Alternate format

2021 Report to Parliament

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

December 2021

On this page

1. Introduction and background

The Farm Debt Mediation Service (FDMS) is a federal offering administered through Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). The FDMS is rooted in the Farm Debt Mediation Act (1997, c. 21), which came into force in 1998 as a replacement for the earlier Farm Debt Review Act (1986), which was a response to widespread financial difficulties experienced by farmers during the early 1980s. The FDMS aims to bring insolvent farmers and their creditor(s) together with a mediator in a neutral forum to reach a mutually acceptable solution. The FDMS is provided by the Government of Canada as a free, voluntary, and confidential service.

Section 28 of the Farm Debt Mediation Act (1997, c. 21) requires that the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food (AAFC) conduct a review every five years of the Farm Debt Mediation Service (FDMS) and submit to Parliament a report detailing the environmental context for the FDMS and findings of the review. In meeting the provisions of the Farm Debt Mediation Act, this review and report covers the fiscal years 2016–17 through 2020–21.

This review addresses topics related to the relevance and performance of the FDMS and identifies recommendations for improvements to the legislation and services. The review was completed between August and November 2021 and was based on three main lines of evidence:

- Review of FDMS documentation and data, including service usage over the past five years. Additional information available through Statistics Canada along with publicly available reports and materials examining the financial situation of farmers were also reviewed to clarify economic and sector trends driving need for the FDMS.

- Interviews with a total of 30 stakeholders, including 10 financial consultants and mediators, nine creditors, eight farmers, and three FDMS program officers. These interviews were based on semi-structured interview guides and lasted approximately 60 minutes.

- Surveys of farmers and creditors who had participated in the FDMS over the review period. In total, 210 farmer surveys and 162 creditor surveys were completed with farmers and creditors from across the country.

2. Perspective on Canada’s agriculture sector and farm economy during the review period

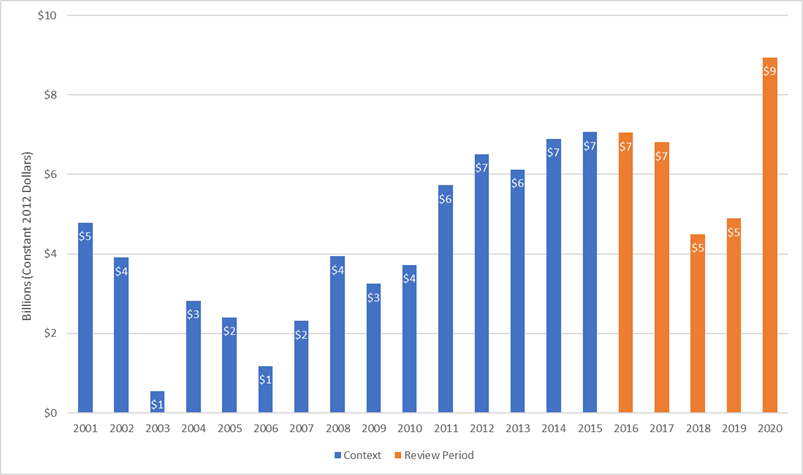

Canadian farmers experienced a generally sound financial position during the review period, with net income between 2016 and 2020 performing above the average of the past 20 years in real terms.Footnote 1 While 2018 and 2019 were weaker due to large increases in expenses like feed,Footnote 2 this was balanced by a strong year in 2020 driven by export demand for grains and oilseeds, as well as lower fuel and fertilizer prices.Footnote 3

