March 14, 2016

Report:

Office of Audit and Evaluation

Acronyms

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- BRM

- Business Risk Management

- CATI

- Computer Assisted Telephone Interview

- CAWI

- Computer Assisted Web Interview

- FDMS

- Farm Debt Mediation Service

- FPPI

- Farm product price index

- FTE

- Full Time Equivalent

- GF

- Growing Forward

- GF2

- Growing Forward 2

- USDA

- United States Department of Agriculture

Executive summary

Background

The Farm Debt Mediation Service (FDMS) is a statutory A-base funded program governed by the Farm Debt Mediation Act. The mandate of the FDMS, as established by the Farm Debt Mediation Act, is to help bring producers and their creditors together with a mediator in a neutral forum to reach a mutually acceptable agreement on farm debt and financial obligations.

Key findings

With respect to relevance, the evaluation found that there continues to be a need for a neutral service that offers financial mediation for farmers who are experiencing difficulty meeting their debt obligations. There are a number of factors that affect producers' control over the financial viability of their farm operations, many of which are unpredictable, such as weather and disease. As a valuable part of a larger suite of programs offered by AAFC, FDMS offers producers the opportunity to work with their creditors to come to a mutually acceptable agreement on their debt obligations.

The FDMS is a unique service that complements other federal and provincial/territorial programs and aligns with federal priorities and AAFC's strategic outcomes. The FDMS plays an important federal role as it provides consistency in policies and quality of services across the provinces/territories.

In terms of the achievement of intended results, the FDMS is largely achieving its intended outputs and outcomes; however, creditors have somewhat mixed opinions with regard to the performance and impact of the program. Program data and survey results indicate that the FDMS is having the desired impact on producers, and therefore, the program is achieving its intended results. Agreements are being signed, producers' financial situations are improving and there is evidence that the FDMS is having a lasting impact on producers' personal and business goals.

The majority of creditors would recommend the program to producers and indicated that the FDMS serves as an effective source of communication between producers and creditors during difficult times. However, compared to producers and mediators/financial consultants, creditors were less satisfied with their participation in the FDMS. This could partially be explained by the fact that 30 per cent of creditors believe that they received less money from the FDMS process than if they had not participated.

In terms of program efficiency, although the decrease in demand for the program has resulted in an increase in costs per participant, the restructuring of the program in 2012 has helped to reduce overall costs. However, as the FDMS is legislated and thus obligated to respond to demand, an analysis of cost per participant must be viewed within the context that demand for the program could rise in the future and that the program needs to be prepared to meet this potential demand.

FDMS would be more effective if producers were more aware of the program, accessed it earlier and were provided with follow-up after an agreement was signed. Key informant interviews indicated that many producers are not applying to the program early enough to be able to explore options apart from selling assets or possibly selling their farms. The evaluation survey results indicate that producers are typically not familiar with the FDMS. Producers primarily learn about the program from their creditors only once they are in severe financial difficulty. Producers could potentially see more benefits from the FDMS if they became aware of and applied to the program earlier.

The evaluation found that the FDMS would be more effective if follow-up was provided to producers after the agreement was signed. This would allow the program to provide assistance to producers who are having difficulties implementing their agreements. It would also provide the opportunity for the program to collect important performance information to support ongoing improvements of the program, evaluations and legislative reviews.

1.0 Introduction

The evaluation was undertaken by AAFC's Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE) as part of AAFC's Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan (2014-15 to 2018-19). The evaluation fulfills the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation (2009). This report presents the findings of the evaluation of the Farm Debt Mediation Service (FDMS).

FDMS is a statutory A-base funded program governed by the Farm Debt Mediation Act. Its mandate, as established by the Act, is to provide free and confidential financial counseling and mediation services to farmers who are experiencing difficulties repaying their debts.

1.1 Evaluation scope

As FDMS has not been previously evaluated, the evaluation took a comprehensive approach, assessing equally the relevance and performance of the program. The evaluation covered the period from 2008-09 to 2014-15. In terms of performance, the evaluation focused on analysing the program's achievement of intended outcomes, with particular emphasis on assessing the efficiency of program design and delivery. The evaluation addressed the following core evaluation issues in accordance with the Treasury Board of Canada's Directive on the Evaluation Function (2009):

1.2 Evaluation issues and questions

- Relevance

- 1. Assessment of the extent to which the FDMS continues to address a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians.

- 2. Assessment of the linkages between the FDMS objectives and

- federal government priorities and

- departmental strategic outcomes.

- 3. Assessment of AAFC's role and responsibilities in delivering the FDMS.

- Performance

- 4. Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes with reference to performance targets and program reach, program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

- 5. Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

2.0 Program profile

2.1 Program context

Legislation to assist producers who are experiencing debt problems has been in place in Canada since the late 1930s. The Farmers' Creditors and Arrangement Act was the federal government's response to the unusually high levels of insolvency caused by the Great Depression and the drought in the western provinces during the 1930s. After being dormant for many decades, the Farmers' Creditors and Arrangement Act was replaced in 1986 by the Farm Debt Review Act. The Farm Debt Review Act served to assist with the resolution of debt problems of an unusually large number of farmers that were experiencing financial difficulty in the early to mid-eighties. In April 1997, the Farm Debt Review Act was repealed and replaced by the Farm Debt Mediation Act, which added mediation services to the program. The Farm Debt Mediation Act provides AAFC with the authority and statutory obligation to deliver the FDMS.

2.2 Overview of the program

The mandate of the FDMS is to bring producers and their creditors together with a mediator in a neutral forum to reach a mutually acceptable agreement on farm debt and financial obligations. The FDMS is a free and confidential service designed to provide financial and mediation services to producersFootnote 1 who farm commercially and meet one of the following criteria:

- are unable to pay or have ceased paying their current debt; or

- if sold, the value of their assets would not be sufficient to cover the cost of their debts.

The financial services provided by the program include: a detailed review of the producer's financial situation, preparation of financial statements and a recovery plan. The mediation services involve a meeting between the producer and creditor(s) facilitated by a mediator. A producer's participation in the FDMS does not affect his/her credit rating. A creditor's participation in the FDMS is voluntary.

In order to be eligible for the FDMS, a producer cannot have applied to the program in the past two years and must qualify under one of the following situations:

- Section 5(1)(a) - Farmers who have received notice that their creditors intend to realize on their security and they want to stop any further action against them. In this situation, the FDMS provides a stay of proceedings (which stops any action by creditor(s)), a financial review and mediation.

- Section 5(1)(b) - Farmers who can foresee financial difficulties although their creditors have not taken action against them to collect. In this situation, the FDMS does not provide a stay of proceedings but does provide a financial review and mediation.

Program administration was consolidated in 2012 from five regional offices to two (East and West). For 2014-2015, the program staff complement consists of 11.8 FTEs: 3.6 in the West, 7.7 in the East (0.9 Ontario, 3.8 Quebec and 3.0 Atlantic) and 0.5 at National Headquarters in Ottawa. The FDMS also provides a toll-free service to producers to answer questions about the program.

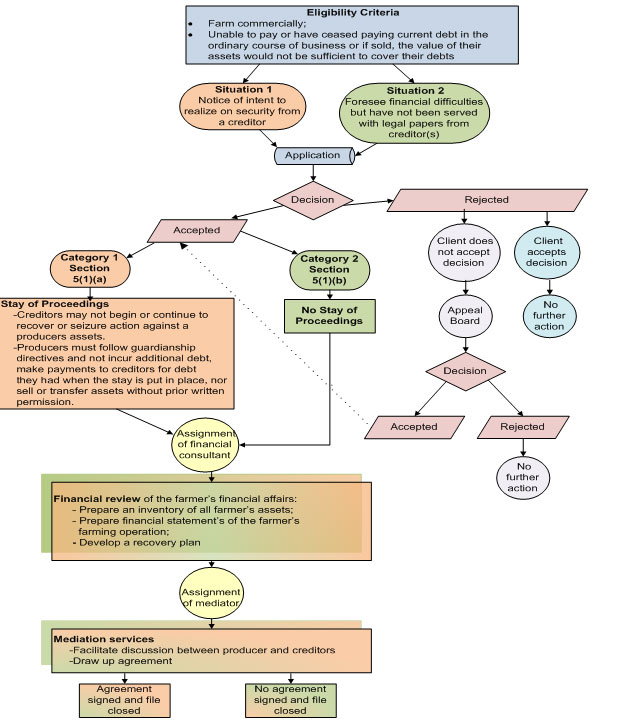

AAFC staff in the regional offices review the applications, make the requests for stays of proceeding, assign the financial consultant and mediators and assist in planning the logistics for mediation meetings. The financial review services under FDMS are provided by private sector financial consultants and mediators who have standing offers with one of the regional offices. The financial consultants and mediators have been qualified through a competitive contracting process which AAFC has approved. The amount of remuneration that consultants and mediators receive for each case is predetermined and fixed in the standing offer. An overview of the application, financial review and mediation processes are outlined in figure 1.

