a responsibility to provide consistent and equitable support to producers and sectors across provinces and territories. Provincial representatives interviewed as part of the evaluation said that AgriRecovery and its 60:40 federal-provincial cost sharing provision, a ratio consistent with other BRM programs, play an important role in ensuring there is financial capacity to address agricultural disaster recovery in all provinces and territories.

There is also evidence of federal responsibility to assist in disaster situations generally. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency also has the legislative authority to provide financial assistance under the Plant Protection Act and Health of Animals Act in response to disasters such as disease and pest outbreaks. Beyond the agriculture sector, Public Safety Canada plays a national role in responding to provincial requests for disaster assistance through its Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements. The Department of National Defence and Canadian Forces are called on to respond as required.

3.2 Performance

The effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the ADRP were assessed in order to evaluate its performance. The assessment of effectiveness focused on the achievement of outputs and outcomes as set out in the ADRP's Program Performance Measurement and Risk Management Strategy (PPMRMS). The evaluation found that the program has achieved its immediate and progressing towards achieving its intermediate outcomes, as well as having contributed to the performance of the BRM program suite more broadly. With respect to efficiency and economy, the evaluation evidence indicates that the AgriRecovery Framework is an efficient and economical alternative to ad hoc disaster relief programming, and the costs to administer the Framework federally through the ADRP are reasonable.

The evaluation also includes a review of program design and delivery, including the achievement of related performance measure targets. The program design and timeliness have improved under GF2, though some areas for improvement remain.

3.2.1 Program design and delivery

This section examines the effectiveness of the ADRP program design and delivery methods. As discussed, given the earlier assessments of the program under GF, this evaluation focuses on the changes to the program under GF2, their implementation, and, where possible, the impacts of those changes.

3.2.1.1 AgriRecovery assessment criteria

Overall, producer association and federal and provincial representatives interviewed as part of the evaluation found the AgriRecovery Framework criteria in place under GF2 to be fair and reasonable. As described in Section 2.2 and Table 2 above, under GF, four main criteria were developed for FPT Task Teams to assess whether an AgriRecovery response should be triggered.

Two major challenges were identified with the assessment process under GF. First, as indicated in the 2011 Evaluation of the ADRP, the FPT Task Teams conducting AgriRecovery assessments lacked clear, quantitative definitions for some of the criteria, which created pressure to respond to events that did not fall within the AgriRecovery Framework's disaster criteria.

Second, following ADRP payments exceeding the $125 million annual federal funding allotment for the program in 2010-11 and 2011-12, steps were taken to make AgriRecovery more focused and fiscally responsible. AAFC worked with the provinces and territories, through the FPT BRM Working Group, to complete a review of the Framework in 2013, and FPT governments agreed to refined AgriRecovery criteria under GF2 as part of a revised set of FPT AgriRecovery Guidelines.

An important change to the Framework was to focus AgriRecovery on covering only the extraordinary costs necessary for producers to recover from a disaster, with production and income losses to be addressed through other BRM programs. Further, to trigger an AgriRecovery response, those extraordinary costs had to represent a significant portion of producers' average gross revenue and be beyond the financial capacity of producers to manage, taking into account the assistance available through other programs.

The refined criteria also limit the number of times AgriRecovery can respond to recurring disaster events. Under GF2, AgriRecovery can only respond to the same event twice, unless it is determined that other tools cannot feasibly be used, or that they are under development. The Framework also clarified that AgriRecovery can only respond to abnormal events that are beyond a set probability of occurrence. These are in addition to the requirements for an eligible disaster to be a collective experience, affecting a significant portion of a sector within a defined region, and that the disaster resulted in, or has the potential to result in, a significant negative impact on the ability of affected producers to carry out their farming activities.

Finally, under GF2, the assessment process is undertaken in two parts. Upon request from a province or territory, the ADRP and impacted province/territory conduct a preliminary assessment of the disaster to determine whether there is a need for the FPT Task Team to undertake a formal assessment. For a formal assessment to occur, the preliminary assessment must establish that: the disaster was not a recurring event; it was an abnormal event; and there were extraordinary costs necessary for recovery. If these criteria are met, a more thorough formal assessment is conducted to determine whether there may be need for an AgriRecovery response.