Description of above image

| Year | 2012 constant dollars |

|---|---|

| Prior to review period | |

| 2001 | 4,783,370,656 |

| 2002 | 3,906,544,529 |

| 2003 | 549,589,901 |

| 2004 | 2,819,624,553 |

| 2005 | 2,403,316,763 |

| 2006 | 1,180,909,808 |

| 2007 | 2,312,755,459 |

| 2008 | 3,938,933,893 |

| 2009 | 3,246,789,474 |

| 2010 | 3,722,657,262 |

| 2011 | 5,730,465,587 |

| 2012 | 6,509,335,000 |

| 2013 | 6,126,846,608 |

| 2014 | 6,900,814,851 |

| 2015 | 7,066,980,545 |

| Review period | |

| 2016 | 7,051,787,645 |

| 2017 | 6,808,648,776 |

| 2018 | 4,501,209,991 |

| 2019 | 4,893,770,701 |

| 2020 | 8,943,448,556 |

Source: Statistics Canada Table 32-10-0052-01

Farm debt has been trending upward since 2014; in 2020, Canada’s total farm debt reached $116 billion. However, the agricultural sector’s debt-to-asset ratio and resulting interest payments remain below historical levels, as seen in Figure 2.2 below.

Description of above image

| Year | Debt-to-asset ratio | Interest payments (as a percentage of gross operating expenses) |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 0.17 | 8.71 |

| 2002 | 0.172 | 8.06 |

| 2003 | 0.179 | 7.84 |

| 2004 | 0.177 | 7.55 |

| 2005 | 0.173 | 7.59 |

| 2006 | 0.172 | 8.51 |

| 2007 | 0.169 | 8.90 |

| 2008 | 0.169 | 7.98 |

| 2009 | 0.172 | 6.62 |

| 2010 | 0.166 | 6.29 |

| 2011 | 0.162 | 6.04 |

| 2012 | 0.156 | 5.87 |

| 2013 | 0.155 | 6.00 |

| 2014 | 0.15 | 6.07 |

| 2015 | 0.151 | 5.95 |

| 2016 | 0.156 | 6.17 |

| 2017 | 0.155 | 6.39 |

| 2018 | 0.162 | 7.29 |

| 2019 | 0.168 | 7.89 |

| 2020 | 0.17 | 7.57 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 32-10-0056-01 and 32-10-0049-01

Despite the overall sound financial position of Canadian farms as a whole, farms’ average financial position varied considerably between provinces. British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, which together are home to nearly half of Canadian farms,Footnote 4 have particularly low levels of farm debt. Farms in Ontario, with represent approximately one quarter of the country’s farms, also fall slightly below the national average. Of greater concern, farms in Quebec and Atlantic Canada are close to a 0.30 debt-to-asset threshold which can be considered an indicator of high risk levels of debt.Footnote 5

Description of above image

| British Columbia | 0.137 |

|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | 0.138 |

| Alberta | 0.145 |

| Ontario | 0.169 |

| Canada | 0.17 |

| Manitoba | 0.193 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.255 |

| New Brunswick | 0.27 |

| Quebec | 0.273 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.296 |

| Newfoundland | 0.32 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 32-10-0056-01

These provincial differences in farm debt loads can be partially explained by the farm type composition of each province. Specifically, dairy cattle and milk production farms (which are common in Quebec) have much higher rates of debt than beef cattle and ranching farms (which are common in the West), which helps to explain why Quebec has higher debt levels than Alberta and Saskatchewan.Footnote 6Footnote 7 Low levels of farm debt in Saskatchewan and Alberta can also be explained by a healthy grain and oilseed sector.

The last year of the review period, 2020–21, coincided with disruption across the economy due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Agriculture was not immune to these disturbances, including labour shortages during harvest season (travel restrictions limited the use of temporary foreign workers) and supply chain breaks (such as temporary closures of food processing plants due to outbreaks).Footnote 8 Additionally, like other commodities, crop prices experienced a temporary slump at the beginning of the pandemic.Footnote 9

Generally, forecasts see a stable-to-positive future for Canadian agriculture, with demand expected to grow for the foods produced or processed in Canada, including seafood, organic and natural products, and non-meat proteins. However, several key challenges remain, including input prices, weather, and labour shortages. Perhaps most importantly, the sector’s financial situation may be threatened by higher interest rates that would impact the ability of farms to service their debt.Footnote 10 As such, the financial situation of farmers may remain sound for some time to come, although this is not true for all farms, and there remains a significant degree of variation between provinces and farm types.