Description - Figure 1

Eligibility criteria

- Farm commercially;

- Unable to pay or have ceased paying current debt in the ordinary course of business or if sold, the value of their assets would not be sufficient to cover their debts

This leads to two possible situations:

- Situation 1

- Notice of intent to realize on security from a creditor

- Situation 2

- Foresee financial difficulties but have not been serviced with legal papers from creditor(s)

Both situations lead to an Application, which leads to a decision between being Accepted or Rejected.

Accepted

There are two categories.

- Category 1, section 5(1)(a)

Stay of Proceedings- Creditors may not begin or continue to recover or seizure action against a producer's assets

- Producers must follow guardianship directives and not incur additional debt, make payments to creditors for debt they had when the stay is put in place, nor sell or transfer assets without prior written permission

- Category 1, section 5(1)(b)

- Leads to no stay of proceedings.

Both categories lead to an assignment of financial consultant, which leads to a Financial review of the farmer's financial affairs:

- Prepare an inventory of all farmer's assets;

- Prepare financial statements of the farmer's farming operation;

- Develop a recovery plan

Assignment of mediator leads to

Mediation services

- Facilitate discussion between producer and creditors

- Draw up agreement

There is either an agreement signed and file closed or no agreement signed and file closed

Rejected decision Leads to either

- Client accepts decision, then no further action; or

- Client does not accept decision, Appeal Board, and either an accepted or rejected response

2.3 Program resources

FDMS is a statutory A-base program. Its annual non-pay operating allocation fluctuates as it is a demand-driven program. The non-pay operating funding pays for the financial consultants and mediators. As illustrated in Table 2.1, over a six year period (2008-2009 to 2013-2014), FDMS's planned budget was $23.9 million in Vote 1 funding ($8.4M in Salary and $15.6M in non-pay operating).

| Year | Salary ($) | Non-Pay Operating ($) | Total ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-2009 | 1,167,086 | 1,739,000 | 2,906,086 |

| 2009-2010 | 1,439,016 | 2,563,587 | 4,002,603 |

| 2010-2011 | 1,601,000 | 3,376,450 | 4,977,450 |

| 2011-2012 | 1,495,000 | 3,057,000 | 4,552,000 |

| 2012-2013 | 1,395,085 | 1,817,635 | 3,212,720 |

| 2013-2014 | 1,266,468 | 3,000,000 | 4,266,468 |

| Total | 8,363,655 | 15,553,672 | 23,917,327 |

| Source: AAFC Program Data | |||

3.0 Evaluation methodology

3.1 Data collection methods

The evaluation of FDMS relied on multiple lines of evidence including surveys of program stakeholders, key informant interviews, case studies and analysis of program administrative data. By using multiple lines of evidence and triangulating findings, the research methodology supported a comprehensive evaluation of the program.

- Document review

A total of 55 documents were reviewed as part of the evaluation. The document review addressed the evaluation issues related to relevance. It examined, for example, publications on the financial situation of farmers, the Farm Debt Mediation Act, speeches from the throne, federal budgets, AAFC reports on plans and priorities, reports to parliament on the FDMS and departmental performance reports.

- Review of program performance data

The review of program data included an analysis of all 2,685 FDMS applications received by the program during the period from August 1, 2008 to September 30, 2014, including 2,482 accepted applications.Footnote 2 It examined file information collected by the program during the mediation and after it had concluded. The analysis included information on how the FDMS was being used (type of application), who was using it (province, primary commodity, size of operation, participation in other programs, and creditors), when producers were using it (month and year), and the outcomes of a producer's participation (agreement being formed between creditors and debtors, terms of agreement).

The evaluation incorporated other administrative data including program expenditure data (salaries and other operating expenditures) and information on business analysts/mediators (for example, costs). Data were accessed from Statistics Canada and the Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada to demonstrate the overall financial health of Canadian agriculture, as well as to track changes in farm commodity prices.

- Key informant interviews

An initial 25 key informant interviews were conducted by the Office of Audit and Evaluation between August and October 2013 to gain an understanding of the program, to identify the main questions/issues that would be addressed by the evaluation and to develop a full methodological plan for the evaluation. Respondents were included from the following categories of program stakeholders:

- FDMS Staff (n=6);

- Mediators (n=4);

- Financial Consultants (n=4);

- Creditors (n=7); and,

- Producers (n=4).

After a preliminary analysis of the data collected through these early interviews, themes and areas of interest were identified for further investigation. An additional 14 interviews, using updated interview guides, were conducted from January to March of 2015 with the following stakeholders:

- additional AAFC and FDMS staff (n=6);

- banking experts and farm credit organizations (n=4); and,

- representatives of farming industry organizations (n=4).

- Surveys

Three separate surveys were conducted to collect feedback from producers, creditors and financial consultants/mediators. The three questionnaires were programmed into CallWeb, a Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI)/Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) system allowing for the surveys to be completed over the phone or online. The programmed questionnaires were then tested for functionality and ease of administration prior to contacting respondents.

Producers, creditors and financial consultants/mediators were randomly selected from the FDMS database to participate in the surveys. In order to maximize response rates, and to help promote an "informed" discussion about the program, all participants were sent pre-survey communication. This included letters mailed to the producer sample and e-mails to the sample of creditors and financial consultants/mediators. Following field testing, survey administration began on March 10th, 2015 and was completed on March 30th, 2015.

Completion targets were established for each cohort in order to ensure statistical reliability and considering resources available for the evaluation. In addition, completion quotas were established to help ensure that the survey had adequate representation from all regions of the country. As highlighted in Table 3.1, the surveys generally met completion targets for all groups with the exception of the financial consultants/mediator sample.Footnote 3

Table 3.1: Key survey metrics by cohort Group Initial Sample Valid Sample Target Completions Actual Completions % of Target Response Rate (%) Estimated Sample Error1 (%) Producers 1,580 1,208 225 232 103 19.2 ±6.1 Creditors 295 254 50 52 104 20.5 ±12.9 Mediators/Finc.

Consultants62 58 25 23 92 39.7 ±16.5 Total 1,937 1,520 300 307 102 20.2 n/a 1 At the 95% confidence interval To ensure that the survey results were representative of the entire producer population, survey data for the producer survey was weighted to reflect regional participation in the program. Given the small sample for the creditor and mediator/financial consultant survey, data for these groups were not weighted.

Analysis of the survey data suggests that there was no specific non-response to the survey on the basis of region, year of program application, or whether mediation was completed. Therefore, the survey results were deemed to be a reliable portrayal of producer, creditor and mediator/financial consultant opinions with respect to the FDMS.

- Case studies

While not intending to represent the views of all FDMS applicants, the case studies aimed to provide insights as to how the individuals perceived the value of his/her participation in the program. Four producers from a variety of regions and commodity groups across Canada were selected as case studies:

- Case Study 1: A mid-sized grain farmer in Saskatchewan who applied to the program in 2013 seeking a stay of proceedings;

- Case Study 2: A mid-sized horticultural producer in Prince Edward Island who applied to the program in 2011 seeking a stay of proceedings;

- Case Study 3: A small-sized beef farmer in Ontario who applied for the program in 2009 and in 2013, both instances involving a stay of proceedings; and,

- Case Study 4: A large-sized hog producer in Quebec who applied to the program in 2011, without a stay of proceedings.

3.2 Methodological considerations

The evaluation had three considerations in assessing the FDMS.