The ADRP undertook a number of outreach activities to communicate the changes in AgriRecovery assessments to industry associations, including publishing an AgriRecovery Guide on the AAFC website and making presentations to six major national commodity organizations.

Case studies examining two of the AgriRecovery initiatives implemented under GF2 assessed stakeholder perceptions on the appropriateness of the refined assessment criteria and their application. Stakeholders interviewed as part of the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative case study indicated that the AgriRecovery assessment criteria were appropriate and accurately assessed the events in question as disasters.

In the case of the 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative there was general agreement among stakeholders interviewed that the criteria were fair. However, questions were raised about whether the criteria were applied appropriately. Given that AgriRecovery had previously responded to excess moisture events affecting Manitoba livestock producers in 2008, 2010 and 2011, some questioned whether the 2014 flooding represented a recurring event. The AgriRecovery guidelines provide some flexibility as to when and the type of insurance products that could be developed. While Manitoba made certain improvements to their insurance coverage, these improvements did not lead to increased participation in insurance and highlighted additional work necessary to provide producers an effective product, and as a result, the event was not considered to be recurring. Of note, while Manitoba requested an AgriRecovery response in 2014, Saskatchewan did not make a similar request; while the province did experience flooding, the Saskatchewan government indicated that the impacts of the flooding within their province were different than those experienced in Manitoba and did not warrant a request for federal assistance.

The initiative's forage assistance was provided to producers in the Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipegosis regions impacted by rising lake levels, and the related multi-year impacts. Although this could be considered a recurring initiative under the Framework's criteria, existing insurance products did not cover producers in those regions.

Despite the questions raised above, evaluation evidence indicates that the refined AgriRecovery assessment criteria were appropriate and represented an improvement to program design.

3.2.1.2 Agricultural Disaster Relief Program performance measurement

Following the renewal of the AgriRecovery Framework under GF2, the ADRP updated its PPMRMS in November 2014, including a new Performance Measurement Strategy. Evidence from key informant interviews and the document and file review indicated that the 2014 PPMRMS adjusted the ADRP's performance measures to better assess how initiatives are delivered. However, the ADRP should ensure that the final reports on AgriRecovery initiatives submitted by the affected province or territory include performance data collected once initiatives are completed in order to obtain a full picture of program results. They could use, for example, producer surveys, contact with industry representatives, or analysis of producers' financial situation, as appropriate to assess the impact of AgriRecovery assistance. Of the 14 AgriRecovery initiatives reviewed as part of this evaluation for which final reports had been submitted, five, or 36 per cent, did not use producer survey results to assess the impact of AgriRecovery assistance on recipients, though the reports provided regional/sectoral intelligence on the impact of the initiatives, based on information obtained through other means such as contact with the industry.Footnote 20

Following recommendations arising from the 2011 Evaluation of the ADRP by the OAE and the 2013 OAG audit, AAFC introduced the BRM Cost-Sharing System, an online FPT financial and reporting system that allows AAFC to set and track milestones throughout the AgriRecovery process. The ADRP began using the new system under GF2 in April 2013. According to program staff, the new system, in addition to standardized assessment and agreement templates, has reduced the time taken for the administration of AgriRecovery initiatives. Several provincial representatives spoke positively about the ease of submitting information through the new system. However, one provincial representative found the frequency of reporting unnecessarily onerous, given the low materiality of the initiative in question.

While the ADRP should ensure that all final reports for AgriRecovery initiatives include data on the impact of the initiative on producers' ability to recover from disaster, refinements to the program's PPMRMS and the creation of the BRM Cost-Sharing System represent improvements to the ADRP's performance measurement capacity.

3.2.1.3 Timeliness

AgriRecovery initiatives implemented under GF2 to date have met their initial output targets with respect to timeliness, though challenges to the delivery of timely assistance remain. The AgriRecovery Framework was put in place to "speed up the delivery of assistance to producers affected by disaster events so that they can recover as quickly as possible"Footnote 21, compared to the delivery of ad hoc assistance.

