Set up an interview

Media Relations

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

1-866-345-7972

aafc.mediarelations-relationsmedias.aac@agr.gc.ca

Earth’s biodiversity is one of agriculture’s best tools for adapting to climate change and guarding against future threats. From disease-resistant crops to natural predators, scientists are reaching into nature’s toolbox for answers. But where can they begin?

"Imagine a library with millions of books with no computer to look up the title or the author," says Dr. Heather Cole, Biodiversity Data Manager at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC).

Heather and her colleagues oversee the digitization of AAFC’s biological reference collections, which hold over 19 million physical specimens of plants, insects, fungi, bacteria and nematodes in Ottawa, Ontario. With specimens dating back centuries, each identified by a handwritten or typewritten label, many remained largely hidden and unknown.

To unlock this information, AAFC undertook a six-year, $30-million initiative known as "Biological Collections and Data Mobilization," or "BioMob" for short. The goal was to digitally catalogue the specimens and make them accessible by uploading photographs and other important information, including the DNA of select specimens! Having this information digitally available allows AAFC staff and other researchers to search for specific species or look for trends. By investing in new equipment and facilities and hiring a dedicated team during its six-year run, the initiative boosted the collections’ speed and capacity for digitization, paving the way for continued work even after the project’s official end in March 2022.

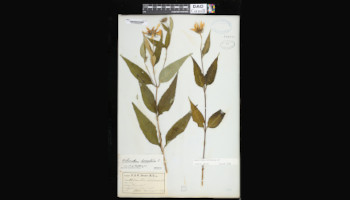

Among the collections, AAFC’s National Collection of Vascular Plants alone holds 1.5 million specimens and is the largest herbarium of its kind in the country. With the help of a new high-throughput imaging system, Heather’s team photographed up to 2,000 herbarium specimens per day, amounting to over 600,000 specimens during the course of the project. Now, she and a growing army of more than 1,000 online citizen science volunteers are manually entering the information from each specimen’s label – what it is, where it was found, who collected it and when – to ultimately link the information and images together in the herbarium database. A similar project with the entomology specimens was launched in October 2022. By making the data more accessible, the team’s efforts are opening doors to a range of new possibilities.

"The data represents so much information and value for all kinds of different reasons. Whether you're a researcher looking at what fungus affects an agricultural crop, or you just think butterflies are cool, there’s a little bit of something for everyone."

- Dr. Heather Cole, Biodiversity Data Manager, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Descriptive Transcript

[Upbeat electronic music starts.] [A close up view of Virginia pine needles and cones on a white background.]

[A scale bar positioned below a typewritten label with a description of a Pinus virginiana specimen collected in 1975.]

[A close up view of a typewritten label stating 'High-throughput Imaging System', with a scale bar positioned below it.]

[A woman places on a conveyor system a series of trays with herbarium specimens of dry-preserved leaves and flowers on white paper. Each specimen has a barcode, and label with descriptive text. The trays of specimens move through the imaging system process. The trays stop in a position surrounded by lights and an overhead camera. Plant specimens on trays roll along the conveyer belt. A camera displays a picture of one of the images of a pressed plant specimen. A woman removes the specimen from the tray and places the empty tray on the return ramp. She examines the image of the plant specimen on the computer monitor. An overhead view of multiple images of pressed plant specimens with flowers and leaves.]

[Music ends.]

[Government of Canada wordmark.]

[End.]

Identity confirmed

Digital images are especially useful "for inspection agencies monitoring invasive or pest species," says Dr. Owen Lonsdale, manager of the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes (CNC) at AAFC. Holding over 18 million specimens, this collection is among the five largest collections of its kind in the world. With help from cameras, many students and term technicians funded through the BioMob project, his team added almost 2.6 million new records to the database and generated 850,000 images for use worldwide.

"For anyone identifying material in the absence of a research collection, the possibility of misidentification is very high," Owen explains. "The differences can be incredibly slight, and making a mistake in identification can have huge ramifications." By correctly identifying a pest, regulators can stop the import or export of pests in agricultural products and farmers can prevent damage to their crops.

Tracking habitats and wild relatives

Another need for digitized biodiversity data is to track changes to a species' habitat over time. This is important for keeping tabs on invasive species or the impacts of climate change. "Or maybe you’re a teacher who wants to take your class somewhere cool, where you know you can find a lot of different species," Heather adds.

Besides helping educators find biodiversity hotspots, the digitized data can help researchers examine a particular species and see how it’s changed to adapt to different environments over time. A plant growing in the Northwest Territories might look different from the same species growing in Ontario, Heather offers, as an example.