- Limited ability to ascertain the net or incremental impact of the program. While producers and creditors were asked to hypothesize what would have happened in the absence of the program, it was not possible to definitively identify the outcomes of affected farmers had the FDMS not existed. The structure of the evaluation did not allow for a comparison to the counter-factional (i.e. outcomes in the absence of the program). This limitation was mitigated by using multiple lines of evidence and triangulating findings as discussed above.

- Difficulties in using administrative data. While the FDMS applicant database may be well-structured to support program activities, it was not suited to support performance measurement or program evaluation. For example, producer records were not uniquely identified, leading to challenges in the measurement of the number of unique or repeat users of the FDMS. There was also limited linkage to farm administrative data (amount of debt, debt history) and outcome data were not collected or maintained in the administrative data. These challenges were mitigated through the development of the analysis dataset.

- Inability to conduct a full cost-benefit analysis of the program. The scope of the evaluation did not allow for a full cost-benefit analysis of the FDMS. While it was possible to detail the average cost per file for the FDMS, it was not possible to measure broader societal benefits associated with the program, such as reduced court costs for producers and creditors, increased GDP as a result of more farms maintaining operations and increased business confidence.

4.0 Evaluation findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued need for the program

The evaluation found that there continues to be a need for a neutral service that offers financial mediation for farmers who are experiencing difficulty paying their debts. A number of factors affect producers' control over the financial viability of their business. The agriculture sector is cyclical and thus producers' need for debt mediation services fluctuates based on the economic conditions facing the agriculture industry. As a component of AAFC's overall industry capacity and business risk management programs, financial and mediation services offer producers who find themselves in financial difficulties the opportunity to work with their creditors to come to a mutually acceptable agreement on their debt obligations.

Broader societal and economic need for FDMS

The agriculture sector faces a wide range of risks, many of which are beyond producers' control. Production risks include unfavourable weather conditions (drought, unseasonably cold or hot weather, and heavy moisture) and crop pests and disease. All of these can prevent planting, negatively impact farm yields and the quality of crops, and delay harvest.

The producer from case study one reported that they needed the FDMS because of falling commodity prices, recent crop losses due to weather or disease, as well as a debt burden from other loans. The farmer viewed themselves as being financially savvy, reporting that they were well aware of their financial situation prior to accessing the program.

There are also a number of market risks that impact producers' business. Producers face fluctuating fuel, fertilizer and feed costs. Prices for crops are determined in large part by global markets, which are outside producers' control. The fact that agriculture is an export sector also places farmers at risk due to the variability of transportation costs and exchange rates, as well as tariff and non-tariff barriers. Other risks for producers include the business risks associated with the management of revenue and cash flow to pay bills, labour employment and interest rates. Farmers also face risks associated with changing government policies and programs, tax rates and the impacts of international trade agreements.

The 2013 Strategic Issues survey conducted for AAFC found that natural disasters and weather fluctuations are the main business risks faced by producers (52%), followed by market price fluctuation and volatility (29%), and disease or pests (24%).Footnote 4 These factors affect producers' control over the financial viability of their business and thus, their ability to pay their debts from year-to-year.

Cyclical Demand for Debt Mediation Services

Since the agriculture sector is cyclical, producers' need for debt mediation services fluctuates based on the economic conditions facing the agriculture industry. Similar to many resource-based sectors, Canada's agricultural industry can be characterized as "cyclical", subject to worldwide commodity price swings that affect supply, and to a lesser extent, demand. As discussed above, the sector also faces a variety of trade, regulatory and environmental issues that can affect profitability.

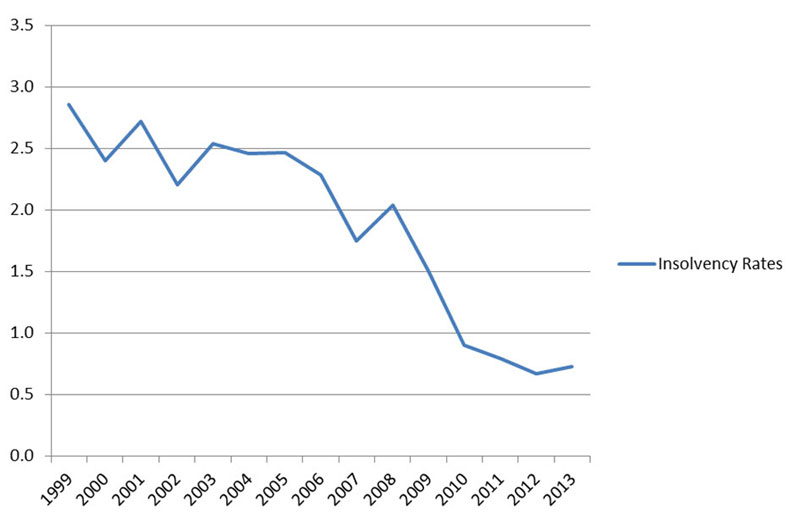

According to the 2011 Report to Parliament on the Farm Debt Mediation Act, the number of applications received under the FDMS peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a result of high rates of insolvency largely due to high interest rates, low commodity prices and decreasing asset values in some regions. As interest rates rapidly declined and commodity prices and asset values rose, the sector began to experience more stability. As shown in Figure 2 below, this trend has continued as business insolvency rates for the Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting sectorFootnote 5 have been decreasing since 2000. In terms of the time period covered by this evaluation, there was an increase in the insolvency rate in 2008-2009, likely due to the global economic recession, but then a significant decline from 2009-2012 where the rate decreased by over 50 per cent.

Description - Figure 2

| Year | Insolvency Rates |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 2.9 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2000 | 2.4 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2001 | 2.7 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2002 | 2.2 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2003 | 2.5 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2004 | 2.5 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2005 | 2.5 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2006 | 2.3 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2007 | 1.8 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2008 | 2.0 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2009 | 1.5 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2010 | 0.9 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2011 | 0.8 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2012 | 0.7 per every 1000 businesses |

| 2013 | 0.7 per every 1000 businesses |

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada, 2015

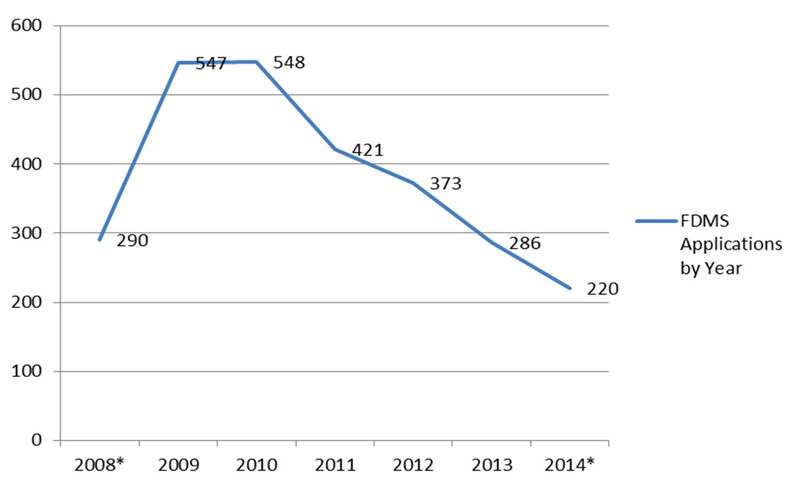

As highlighted in Figure 3, the demand for the FDMS has followed a similar pattern to insolvency rates. During the period from August 1, 2008 to September 30, 2014, the FDMS processed 2,685 applications. More than 40% of the applications occurred in two years (2009 and 2010), which again correlates with the onset of the global recession in 2008. Since 2010, applications to the FDMS have declined by 60%; from 548 applications in 2010 to 220 applications in 2014. This suggests that the demand for the FDMS services is tightly linked to the financial health of the agriculture sector, as measured by the rate of bankruptcies.

Description - Figure 3

| Year | FDMS Applications by Year |

|---|---|

| 2008* | 290 |

| 2009 | 547 |

| 2010 | 548 |

| 2011 | 421 |

| 2012 | 373 |

| 2013 | 286 |

| 2014* | 220 |

Source: AAFC FDMS Administrative Data

*Note: 2008 and 2014 are only partial years; 5 and 9 months, respectively.