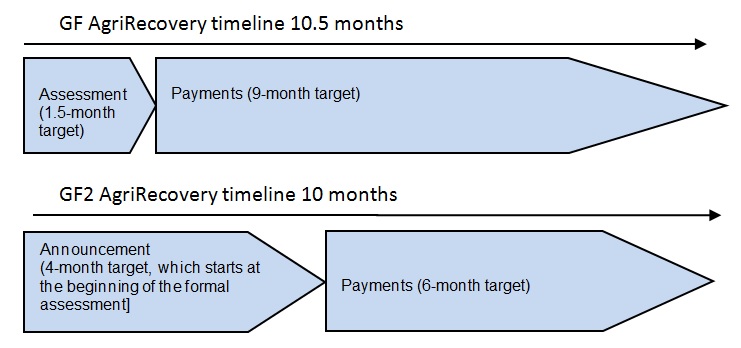

Under GF, the ADRP had a target of 10.5 months for the delivery of AgriRecovery initiatives from the time a request was made: 1.5 months for completing an AgriRecovery assessment and a further nine months for delivering 75 per cent of payments to producers.

Under GF2, the ADRP has a 10-month target for its AgriRecovery initiatives from the time the initial assessment is completed by the ADRP and the impacted province or territory. Once a formal AgriRecovery assessment is initiated, AAFC and the province/territory have four months in which to inform producers whether an AgriRecovery initiative will be put in place and a further six months to deliver 75 per cent of payments to producers. Figure 2 presents a summary of the timeliness indicators for the ADRP, showing the changes between GF and GF2.

Description - Figure 2

- GF AgriRecovery timeline for 10.5 months:

- Assessment is conducted within 1.5 month target

- Payments are made over a 9-month target

- GF2 AgriRecovery timeline for 10 months:

- Announcement is conducted for 4 months, which starts at the beginning of the formal assessment

- Payments are made over a 6 month target

The performance target for having 75 per cent of initiative payments to producers has been reduced to 10 months under GF2, from 10.5 months under GF. However, the timeline now begins with the completion of the preliminary assessment and the start of the formal assessment process. Under GF, timelines included initial assessment of the disaster.

Evidence from the case studies indicated producers require timely information on whether they will be receiving assistance through AgriRecovery in order to make business decisions related to recovery activities. Many of the producers and producer association representatives interviewed noted the crucial element for timely disaster recovery is having the knowledge that assistance will be provided. With that knowledge, producers can cash-manage until the assistance arrives. For four of the six AgriRecovery assessments reviewed as part of the case studies, producers and producer representatives found information was communicated to them, either formally or through informal channels, on the availability of assistance within the timeframes required for them to make business decisions.

Timeliness under Growing Forward

Of the 13 AgriRecovery initiatives approved under GF during the period covered by the evaluation, 15 per cent met the performance target for completing an the AgriRecovery assessment within 1.5 months and 54 per cent met the 10.5 month target for the delivery of 75 per cent of payments to producers. According to the 2013 OAG report, while the AgriRecovery initiatives affecting the largest numbers of producers with the highest dollar values were generally delivered within the targeted timelines, smaller responses more often failed to meet their timeliness targets. Table 5 below presents a list of these 13 initiatives and indicates which met their timeliness targets.

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward (April 2011 to March 2013) | AgriRecovery assessment completed in 1.5 months | 75% of payments made in 10.5 months |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 Canada-Saskatchewan Excess Moisture Program | Not met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Excess Moisture Initiative II | Met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Agricultural Recovery Program | Met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-Quebec Excess Moisture and Flooding Initiative | Not met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Feed Assistance and Pasture Restoration Initiative | Not met | Not met |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Excess Moisture Initiative | Not met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | Not met | Not met |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Bovine Tuberculosis Assistance Initiative | Not met | Not met |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative | Not met | Not met |

| 2011 Canada-New Brunswick Excess Moisture Initiative | Not met | Met |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative | Not met | Met |

| 2012 Canada-Quebec Drought Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiatives | Not met | Not met |

| 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiative | Not met | Not met |