3. Description and objectives of the Farm Debt Mediation Services

As mentioned above, the FDMS aims to bring producers and their creditor(s) together with a mediator in a neutral forum to reach a mutually acceptable solution. To be eligible for the FDMS, farmers must farm commercially and be unable to make their payments on time, have ceased making payments, or have debts exceeding the value of their property, if sold.

The FDMS is divided into two application streams under the Farm Debt Mediation Act. The first, Section 5(1)a, is available to farmers when they have been informed by a secured creditor that they have started or that they intend to start the process of collecting on debt. Under this stream, farmers are entitled to financial counselling, a financial review, and mediation. To allow time for that to occur, they also receive a stay of proceedings, which temporarily suspends recovery and seizure of assets for 30 calendar days (which can be extended in 30-day increments to a maximum of 120 calendar days).

The second stream, Section 5(1)b, is available to farmers who are struggling financially but have not yet been served with a notice of intent or other recovery action from their creditors. Under this stream, farmers are entitled to the financial counselling, financial review, and mediation, as with the first stream, but not the stay of proceedings.

Upon receipt of an application, an FDMS program officer screens the documentation to confirm it is complete and then assigns a mediator as well as a qualified financial consultant to work with the farmer throughout the mediation process. Next, the financial consultant meets with the farmer, conducts a site visit to inspect the assets, then prepares a detailed financial statement for the farm and assists the farmer in developing a recovery plan to be presented to creditors during the mediation.

Once the financial statement and recovery plan are developed, the mediator hosts a meeting between the farmer, financial consultant, and creditor(s). During the meeting, the mediator remains neutral and works to ensure a fair and unbiased mediation process. The mediator has no decision-making power. Their role is to assist the participants in reaching their own mutually acceptable settlement. The mediator leads the discussion, encouraging the producer and creditor(s) to engage with each other. The mediator helps the parties to communicate effectively and helps to explore and clarify options for settlement. When the parties agree upon a solution, the mediator draws-up an agreement, ensures it is signed by all three parties, and provides each with a signed copy.

4. The Farm Debt Mediation Service Activity Levels

During the review period, 2016–17 to 2020–2021, a total of 1,384 FDMS applications were received. The number of applications per year remained relatively stable throughout most of the review period. The 2020–21 year was the exception; applications fell by 13% from 312 the previous year to 230 (Figure 4.1).

Description of above image

| Year | Overall | 5(1)(a) | 5(1)(b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 | 285 | 178 | 107 |

| 2017-18 | 262 | 156 | 106 |

| 2018-19 | 295 | 170 | 125 |

| 2019-20 | 312 | 185 | 127 |

| 2020-21 | 230 | 148 | 82 |

That year witnessed the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which had substantial economic impacts.

For example, the Federal Government launched a number of programs to support both individuals and companies manage during the crisis, including the:

- Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB),

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS),

- Business Credit Availability Program (BCAP) Guarantee,

- Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA), and

- Mandatory Isolation Support for Temporary Foreign Workers Program.

In addition, the Government worked with financial institutions to ensure Canadians could access debt deferrals, including mortgage deferrals. For example, CMHC allowed lenders to offer deferred payments for insured mortgages during the pandemic.

It is currently unclear whether the decrease in applications for the 2020–21 year reflects such measures implemented in response to the pandemic or a decrease in need for the FDMS given that 2020 was a strong year for farm income, as seen in Figure 2.1 above.