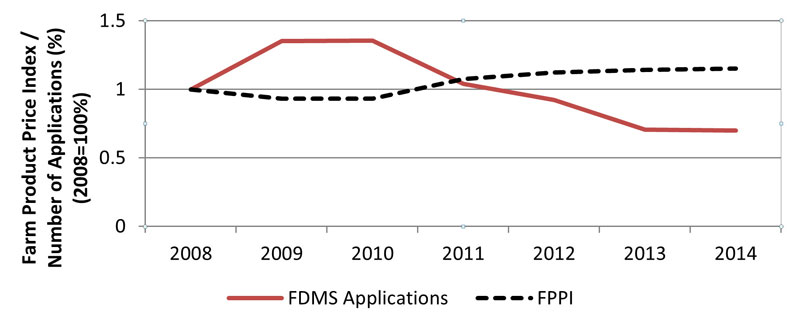

As highlighted in Figure 4, demand for the FDMS has recently been inversely correlated with farm commodity prices. During periods in which agricultural prices were in decline (2009-2010), demand for the FDMS was high. Conversely, with the significant increase in farm commodity prices from 2010 to 2013 (up by almost 25%), demand for the FDMS has steadily declined. That said, other factors can also impact demand for the FDMS, such as increases or decreases in off-farm income, changes in the credit market or interest rates.

Description - Figure 4

| Year | Farm debt mediation service applications |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 1 |

| 2009 | 1.35 |

| 2010 | 1.35 |

| 2011 | 1.04 |

| 2012 | 0.92 |

| 2013 | 0.71 |

| July-05 (2014) | 0.7 |

| Year | Farm product price index |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 1 |

| 2009 | 0.93 |

| 2010 | 0.93 |

| 2011 | 1.08 |

| 2012 | 1.12 |

| 2013 | 1.14 |

| July-05 (2014) | 1.15 |

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 002-0069 - Farm product price index (FPPI), annual (index, 2007=100), CANSIM (database).

Source: AAFC Program Data, FDMS Financial Data

*Due to 2008 and 2014 being only partial years the number of applications within these years was estimated based upon the historic distribution of applications per quarter.

To summarize the above analysis, the demand for FDMS services is generally correlated with both bankruptcies and commodity prices. The greater the bankruptcy rate, the greater the demand for FDMS. Similarly, higher commodity prices generally result in a lower demand for FDMS, whereas lower prices increase demand. Other economic factors, such as energy prices, labour trends, interest rates, etc., also play a significant role. This suggests that the demand for FDMS is tightly linked to the overall economic conditions in Canada.

Many key informants also referred to the changing structure of the farming industry as having an influence on the demand for the FDMS. Canada has been experiencing a shift to fewer, larger farms. It is possible that the trend towards larger farms may increase the demand for the FDMS.

According to program data, larger farms (over $100,001 in gross farm receipts) access the program disproportionately higher and are the largest size category of applications to the FDMS (58.3%) (see Table 4.1). With the recent trend toward farm consolidation, there is a greater need for technology to make farms more sophisticated and profitable (such as machinery to enhance productivity). Canadian farms also face greater competition with producers across the country and internationally. This pressure, coupled with easier access to and greater need for credit, leads to producers carrying larger debts and increases their financial risks. This could then lead to greater demand for the FDMS.

(Aug. 1, 2008 to Sept. 30, 2014)

| Total Gross Farm Receipts | Number of Applications to FDMS Count |

Number of Applications to FDMS Per cent (%) |

Number of Farms (2011) Count |

Number of Farms (2011) Per cent (%) |

Applications as a % of Total Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than $25,000 | 342 | 17.8 | 76,807 | 37.3 | 0.45 |

| $25,000 to $100,000 | 457 | 23.9 | 51,219 | 24.9 | 0.89 |

| $100,001 to $250,000 | 453 | 23.6 | 31,670 | 15.4 | 1.43 |

| Over $250,000 | 664 | 34.7 | 46,034 | 22.4 | 1.44 |

| Valid Total | 1,916 | 100 | 205,730 | 100 | N/A |

| No Data | 769 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Grand Total | 2,685 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Source: AAFC FDMS Administrative Data Source: Statistics Canada. Table 004-0006 - Census of Agriculture, farms classified by total gross farm receipts at 2010 constant dollars, Canada and provinces, every 5 years (number) |

|||||

The evidence provided above suggests that the demand for the FDMS is linked to the overall economic conditions facing producers, which tends to fluctuate over time. The changing farm structure in Canada also plays a role in terms of the amount of debt and financial risk that producers are willing to assume, and therefore producers' needs in terms of debt mediation services.

Financial analysis and mediation services help producers restructure debt

The importance of AAFC's involvement in farm debt and mediation services was highlighted by a number of AAFC staff who saw the FDMS as an important part of a larger suite of business capacity building and risk management programs the department offers to producers. The FDMS complements AAFC's Fostering Business Development program, which supports the development of business management tools and information designed to increase competitiveness, innovation and risk management. The FDMS aims to improve producers' business capacity by helping producers who are in financial difficulties better understand their financial situation and by supporting them to develop a business plan that can be agreed upon with their creditors. In terms of business risk, AAFC has a number of programs that focus on helping producers in disaster situations. The FDMS supports this work by providing producers with a last line of defence when experiencing financial difficulties.

Mediation is defined as "the process by which the participants, together with the assistance of a neutral person or persons, systematically isolate disputed issues in order to develop options, consider alternatives and reach a consensual agreement that will accommodate their needs."Footnote 6 Mediation is a co-operative problem-solving process, designed to help the parties to a dispute find constructive solutions to problems.Footnote 7

The literature suggests that mediation services help producers better understand their financial situation and provide an opportunity to come to a mutually acceptable agreement with their creditors. This increases the likelihood that they will maintain their farm operations throughout the proceedingsFootnote 8 and is also less costly than using more traditional means of debt collection.Footnote 9 Mediation also provides farmers who are having difficulties meeting their debt obligations with guidance on their finances and how to manage them, which is a crucial step toward the producer developing a business plan that will allow him/her to maintain a viable business while meeting financial obligations.Footnote 10 It has also been found that parties engaged in mediation are more likely to follow through on the resulting agreements than those developed through court proceedings, as they participated in drafting them.Footnote 11

From a commercial perspective, mediation is an extension of the usual commercial process of negotiating an agreement and is likely to result in a satisfactory solution in which all parties benefit. Mediation serves a purpose beyond immediate assistance to those involved; it also results in longer-term changes in behaviour and processes to prevent further difficulties.Footnote 12

Some of the specific benefits of mediation noted in the literature include:

- puts control of the resolution of the dispute into the hands of those best equipped to find the most appropriate solution;

- provides an opportunity for parties to have their say in a confidential, non-threatening atmosphere;

- helps disputing parties understand how the others see and feel about the problem;

- enables business relationships to be maintained and even enhanced by encouraging cooperative problem solving;

- enables identification and exploration of all issues, including those which may not be revealed in arbitration or litigation due to the application of the rules of evidence;

- provides the opportunity for an unlimited range of creative and final solutions unlike the limited remedies which can be awarded by an arbitrator or a judge;

- is confidential thereby avoiding adverse publicity or media attention and the need for any confidential or commercially sensitive information to be publicly disclosed; and,

- is usually significantly cheaper and quicker than arbitration or litigation and can be arranged to suit the convenience of the parties.Footnote 13

The evaluation found that there continues to be a need for mediation services for producers who are experiencing financial difficulties. The thin operating margins of the Canadian agricultural industry combined with the unique risks the sector faces, underscores the need to have a debt management program available to the sector. The agriculture industry is cyclical and thus the demand for FDMS fluctuates based on market conditions. Mediation services complement the larger suite of AAFC business capacity building and risk management programs, and offer producers the opportunity to work with their creditors to develop a mutually acceptable agreement on farm debt obligations.

4.1.2 Alignment with federal priorities and departmental strategic outcomes

The FDMS is aligned with the priorities of the federal government and AAFC's strategic outcomes. Its objectives are consistent with Speeches from the Throne in 2006 and 2010, which specifically mention a federal government commitment to support producers to achieve long-term competitiveness and sustainability.