Many of the provincial and federal officials interviewed said that delays in adhering to AgriRecovery assessment timelines were partly due to the time needed to collect comprehensive information on the impact of an event on producers. In the case of weather-related disasters involving crops, it was not possible to calculate the losses incurred by producers until harvesting was completed. Some key informants noted that, with respect to the immediate aftermath of disease-related disasters they had observed, producers were often too busy undertaking urgent recovery activities to provide government officials with the information required for an assessment until those activities were completed or well underway. These constraints contributed to formalizing the requirement under GF2 that a preliminary assessment be conducted, allowing the formal assessment to proceed only once relevant information is available.

Timeliness under Growing Forward 2

All three AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken under GF2 during the period covered by the evaluation were announced within the 120-day target outlined in the ADRP's updated PPMRMS. However, producers involved in two of those initiatives indicated that announcements were made too late for them to make relevant business decisions.

For the three AgriRecovery initiatives completed under GF2 during the period covered by the evaluation, AAFC met its target for the delivery of 75 per cent of payments within 10 months for two of the initiatives. The target was not met for the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative. Provincial officials in Nova Scotia noted the ADRP's 10-month target for delivery of 75 per cent of payments did not align with the initiative's design, which required most producers to undertake recovery activities across two growing seasons, a process that took longer than 10 months from the request for assistance. Producers interviewed as part of that case study indicated they received their payments in a timely manner.

Table 6 below presents a list of AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken under GF2 to March 2015, and indicates which met the updated timeliness targets.

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward 2 (April 2013 to March 2015) | Announcement of assistance made in 4 months | 75% of payments made within 10 months |

|---|---|---|

|

* Note: Progress reports submitted by Manitoba show that payments under the 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative were completed by July 2, 2015, in advance of the July 20, 2015 target. ** Note: Progress reports submitted by British Columbia show that payments under the 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative were completed in July 2015, in advance of the November 5, 2015 target. |

||

| 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative | Met | Not met |

| 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative | Met | Met* |

| 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | Met | Met** |

Findings indicated that administrative challenges to the timely delivery of AgriRecovery initiatives remain. In interviews, provincial and federal officials emphasized that the primary goals of the AgriRecovery Framework present competing pressures on the ADRP: to provide timely assistance to producers recovering from disaster, while ensuring that the assistance being provided covers only extraordinary costs and does not overlap with other assistance. One official stated: "Delays arise from trying to get better data to inform decision-making, determining whether there is a rationale for an initiative, seeing what losses were incurred, determining how other BRM programs responded, and coming together with the province. When an assessment takes a long time, it's usually because FPT officials are trying to answer the assessment questions and follow the process." These findings indicate that each disaster assessed under the Framework presents unique challenges, scopes, risks, complexities, and circumstances, making a consistent timeframe for all assessments impossible.

A further challenge to timely delivery of assistance to producers is the current approvals process for AgriRecovery initiatives. Prior to 2010-11, the ADRP could seek Treasury Board approval for AgriRecovery initiatives within its $125 million annual allotment, up to $20 million per initiative. Since the program exceeded its allotment in 2010-11 and 2011-12, the ADRP must obtain approvals from central agencies for all AgriRecovery initiatives, regardless of materiality. Additionally, the respective provincial or territorial government must also seek approval of the initiative prior to implementation.Footnote 23 Many of the federal and provincial officials interviewed stated that current federal approval processes have slowed the announcement and delivery of initiatives.

Timeliness data from the three AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken under GF2 at the time of the evaluation, findings from the BRM Cost-Sharing System, ADRP files, and key informant interviews suggested that timeliness has improved under GF2.