The collection’s data can also be used to find wild relatives of food crops. Genetically similar to the agricultural crops grown today, these naturally occurring species haven’t gone through the same decades-long breeding process to make them suitable for cultivation. "If we have local species, they may have traits that help them do well in our environments," says Heather. Useful characteristics might include a hairiness trait that helps the crop seem less appealing to insect pests.

Natural pest solutions

Using a hundred years’ worth of pest-rearing records from the CNC, links can be made between different species with their natural predators – information that could be used by scientists to identify natural solutions to agricultural pests.

"Instead of putting them on a pin right away," Owen says of the entomology specimens, "[researchers] wait to see if anything emerges from them." Known as parasitoids, these wasps or flies lay eggs inside other bugs, eventually consuming the host from the inside out when they hatch. It’s nature’s way of controlling pests in the wild, and the same parasitoids can sometimes be used to manage pests in a farmer’s crop – a technique known as biocontrol. Currently being piloted online, this interactive map shows the distribution of a known pest species, the Eastern tent caterpillar, and several of its parasitoids.

"We [also] have a lot of people interested in what flies, bees and other organisms are pollinating native wild plants and crops growing here in Canada," Owen adds. With this data digitized, they can pull up a list of pests or pollinators by searching for almost any plant or crop in Canada, and vice versa.

Gathering DNA fingerprints

Plants and bugs can often be identified by eye, but for very closely related species, or for smaller organisms like bacteria, viruses and fungi, researchers often rely on DNA. Each species has a unique genetic fingerprint, and small parts of it can be “scanned” by researchers like a grocery store barcode.

"Say you went into your backyard, got a scoop of soil, and sequenced all the bacterial or fungal DNA," says Dr. Jeremy Dettman, the AAFC lead on molecular characterization for the BioMob project. By scanning DNA barcodes from the soil sample, scientists can match them against entries in the database and identify the bacteria or fungi present – but success depends on how much information is contained in the database. The BioMob project allowed Jeremy’s group to sequence 19,000 DNA barcodes and 7,500 complete or partial genomes from AAFC specimens, making new reference data available around the world. "Now instead of getting an unknown organism, they'll have a hit to a known organism with a name and biology," he says.

"We're laying the foundation to support future research on biodiversity and all the work that relies on these collections and molecular data."

- Dr. Jeremy Dettman, Research Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Crop breeders and researchers can also use the genetic database to help crops adapt to a rapidly changing climate. Working with seed collections from the Plant Gene Resources of Canada (PGRC) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Jeremy’s team extracted and recorded the DNA of select crops and wild relatives. This DNA database can help plant breeders more quickly find related plants with the characteristics they’re interested in, such as tolerance to drought or resistance to disease, vastly speeding up the lengthy breeding process.

Next Steps

About 50,000 new specimens are added to the biological collections every year. Altogether, the BioMob project digitized over 1.4 million new specimens and added nearly 3.5 million records to AAFC’s catalogue – data that can now be shared more easily by request. They’ve also begun uploading data to open-access resources, such as Canada Open Data Portal, Mycoportal, and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

"We have only just scratched the surface," says Owen, pointing to nearly 16 million specimens left to document. But by taking the first big steps towards digitization, the team is now set up to continue unlocking data from these invaluable specimens.

"[By] looking at the data, we're making a lot of discoveries that we never really knew was there before. It’s leading to new avenues of research that we wouldn’t have been able to see," he says.

Key discoveries/Benefits

- Running from 2016 to 2022, the BioMob project invested $30 million into DNA analysis, data capture and imaging of specimens from AAFC’s biological collections, which included invertebrates, vascular plants, fungi, plant and animal genes, viruses and bacteria

- The goal was to improve the accessibility and usability of the data from these collections to benefit the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector

- The work added or updated over 3.5 million specimen records, 1.4 million new specimen images and nearly 19,000 DNA barcodes

Photo gallery

Known to staff as 'Herbie,' this high-throughput digitization system captured images of up to 2,000 herbarium samples per day, making this data readily accessible.

Collected in 1978, this Dryas integrifolia is a member of the rose family and the floral emblem of the Northwest Territories.

Collections preserve records of biodiversity. Collected in 1849, this native sunflower species is a wild crop relative whose genetics can be considered for crop breeding.

A captured image of Geloharpya confluens tanganjicae from a specimen dating back to 1978.

Dr. Owen Lonsdale leads a tour of the entomology specimens, which are typically pinned or preserved, and more difficult to image.

This fossilized neuropteran (commonly known as lacewing) is one of the many specimens in the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes (CNC), one of the five largest collections of its kind in the world.

Related information

- AAFC's Genetic resources and biological collections

- Notes from Nature - Volunteer to Digitize Biological Collections in Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Biological Collections - Interactive Map

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility - Open access biodiversity data

- Video: Herbarium High-throughput Imaging System