In addition, the FDMS aligns with AAFC's strategic outcome of a financially sustainable and competitive agri-business sector. Under AAFC's Performance Measurement Framework for 2011-2012, the FDMS falls under Agri-Business Development that builds awareness of the benefits and encourages the use of sound business management practices. Agri-Business Development aligns with AAFC's strategic outcome of "an innovative agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products sector". Key informants noted that FDMS plays a less direct but still important role in improving Canada's agriculture and agri-food sector and economic prosperity in general. Specifically, the FDMS plays a role in the development of industry capacity by promoting sound business management practices, and enabling businesses to be profitable and invest where neededFootnote 14.

4.1.3 Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

Governed by federal law under the Farm Debt Mediation Act, the FDMS plays an important federal role by providing consistency in policies and quality of services across Canada. Under the Farm Debt Mediation Act, AAFC's Minister is legislated to offer financial planning and mediation services to insolvent producers. AAFC's responsibilities are outlined in the Farm Debt Mediation Act and the accompanying regulation.

Key informants agree that it is appropriate for the federal government to provide the services offered through the FDMS. It was suggested that the FDMS should remain a federal program to maintain consistency in policies and quality of service. National banks also reported that they prefer to work with one organization for all cases in need of an FDMS type of intervention.

Further, if FDMS did not exist, some provinces would not be able to justify offering mediation services as demand for such services is quite low in some provinces. For example, over the six year period from 2008 to 2014, the FDMS only received 2.1 applications per year from Newfoundland and Labrador, and 7.7 from Prince Edward Island (on average over a six year period). It would likely not be possible to support a provincially run program with such little demand.

Demand also fluctuates by region and commodity, and thus a national program allows for more stability as regional fluctuations in demand tend to offset each other. For example, program demand has recently increased in Quebec and decreased in Western and Atlantic Canada. Producers in Quebec make up nearly half of all applications, yet make up less than one-sixth of all farms in Canada. Key informants mentioned a few key reasons for this change in demand:

- the Quebec farm industry has been heavily subsidized by the provincial government in the past, but this support has now been reduced significantly;

- until recently many Quebec-based farms were in the hog industry, which has faced a crisis in recent years;

- applications from other parts of Canada have declined as agriculture in Western Canada is dominated by grains and oilseed production, which has experienced a surge in profitability; and,

- farming in Atlantic Canada has generally decreased.

A national program allows for greater consistency in the number of applications to FDMS by offsetting changes in regional demand.

4.1.4 FDMS duplication and complementarity with other programs

The interview and document reviews suggest that the FDMS provides a unique service to producers, which is not duplicated by other federal and provincial departments or the private sector. In terms of programs similar to the FDMS, programs offered by the Saskatchewan and Manitoba governments offer debt mediation for producers, but do not provide financial analysis services. Most key informants stated in their interviews that there is no overlap or duplication among the FDMS and these provincial programs, but rather that they complement each other by offering services that meet a variety of producer needs. The Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act delivered by Industry Canada does provide some support to producers in financial difficulties, but does not offer mediated settlements.

The Government of Saskatchewan's Farm Land Security Board is a quasi-judicial tribunal funded, but not governed by the Ministry of Agriculture, which oversees farm foreclosures, Home Quarter Protection mechanisms and Farm Ownership regulations under The Saskatchewan Farm Security Act. When the Board receives a Notice of Intention to Foreclose, it reviews the farmer's financial situation and provides a report to its dispute resolution services, who will then attempt to mediate between the farmer and creditor. Farmer participation in the mediation is voluntary.Footnote 15 The Board, unlike the FDMS, is concerned with all matters pertaining to foreclosure, including the sale of land, but does not provide financial analysis service for producers similar to what is provided by the FDMS.

The Government of Manitoba has a Farm Industry Board. Its responsibilities include, among others, the mediation of disputes between farmers and creditors. This Board is tasked with preventing farmers from losing their operations when possible and protecting them (as well as creditors and vendors/dealers) during times of economic hardship. It differs from the FDMS primarily in that it is not only concerned with mediation, but also with farm machinery, farm land ownership, and the protection of farm practices. Similar to Saskatchewan, the program in Manitoba does not offer financial analysis services for producers.

Another option for producers across Canada is the procedures associated with the federal Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, which are delivered by Industry Canada. The Superintendent of Bankruptcy, the Bankruptcy Tribunal, the Official Receiver in Bankruptcy, and the bankruptcy trustee fall under the authority of Industry Canada. According to Industry Canada, a producer would have the following responsibilities under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act:

- attend two financial counselling sessions; and,

- assist the trustee in administering the bankruptcy or proposal.

Were a producer to file for bankruptcy, a trustee would become the administrator of the property and assets. The farmer would then have to:

- disclose all of their assets (property) and debts to the trustee;

- advise the trustee of any property disposed of in the past few years; and,

- surrender all credit cards to the trustee.

The trustee would then be authorized to wind up the property by selling all the assets and depositing the funds in trust for the creditors in bankruptcy.

Amongst interview respondents, opinions are mixed on whether producers' needs could be met by the work performed by Industry Canada under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act rather than services provided by FDMS. Many respondents raised concerns that there would be additional fees associated with using the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act. The Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act would also leave a record on a producer's credit rating, whereas this is not necessarily the case with the FDMS. The FDMS program itself cannot affect a producer's credit rating, however, it is up to the individual lenders whether or not a specific producer's credit rating will be affected. Interviewees noted that staff involved in the administration of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act would not have an in-depth understanding of the agricultural sector. Most importantly, there is no overlap between the services provided by the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act and FDMS: only the FDMS focuses on mediated settlements and although the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act does provide some financial services, they are not as extensive as the financial analysis and planning services provided through the FDMS.

Nearly three quarters of creditors (71.1%) reported that the financial institutions that they represent did not have a program that was similar to the FDMS (formal or informal) that assists in mediation with borrowers in the event of a default. Slightly more than one quarter of creditors who responded to the survey were aware of other programs or options. The following programs were mentioned in interviews with creditors:

- credit counselors;

- lawyers and trustees;

- bankruptcy aids under the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act; and,

- Saskatchewan Farmland Security Board.

Some key informants stated that for-profit services (such as creditors) might be able to offer alternatives to the FDMS, but that they would charge for similar services. Neutrality may be compromised if a business gets involved in negotiations between farmers and creditors. For example, one FDMS staff pointed out that bankruptcy trustees are often closely affiliated with banks, which are often creditors in the mediation process.

Mediation services offered to producers in other countries

Examples of programming similar to the FDMS offered in other countries provide further evidence for a federal role in providing FDMS type services. Key examples are services offered in the United States and Australia. The Farm Service Agency administers the United States Department of Agriculture Mediation Program. The Agricultural Credit Act of 1987 authorizes the Secretary of Agriculture to help States develop State Mediation Programs and participate in national Certified Mediation Programs.

State Mediation programs are developed to assist agricultural producers and their creditors to resolve disputes. The United States Department of Agriculture Mediation Program gives farmers and ranchers a confidential way to resolve disputes involving farm loans, conservation programs, wetland determinations, rural water loan programs, grazing on national forest system lands, pesticides, and other issues determined by the Secretary of Agriculture. Mediation services can include counseling and financial analysis to prepare parties for the mediation session.

In New South Wales, Australia, under its Farm Debt Mediation Act 1994, mediation is required before a creditor can take possession of property or other enforcement action under a farm mortgage. Farmers are advised to involve a professional advisor in the process; one option for such an advisor is a representative from the state's Financial Rural Counselling Service, a free and confidential service which provides information and assistance on financial position, budgets and submitting applications.

In conclusion, the evaluation found that the FDMS plays an important federal role as it provides consistency in policies and quality of services across Canada. The FDMS provides a unique service to producers that complements other federal and provincial programs and services provided by the private sector.

4.2 Performance – effectiveness

The FDMS is largely achieving its intended outputs and outcomes; however, creditors have somewhat mixed opinions with regard to the performance and impact of the program.

4.2.1 Outputs

The output indicators and targets outlined in the program's Performance Measurement Strategy do not support an assessment of the intended outputs, but rather are service standards.Footnote 16 The evaluation found that the FDMS has successfully achieved the program's intended outputs including:

- issuance of stay of proceedings;

- credible financial statements;

- credible recovery plans; and,

- neutral mediation meetings

There were a total of 2,685 applications received by the FDMS from 2008-2014, including 2,482 that were accepted. Of the accepted applications, 1,438 involved a stay of proceedings (Type 5(1)(a)), accounting for 57.9% of all FDMS files (see Table 4.2).