3.2.1.4 Risk-based program delivery

As described in Section 3.2.1.3 (Timeliness) above, the evaluation found that smaller-scale AgriRecovery initiatives were less likely to meet timeliness targets than larger initiatives. Federal and provincial officials noted this was often due to the challenges in assessing whether smaller, more localized events met the assessment criteria for disaster assistance. With respect to the challenges of assessing smaller-scale possible disasters in a timely manner, the 2013 OAG report recommended that the ADRP adopt a risk-based process for streamlining administrative efforts for smaller, lower-value initiatives. The FPT governments have subsequently agreed on a risk-based approach to disaster assessments and initiatives intended to better balance the competing needs for timeliness of assistance delivery and the administrative processes and effort necessary to ensure assistance is targeted to the extraordinary costs of disaster recovery. This approach takes into consideration common risks and challenges related to the AgriRecovery assessment process, including: the urgency of notifying producers of assessment results; the complexity of the event in question; the availability of data related to the event; and the potential costs of a disaster response.

In May 2015, the FPT Assistant Deputy Ministers approved a two-stage process for rating initiatives as low, medium or high risk based on the risks and challenges identified above. Using a risk review template, a pre-assessment risk review phase is to be conducted shortly after a request for assistance is made, to ensure resources are applied to the key areas of concerns for the assessment. The second phase is to be conducted prior to completing the formal assessment, to ensure a common understanding of the key risks and to highlight any risk mitigation measures in the AgriRecovery response. This risk-based approach was not in use during the period covered by the evaluation.

3.2.1.5 Producer reporting requirements

The parameters for AgriRecovery initiatives, including application processes and producer reporting requirements, are determined separately for each initiative. As part of the efforts undertaken in the period covered by the evaluation to ensure AgriRecovery assistance covers only necessary recovery activities, AAFC and the participating provinces have developed initiatives requiring applicants to provide detailed farm-level information, including in many cases submission of receipts for expenses incurred on recovery activities. This change followed the refinements made to the AgriRecovery Guidelines in 2013, intended to better define the role of the Framework in focussing on the extraordinary costs pertaining to a producer's recovery. This enhancement was triggered by concerns that large disaster recovery initiatives under GF, such as the 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative, went beyond recovery assistance by including coverage of losses incurred by producers. Under GF2, the AgriRecovery criteria shifted to reimbursement of eligible producer costs incurred over the course of recovery activities, in an attempt to address concern that producer need, as determined through the assessment process, may be overstated in some cases.

Key informant responses were mixed as to the implementation of the receipt-based application process. Findings on the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative indicated the receipt-based process worked well. However, key informants interviewed about the 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiative considered that while the verification ensured that payments only went to producers who had undertaken necessary recovery activities, the receipt-based design slowed the delivery of assistance to producers. Provincial officials who had administered that initiative noted they often had to follow up with producers several times to obtain required documentation.

3.2.2 Achievement of expected outcomes

The extent to which the ADRP has achieved its expected outcomes was assessed in this evaluation through the document and file review, key informant interviews, and case studies. It was found that the program to a great extent achieved its immediate outcome of disaster-affected producers have the capacity to cover their extraordinary costs of recovery and are undertaking the necessary recovery activities. While it was too early to fully assess the longer-term results of the AgriRecovery initiatives implemented under GF2, evidence suggests that the ADRP is making progress toward the achievement of its intermediate outcome of disaster-affected producers resume business operations and/or mitigate the impacts of the disaster as quickly as possible. It was also determined that a positive outcome of the work of the ADRP, beyond those indicated in the program's logic modelFootnote 24, has been its contributions to improving other business risk management programs for producers.

3.2.2.1 Immediate outcome

Evidence indicates the ADRP has achieved its immediate outcome of ensuring that disaster-affected producers have the capacity to cover their extraordinary costs and to undertake necessary recovery activities. Participation targets for AgriRecovery initiatives have been met and evidence suggests that participating producers undertook the necessary recovery activities.

The performance indicator for the immediate outcome of the ADRP is the percentage of AgriRecovery initiatives in which at least 70 per cent of impacted producers or units of production participated in an AgriRecovery initiativeFootnote 25, with a program-level target of 70 per cent of initiatives meeting the expected participation rate. Program data from the period covered by the evaluation demonstrated the ADRP exceeded this target: 81 per cent, or 13 of the 16 AgriRecovery initiatives approved during this time met their participation targets. Table 7 below presents a breakdown of participation rates for each of these initiatives.