(1 Aug 2008 to 30 Sept. 2014)

| Application Type | Count | Per cent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5(1)(a) | 1,438 | 57.9 |

| 5(1)(b) | 1,044 | 42.1 |

| Total | 2,482 | 100 |

| Source: AAFC FDMS Administrative Data | ||

Producers reported through the evaluation survey that the FDMS provided credible financial statements and recovery plans and that they were satisfied with their mediation agreements. Most producers reported that the financial expert hired by the FDMS created an accurate profile of their operation (76%) and that the recovery plan that was developed over the course of the mediation process was appropriate (61%). Producers also indicated that the mediators worked hard to get them a fair settlement (65%) and were satisfied with the mediation agreement that was reached at the end of the mediation process (72%).

According to the survey, producers found the program easy to access (79%) and responsive (87%). Finally, producers who have used the program (87%) would recommend it to others who are in a similar position(s). Similarly, most creditors (83%) and mediators/financial consultant (100%) would also recommend the program to producers who are experiencing financial difficulties.

Creditor views on the FDMS are somewhat mixed despite their willingness to recommend the program to producers. Just over half of creditors (55%) were satisfied with the mediation agreement, while more than one fifth (22%) reported that they were dissatisfied. Half of creditors believed that the FDMS did meet their needs (51%); however, nearly one-third (31%) believed that the program did not (the remainder did not feel strongly either way). Creditors' mixed opinions on the FDMS could partially be explained by the fact that 30 per cent of creditors reported that they received less money as a result of the FDMS process than if they had not participated in FDMS, while 70 per cent said that they received the same amount or more.Footnote 17

Despite creditors' mixed opinions on the program, the evaluation found that the FDMS serves as an effective source of communication between producers and creditors during difficult times. Interviews with creditors indicated that the mediation meetings gave all parties a chance to convene and not only share perspectives, but also suggest ideas on how to address a producer's credit difficulties. While most creditors indicated that they did not gain substantial new information as a result of the FDMS process, almost all agreed that they benefited from their involvement in the FDMS. Creditors appreciated the more open communication with producers and mediators, and stated that they gained valuable knowledge on farm operations as a result. For example, one creditor explained, "I now understand how farms work. I work with other creditors [involved in the mediation] and learn what works and what doesn't."

In summary, the FDMS is achieving its outputs as outlined in its Performance Measurement Strategy. The program issues Stays of Proceeding as necessary and producers feel that the financial analysis services, recovery plans and mediation meetings provided by the program are satisfactory. Although creditors have a more negative perception of the program, they do believe that it provides an effective source of communication with producers.

4.2.2 Immediate outcomes

The FDMS is meeting its immediate outcomes of temporarily protecting farmers' assets and increasing producers' awareness of their financial situation (see Table 4.3). However, the program has not had a significant impact in terms of improving creditors' knowledge of their clients' financial situation.

| Immediate Outcome | Indicator | Target (%) | Actual (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers' assets are temporarily protected | Per cent of total completed applications under Section 5-(1)-(a) | 53 | 57.9 |

| Farmers have a greater understanding of their financial situation | Per cent of farmers who have a better understanding of their financial situation as a result of participation in FDMS | 85 | 85% reported having a strong understanding prior to FDMS, and 96% had a strong understanding after FDMS* |

| Creditors have a greater understanding of the clients' financial situation | Per cent of creditors who feel that the information developed by the financial consultant provided them with a better understanding of the farmers financial situation | 85 | Not available |

| AAFC: FDMS Program Performance Measurement and Risk Management Strategy (PPMRMS) *The questions included in the survey conducted for this evaluation are different from those used to develop the program targets and therefore comparisons with this target should be used with caution. |

|||

As mentioned in the previous section, 59.2 per cent of total completed applications were under Section 5(1) (a). In the evaluation survey, producers were asked about their awareness of their financial situation before and after accessing the FDMS. The large majority of farmers (85%) believed that they were aware of their financial situation prior to accessing the FDMS (Figure 5).Footnote 18 However, a greater number of farmers (96%) believed that they were aware of their financial situation after their participation in the FDMS. Although this increase is significantFootnote 19, it should be emphasized that producers' knowledge of their financial situation was quite high prior to their participation in the FDMS.

Description - Figure 5

| Awareness of Financial Situation | Per cent (%) |

|---|---|

| Unaware of Financial Situation | 1.6 |

| Somewhat Unaware | 4.8 |

| Neither Aware Nor Unaware | 8.6 |

| Somewhat Aware | 18.6 |

| Well Aware of Financial Situation | 66.4 |

| Awareness of Financial Situation | Per cent (%) |

|---|---|

| Unaware of Financial Situation | 1.2 |

| Somewhat Aware | 0.4 |

| Neither Aware Nor Unaware | 2.2 |

| Somewhat Aware | 15.6 |

| Well Aware of Financial Situation | 80.6 |

Source: AAFC Producer Survey 2015 conducted as part of the FDMS evaluation

Small producers benefit the most in terms of the FDMS increasing the awareness of their financial situation. Producers operating smaller operations tended to enter into the FDMS process with a lower level of awareness than those operating larger farms. Following their participation in the FDMS, the financial awareness of smaller-scale farmers was found to be the same as with the larger operations. This suggests that smaller-scale producers received a greater benefit than larger operations in terms of the program's impact on increasing financial awareness.

In terms of the indicator on creditors' understanding of their clients' financial situation, the questions included in the survey conducted for this evaluation are different from those used to develop the program targets and, therefore, comparisons with the target are not possible. However, according to the survey conducted for this evaluation, nearly the same number of creditors reported having improved their understanding of their client's financial situation (30%) as those who said it did not (28%). The program is, therefore, not having as significant of an impact on creditors as it is on producers in terms of increasing their knowledge of producers' financial situation.

4.2.3 Intermediate outcomes

The evidence suggests that the program is achieving its intended intermediate outcomes; however, data are not available for all indicators. The program is meeting its targets in terms of increasing the number of agreements between insolvent farmers and their creditors and farmers implementing activities to reduce debt and/or increase revenue (see Table 4.4). In terms of creditors suspending collection actions, there are no data currently available to assess this outcome. For the outcome of farmers advancing their personal and business goals, the program is meeting its target for the per cent of producers with an improved financial situation, but is below its target for the per cent of producers with reduced risk and credit problems.

In terms of the outcome of creditors achieving greater returns, the program has not met its target for the per cent of creditors with increased recovery of debt and data are not available for the per cent of creditors with lower costs of debt recovery. However, the indicator on creditors achieving greater returns may not be appropriate, as the goal of the program is not to achieve greater returns for creditors. It may be more appropriate to establish indicator(s) that measure the overall value creditors place on their participation in FDMS.

| Intermediate Outcome | Indicator | Target (%) | Actual (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased agreement between insolvent farmers and their creditors on financial recovery measures | Per cent of completed applications that resulted in signed arrangements between farmers and creditors | 79 | 78 |

| Farmers are implementing activities to reduce debt and/or increase revenue | Per cent of farmers implementing terms of their signed agreement | 90 | 92 |

| Creditors are suspending collection actions | Per cent of creditors who have suspended collection actions while the farmer implements the terms of their signed agreement | First Survey will establish a baseline | Not Available |

| Farmers are advancing their personal and business goals | Per cent of producers with an improved financial situation | 78 | 78 |

| Farmers are advancing their personal and business goals | Per cent of producers with reduced risk and credit problems | 100 | 78 |

| Creditors are achieving greater returns than they would have through collection action | Per cent of creditors with lower costs of debt recovery as a result of FDMS | 57 | Not Available |

| Creditors are achieving greater returns than they would have through collection action | Per cent of creditors with increased recovery of debt as a result of FDMS | 30 | 11 |

| AAFC: FDMS Program Performance Measurement and Risk Management Strategy (PPMRMS) | |||

According to the review of administrative data, almost four-fifths (79%) of cases proceed through the mediation process and are concluded (see Table 4.5). As highlighted in Table 4.4, of those files that are completed, the majority (78%) involve a signed agreement between the farmer and creditor that details a repayment schedule and/or other next steps. Of those producers who did reach a signed agreement, most (92%) reported that they fulfilled the terms of the mediation agreement.

| Status of Case | Count | Per cent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Completed – Arrangement Signed | 1,645 | 61.3 |

| Completed – No Arrangement Signed | 474 | 17.7 |

| Terminated – No Arrangement | 91 | 3.4 |

| Withdrawn | 271 | 10.1 |

| Received | 1 | 0.0 |

| Rejected | 203 | 7.6 |

| Total | 2,685 | 100.0 |

| Source: AAFC FDMS administrative data (computed from status at admission, file closure code, and file closure result), August 1, 2008 to September 20, 2014 | ||

Examination of administrative data provides insight into the typical outcomes associated with completed agreements. As highlighted in Figure 6, the most common outcome specified in the agreement was the restructuring of debt (46%). In some instances, producers and creditors were able to negotiate a satisfactory exit arrangement (i.e. an informal agreementFootnote 20) in which a portion of the debt or loan could be reduced subject to other repayment terms (21%). Bankruptcy proceedings were identified as the outcome in only 0.3% of cases.

Description - Figure 6

| Type | Per cent (%) |

|---|---|

| Restructuring Debt | 46.1 |

| Satisfactory Exit Arrangement | 21.4 |

| Dispose of Some Assets | 15.3 |

| Sale of Asset/Restructure Debt | 6.9 |

| Mgmt. Changes/Sale Asset | 4.3 |

| Management Changes | 0.9 |

| Mgmt. Changes/Restructure Management | 0.9 |

| No Change | 0.8 |

| Obtain Off-Farm Employment | 0.8 |

| Bankruptcy | 0.3 |

| Other | 2.5 |

Source: AAFC FDMS administrative data

According to the evaluation survey, producers feel that the FDMS helps them to advance their personal and business goals. The majority of producers reported that as a result of their participation in the FDMS their debt was now more manageable (78%) and that their overall financial situation had improved (74%).

Creditors were asked in the survey about how the FDMS affected their bottom line in terms of the amount they received from a farmer's outstanding debt. The majority of creditors (70%) reported that they received the same amount or more when they participated in the FDMS as when they did not; however, almost a third of creditors (30%) reported that they received less. Although it is voluntary for creditors to participate in FDMS, the fact that a third of creditors indicated that they received less is likely a strong indicator of why creditors had a more negative opinion of the FDMS program overall (as reported by the survey). It would be beneficial for the program to continue to monitor the views of creditors as their participation in the FDMS is critical to its success.

4.2.4 End outcomes

The farmer from case study three believed that without the FDMS, he/she would have had their loan called. This would have resulted in difficulties obtaining future capital, and may have resulted in significant repayment challenges.

The indicators associated with the FDMS's end outcome, i.e., the number of bankruptcies for the agriculture sector and the per cent of farms with high free cash flow, are not appropriate indicators for measuring the achievement of the FDMS's end outcome - increased sector resilience. The FDMS does not have influence on the number of bankruptcies in the agriculture sector and the per cent of farms with high free cash flow, when compared over a specific period of time. Rather, a myriad of other interrelated factors (commodity prices, interest rates, farm composition, etc.) are much more important, some of which were discussed in section 3.1.1. For example, during an economic recession, it is likely that bankruptcies in the agriculture sector will increase, but this would have nothing to do with the FDMS. That said, the number of bankruptcies that the FDMS has prevented is an important indicator of success (as discussed below), as the FDMS contributesFootnote 21 to this result.

The evaluation found that the activities of the FDMS have contributed to the achievement of the program end outcome, namely increased sector resilience. For example, over the evaluation period, the vast majority (86%) of producers applied to the program only once, i.e. most producers who participated in the program have not needed to access it again in the future. This could suggest that producers who have participated in the FDMS once may be less likely to require further intervention later, thereby increasing the sector's resilience. Most (88%) producers surveyed also reported that they did not have to renegotiate a loan that had been part of a FDMS mediation agreement.

Even though the farmer from case study number four lost their operation, they were very satisfied with the agreement and fulfilled its conditions. The farmer believed that they would have lost the farm anyway without the FDMS.

The survey results suggest that the FDMS has had a major impact in terms of assisting producers to maintain their farm operations. Half of producers noted that participation in the FDMS helped prevent loan defaults, and a similar proportion noted that participation in the program allowed them to continue to operate their farm (56%). The program has had success in terms of assisting producers to avoid bankruptcy, as 41 per cent stated that they would have likely declared bankruptcy in the absence of any assistance from the FDMS.

Creditors are divided on the long-term effects of the FDMS on producers' financial situations. Roughly half (49%) stated that producers were just as likely to default on future payments, while the other half (51%) viewed farmers as being less likely to default on future payments. Financial consultants and mediators had a more positive view than creditors on the end outcomes of producers who have participated in the FDMS. Almost all (90.9%) financial consultants and mediators reported that producers that go through the FDMS are less likely to default on future payments.

4.3 Performance – efficiency and economy

The evaluation assessed the extent to which the FDMS is being operated in an efficient and economical manner.

The FDMS is currently meeting its services standards (see Table 4.6 below).

| Service Standard | Indicator | Target (%) | Actual (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAFC Program Management and Oversight | Per cent of client inquiries responded to by end of next business day | 80 | 98 |

| AAFC Program Management and Oversight | Per cent of application that were notified as being accepted or not by end of next business day. | 80 | 99 |

| Mediation | Per cent of cases where all necessary documentation was sent to creditors and producers 7 business days prior to the mediation meeting. | 80 | 99 |

| Mediation | Per cent of mediation meetings scheduled within 70 calendar days after acceptance of the application | 80 | 83 |

| AAFC: FDMS Program Data | |||

In terms of program efficiency, although the decrease in demand for the program has resulted in an increase in costs per participant, the restructuring of the program in 2012 has helped to reduce overall costs. The total cost of the FDMS program between 2008-09 and 2013-14 fiscal years was $21.2 million (see Table 4.7). Over this period 2,390Footnote 22 producers participated in the program, resulting in an average cost of $8,854.87 per application. Two-fifths of program expenditures are for the salary of program staff, while the remaining three-fifths are spent on non-pay operating expenditures, which primarily involve the cost of contracting financial consultants and mediators.

As Table 4.7 demonstrates, the cost per approved application has increased each year since 2008-09. This has been due to the decline in the number of applications (i.e. loss of economies of scale) rather than due to increased costs to manage the FDMS as seen by the decrease in operating expenditures each year since 2009-10. It must be noted, however, that as the FDMS is legislated and thus obligated to respond to demand, an analysis of cost per participant must be viewed within the context that demand for the program could rise in the future and that the program needs be prepared to meet this potential demand.

(2008-2009 to 2013-2014)

| Operating Expenditures1 | Approved Applications2 | Operating Expenditures per Approved Application | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Salary ($) | Non-Pay Operating ($) | Total ($) | Count | Salary ($) | Non-Pay Operating ($) | Total ($) |

| 2008/09 | 1,184,704 | 1,888,320 | 3,073,025 | 403 | 2,939.71 | 4,685.66 | 7,625.37 |

| 2009/10 | 1,428,522 | 3,025,240 | 4,453,762 | 535 | 2,670.13 | 5,654.65 | 8,324.79 |

| 2010/11 | 1,444,346 | 2,837,709 | 4,282,056 | 476 | 3,034.34 | 5,961.57 | 8,995.92 |

| 2011/12 | 1,387,365 | 2,322,635 | 3,710,000 | 387 | 3,584.92 | 6,001.64 | 9,586.56 |

| 2012/13 | 1,329,284 | 1,643,297 | 2,972,581 | 306 | 4,344.07 | 5,370.25 | 9,714.32 |

| 2013/14 | 1,072,305 | 1,599,421 | 2,671,726 | 283 | 3,789.06 | 5,651.66 | 9,440.73 |

| Total | 7,846,526 | 13,316,622 | 21,163,150 | 2,390 | 3,283.07 | 5,571.81 | 8,854.87 |

| Source: AAFC Program Data, FDMS Financial Data Note: 1 Excludes Workforce Adjustments to Salary and non-pay operating 2 Excludes applications that were rejected. |

|||||||

4.4 Design and delivery

The evaluation found that program outcomes would be enhanced if producers approached the FDMS earlier and if the program provided follow-up once an agreement had been reached. These conclusions were also found in the 2011 Report to Parliament on the Farm Debt Mediation Act. Interviewees frequently indicated that too few producers are applying to the program early enough to be able to explore options apart from selling assets or possibly selling their farms. This is attributable in considerable part to a lack of awareness of the program among producers.