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward (April 2011 to March 2013) | Percent of producers affected by disaster applying for assistance (Target 80%*) |

|---|---|

| *The participation target under GF was 80% of affected producers apply for assistance once a disaster is designated. This target was revised to 70% under GF2. | |

| 2011 Canada-Saskatchewan Excess Moisture Program | 80 |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Excess Moisture Initiative II | 90 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Agricultural Recovery Program | 81 |

| 2011 Canada-Quebec Excess Moisture and Flooding Initiative | 85 |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Feed Assistance and Pasture Restoration Initiative | 59 (target not met) |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Excess Moisture Initiative | 92 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | 100 |

| 2011 Canada- British Columbia Bovine Tuberculosis Assistance Initiative | 100 |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative | 90 |

| 2011 Canada-New Brunswick Excess Moisture Initiative | 83 |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative | 91 |

| 2012 Canada-Quebec Drought Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiatives | 25 (target not met) |

| 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiative | 27 (target not met) |

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward 2 (April 2013 to March 2015) | Percent of producers affected by disaster applying for assistance (Target 70%) |

|---|---|

| 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative | 80 |

| 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative | 81 |

| 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | 100 |

The three AgriRecovery initiatives approved under GF2 at the time of the evaluation exceeded the performance target of 70 per cent of affected producers participating in the initiative. Findings from the case study indicated that, with regard to the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative, both producers and provincial officials indicated a much higher rate of completion of necessary recovery activities was achieved than would have been without the AgriRecovery initiative. Many key informants noted that providing an incentive to producers to take the necessary steps to eradicate the strawberry virus complex benefitted all producers, by reducing further transmission of the virus complex across the province.

The three AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken within the evaluation period that did not meet their participation targets, all approved under GF, were designed to assist livestock producers with forage shortfalls by providing assistance for the purchase or transportation of animal feed. According to federal and provincial key informants, the assessments had overestimated producers’ need for transporting purchased forage long distances.

The case studies provided in-depth information on the extent to which producers had undertaken all necessary recovery activities as part of AgriRecovery initiatives implemented during the period covered by this evaluation.

Evidence from the forage case study indicated that for the forage-related AgriRecovery initiatives reviewed, producers had the capacity to undertake the necessary recovery activities following initiatives payments. However, in the case of the 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative undertaken under GF,some key informants noted that it was not clear whether the funds available through the initiative were needed to ensure this capacity. Under this initiative, more than 1,500 payments were provided to producers for forage purchase and transportation assistance, due to a local forage shortfall. Of those payments, approximately half included claims for feed transport assistance. Some key informants suggested the low uptake of transportation assistance indicated local forage shortfalls were not as great as assessed at the outset of the disaster event, while others noted the discrepancy could indicate the assessment did not take into consideration alternative ways in which producers could minimize the impacts of the disaster. For subsequent forage-related initiatives examined as part of the case study, AgriRecovery payments were made following submission of receipts demonstrating that producers had undertaken the necessary activities; in these cases, it was clear that the initiatives contributed to producers’ recovery.

In the case of the 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative, 91 per cent of affected producers received AgriRecovery assistance. The initiative was designed such that assistance was only provided once producers submitted evidence that they had undertaken the necessary recovery activities: destruction of the impacted birds; cleaning and disinfection; and replacement of the birds. The design of the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative also ensured that all producers receiving AgriRecovery assistance had completed the necessary recovery activities. In that case, reimbursement was only available to producers once they provided evidence that both the plow-down and replanting had taken place. This procedure was followed in order to prevent producers from undertaking some, but not all, of the necessary recovery activities.

Overall, performance measurement targets for the ADRP’s immediate outcome were met and evidence suggested that AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken during the period covered by the evaluation ensured that disaster-affected producers had the capacity to cover extraordinary costs and undertake recovery activities.