Survey results indicate that producers are typically not familiar with the FDMS. Producers primarily learn about the program from their creditors only once they are in severe financial difficulty at which point creditors are legally required to inform them of the option to participate in the FDMS. In fact, creditors who reported in the survey that the FDMS does not help producers in default situations tended to cite timing as the reason. By the time the case is with the FDMS, the debt for some producers is considered too severe for mediation to be useful. If producers were generally more aware of the program, they would be more likely to access the FDMS prior to finding themselves in severe financial difficulties.

Key informants also raised concerns over the lack of program follow-up once an agreement had been reached. While the mediation and advice given throughout the program is generally well-regarded, there is little to no contact with producers after an agreement is reached to ensure that they do not require additional support implementing their recovery plans. A follow-up may be useful, for example, for providing advice on what support services are available if the producer is facing difficulties implementing their agreement. A follow-up would also be helpful in future evaluations and legislative reviews as it would allow the program to collect important performance information on longer-term outcomes.

5.0 Evaluation conclusions

5.1 Relevance

The FDMS continues to provide a valuable service that complements other federal government agricultural programs. The agricultural sector is cyclical and therefore producers' demand for debt mediation services fluctuates based on the economic conditions facing Canada.

There are a number of factors that affect producers' control over the financial viability of their farm operations, many of which are unpredictable, such as weather and disease. As a valuable part of a larger suite of programs offered by AAFC to increase producers' business capacity and management of risk, the FDMS offers producers the opportunity to work with their creditors to come to a mutually acceptable agreement on their debt obligations.

The FDMS is a unique service that complements other federal and provincial programs and aligns with federal priorities and AAFC's strategic outcomes. The FDMS plays an important federal role as it provides consistency in policies and quality of services across Canada.

5.2 Performance – effectiveness

The FDMS is largely achieving its intended outputs and outcomes; however, creditors have somewhat mixed opinions with regard to the performance and impact of the program.

Program data and survey results indicate that the FDMS is having the desired impact on producers, and therefore, the program is achieving its intended results. Agreements are being signed, producers' financial situations are improving and there is evidence to show that participation in the FDMS is having a lasting impact on producers' personal and business goals.

The majority of creditors would recommend the program to producers and indicated that the FDMS serves as an effective source of communication between producers and creditors during difficult times. However, compared to producers and mediators/financial consultants, creditors were less satisfied with their participation in the FDMS. This could partially be explained by the fact that that 30 per cent of creditors believed that they received less money from the FDMS process than if they had not participated.

5.3 Performance – efficiency and economy

The FDMS has reduced overall costs to compensate for a decrease in demand.

The FDMS is meeting its service standards. In terms of program efficiency, although the decrease in demand for the program has resulted in an increase in costs per participant, the restructuring of the program in 2012 has helped to reduce overall costs. It must be noted, however, that as the FDMS is legislated and thus obligated to respond to demand, an analysis of cost per participant must be viewed within the context that demand for the program could rise in the future and that the program needs be prepared to meet this potential demand.

5.4 Design and delivery

The FDMS would be more effective if producers were more aware of the program, accessed it earlier and were provided with follow-up after an agreement was signed.

Key informants indicated that many producers are not applying to the program early enough to be able to explore options apart from selling assets or possibly selling their farms. Survey results indicate that producers are typically not familiar with the FDMS. Producers primarily learn about the program from their creditors only once they are in severe financial difficulty. Producers could potentially see more benefits from the FDMS if they became aware of and applied to the program earlier.

The evaluation also found that the FDMS would be more effective if follow-up was provided to producers after the agreement was signed. This would allow the program to provide assistance to producers who are having difficulties implementing their agreements and would also provide the opportunity for the program to collect important performance information to support evaluations and legislative reviews.

6.0 Issues and recommendations

The evaluation includes the following issues, recommendations and management response and action plans:

Issue 1

A common theme emerging from multiple lines of evidence for this evaluation concerns the fact that many producers are not aware of the FDMS and that many are applying to the program too late. The FDMS would be more effective if producers were made more aware of the program and accessed it as early as possible.

Recommendation

AAFC's Programs Branch should:

Examine the possibility for developing a strategy for increasing the overall awareness of the FDMS among producers and other stakeholders, and for communicating to the various stakeholders the importance of producers accessing the program as early as possible.

Management Response and Action Plan

Agreed: Currently, the Farm Debt Mediation Service budgets $90,000 per year towards advertising (approximately $65,000 for media buy and $25,000 for production). Programs Branch, in cooperation with Public Affairs Branch, will review the Farm Debt Mediation Service's current outreach and communications plan, to enhance its effectiveness. This will include exploring the potential to increase spending on communications efforts to increase farmer awareness of the Farm Debt Mediation Service, including the importance of early intervention.

Target date for Completion

April 1, 2017

Responsible Position

Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch and DG Business Development and Competitiveness Directorate, Programs Branch

Issue 2

Both survey and interview data reveal that producers would benefit from additional contact with the FDMS after the agreement has been signed. An additional follow-up would help determine whether the producer is making positive changes and improving his/her financial situation, or if further support is needed. It would also provide an opportunity to gather valuable data on the longer-term outcomes of the FDMS.

Recommendation

AAFC's Programs Branch should:

Examine the feasibility of including an additional follow-up between the producer and the FDMS after an agreement is signed.

Management Response and Action Plan

Agreed: In 2010, the Farm Debt Mediation Service investigated the possibility of undertaking additional follow-up work with Farm Debt Mediation Service clients and, after consulting Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Legal Services, it was determined that additional follow-up activities were beyond the scope and legislative mandate of the current Farm Debt Mediation Act.

That said, Programs Branch will undertake an investigation/survey to determine the level of interest by producers in additional follow-up work and then will explore the feasibility of expanding the program's authority, potentially under the next agricultural policy framework for 2018.

Target date for Completion

April 1, 2017

Responsible Position

Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch and DG Business Development and Competitiveness Directorate, Programs Branch

Annex A: Bibliography

- AAFC (2014). 2014-15 Report on Plans and Priorities. Accessed on July 2015.

- AAFC (2013). AAFC Report on Plans and Priorities 2013-2014.

- AAFC (2012). AAFC Report on Plans and Priorities 2012-2013.

- AAFC (2011). AAFC Report on Plans and Priorities 2011-2012.

- AAFC (2010). AAFC Report on Plans and Priorities 2010-2011.

- AAFC (2012). An Overview of the Canadian Agriculture and Agri-Food System.

- AAFC (February 2013). Canada's Farm Income Forecast for 2012 and 2013.

- AAFC (February 2012). Canada's Farm Income Forecast for 2011 and 2012.

- AAFC (2012). Departmental Performance Report 2011-2012.

- AAFC (2011). Departmental Performance Report 2010-2011.

- AAFC (2010). Departmental Performance Report 2009-2010.

- AAFC (2009). Departmental Performance Report 2008-2009.

- AAFC (2012). Farm Financial Program Branch Priorities 2012-2013.

- AAFC (2011). Farm Financial Program Branch Priorities 2011-2012.

- AAFC (2011). Farm Financial Program Branch Priorities 2010- 2011.

- AAFC (2009). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2008). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2007). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2006). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2005). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2004). Farm Financial Survey.

- AAFC (2009). Financial Situation and Performance of Canadian Farms, 2009.

- AAFC (2013). Medium Term Outlook for Canadian Agriculture International and Domestic

Markets. - AAFC (2012). Medium Term Outlook for Agriculture (2012-2021).

- AAFC (2013). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2013-2014.

- AAFC (2012). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2012-2013.

- AAFC (2011). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2011-2012.

- AAFC (2010). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2010-2011.

- AAFC (2009). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2009-2010.

- AAFC (2008). Report on Plans and Priorities. 2008-2009.