3.2.2.2 Intermediate outcome

While it was too early to fully assess the intermediate results of several AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken during the period covered by the evaluation, evidence showed that the ADRP is making progress toward the achievement of its intermediate outcome of disaster-affected producers resuming business operations and/or mitigating the impacts of the disaster as quickly as possible. Evidence from the case studies indicated that for three-quarters of the completed initiatives reviewed, producers indicated the initiative had a significant positive impact on their ability to recover from a disaster event.Footnote 26

A challenge to assessing the achievement of this outcome was incomplete performance reporting on some initiatives. The performance indicator and target for the ADRP’s intermediate outcome, that 75 per cent of AgriRecovery recipients would indicate AgriRecovery payments played a role in their recovery from a disaster, was intended to be assessed through producer survey results or equivalent information. Of the 14 initiatives implemented in the period covered by this evaluation for which a final report had been completed, five reports did not include such information. Initiative final reports indicated the ADRP achieved its target in 46 per cent, or six of 13, initiatives delivered under GF. Further, the ADRP met its secondary target of 70 per cent of recipients still farming one year after the disaster payment in all of the initiatives for which data were available. Of the three initiatives approved under GF2 in the period covered by the evaluation, a final report had been received for one: the 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative. Data from that report indicated the initiative had played an important role in the recovery for well over 80 per cent of recipients, though that figure was determined by the number of producers who carried out all necessary recovery activities as outlined in the initiative, rather than being obtained through data collected following completion of the initiative. Table 8 below presents results against intermediate outcome indicators, for all AgriRecovery initiatives undertaken during the period covered by the evaluation.

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward (April 2011 to March 2013) | Percentage of recipients where AgriRecovery played a role in their recovery (Target 75%) |

Percentage of recipients still farming one year after disaster payment (Target 70%) |

|---|---|---|

|

* For this survey, 50% of respondents said AgriRecovery had a moderate to high impact on their recovery, while 50% said it had a low impact. ** Of the 470 participants, 332 participated in a survey and 330 of those were still in business one year following the receipt of the payment. |

||

| 2011 Canada-Saskatchewan Excess Moisture Program | No data available | >90% |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Excess Moisture Initiative II | 67% (target not met) | 99% |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Agricultural Recovery Program | No data available | No data available |

| 2011 Canada-Quebec Excess Moisture and Flooding Initiative | 100%* | No data available |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Feed Assistance and Pasture Restoration Initiative | 90% | >70%** |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Excess Moisture Initiative | 89% | 99% |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | 100% | 100% |

| 2011 Canada-British Columbia Bovine Tuberculosis Assistance Initiative | 100% | 100% |

| 2011 Canada-Alberta Salmonella Enteritidis Initiative | 78% | 100% |

| 2011 Canada-New Brunswick Excess Moisture Initiative | No data available | 96% |

| 2011 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Restoration Assistance Initiative | No data available | No data available |

| 2012 Canada-Quebec Drought Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiatives | 60% (target not met) | 100% |

| 2012 Canada-Ontario Forage and Livestock Transportation Assistance Initiative | No data available | No data available |

| AgriRecovery initiatives approved under Growing Forward 2 (April 2013 to March 2015) | Percentage of recipients where AgriRecovery played an important role in their recovery (Target 75%) |

Indicator not used under Growing Forward 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 Canada-Nova Scotia Strawberry Assistance Initiative | 95% | N/A |

| 2014 Canada-Manitoba Forage Shortfall and Transportation Assistance Initiative | Final report to be completed by March 31, 2016 | N/A |

| 2014 Canada-British Columbia Avian Influenza Assistance Initiative | Final report to be completed by March 31, 2016 | N/A |

The case studies provided additional context on the achievement of the ADRP’s intermediate outcome. Survey results showed there was lower satisfaction among producers involved in weather-related AgriRecovery initiatives, particularly forage shortfall initiatives, compared with those that were disease-related. Two of the five weather-related initiatives for which producer survey data were available did not meet the 75 per cent satisfaction target. Conversely, results from all four disease-related initiatives for which survey results were available indicated producer satisfaction targets were met. While these results are not conclusive, they were supported by key informant interviews with AAFC officials, some of whom indicated that AgriRecovery responses to disease-related disasters had a greater impact on the affected sector than responses to weather-related disasters.