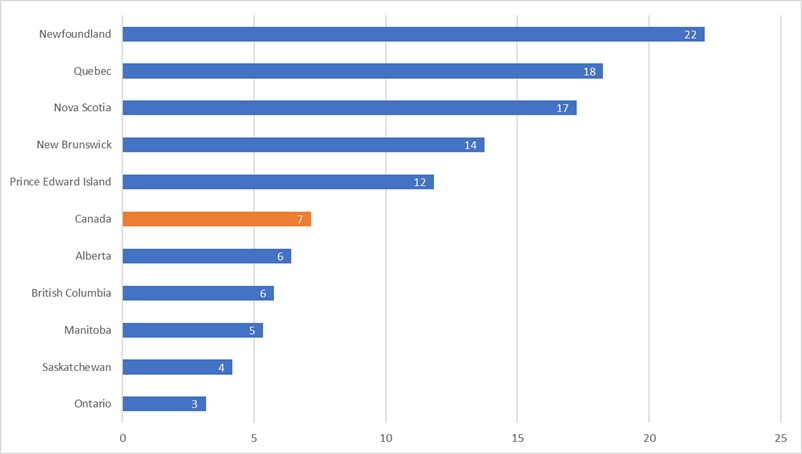

The five-year total of 1,384 FDMS applications received corresponds to a rate of approximately 7 applications per 1,000 farms, based on Canada’s 2016 total of 193,492 farms.Footnote 11 This application rate varied significantly between provinces (Figure 4.2), with FDMS application rates generally reflecting the provincial debt-to-asset ratios provided in Figure 2.3 above. Western Canada and Ontario have the lowest application rates, while Quebec and Atlantic Canada have higher rates of FDMS applications.

Source: Farm Debt Mediation Service data and Statistics Canada Table 32-10-0152-01

Description of above image

| 2016-17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | Total farms, 2016 | Total applications | Applications per 1,000 farms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Brunswick | 12 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2255 | 31 | 13.7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 407 | 9 | 22.1 |

| Nova Scotia | 16 | 10 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 3,478 | 60 | 17.3 |

| Ontario | 27 | 26 | 36 | 42 | 26 | 49,600 | 157 | 3.2 |

| Prince Edwards Island | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1353 | 16 | 11.8 |

| Quebec | 126 | 113 | 102 | 113 | 74 | 28,919 | 528 | 18.3 |

| East total | 187 | 157 | 165 | 174 | 118 | 86,012 | 801 | 9.3 |

| Alberta | 32 | 48 | 52 | 66 | 61 | 40,368 | 259 | 6.4 |

| British Columbia | 22 | 19 | 28 | 16 | 16 | 17,528 | 101 | 5.8 |

| Manitoba | 19 | 11 | 20 | 20 | 9 | 14,791 | 79 | 5.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 25 | 27 | 30 | 36 | 26 | 34,523 | 144 | 4.2 |

| West total | 98 | 105 | 130 | 138 | 112 | 107,210 | 583 | 5.4 |

| Canada total | 285 | 262 | 295 | 312 | 230 | 193,492 | 1384 | 7.2 |

Sources: Farm Debt Mediation Service data and Statistics Canada Table 32-10-0152-01

Of the 1,384 applications received, 73% or 1,016 resulted in a mediation meeting between the farmer and creditors. Of the 27% of applications that did not result in a mediation meeting, the majority (approximately 20%) either had an incomplete application, were ineligible or were withdrawn by the applicant while a few (about 6%) were terminated by the FDMS as required under section 14(2) of the FDMA for one of the following reasons:

- the majority of creditors or the farmer refuse to participate;

- the farmer contravened a directive, acted in bad faith or jeopardized assets;

- the farmer obstructed the guardian in the performance of his/her duties; or

- the mediation will not result in an arrangement.

During the review period, of the 1,016 mediation meetings that were held, 79% of those resulted in an agreement between the farmer and his/her creditors. When an agreement was reached, it was most common for farmers to restructure debt, sell assets, or dispose of some assets as part of the approved recovery plan (see Figure 4.3).

| 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restructure debt | 82 | 36 | 49 | 56 | 46 | 269 |

| Sale of asset/ restructure debt |

27 | 53 | 33 | 52 | 25 | 190 |

| No arrangement | 38 | 39 | 44 | 31 | 36 | 188 |

| Dispose of some assets | 18 | 23 | 34 | 31 | 16 | 122 |

| Satisfactory exit arrangement | 29 | 17 | 20 | 19 | 9 | 94 |

| Management changes/ restructure |

2 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 36 |

| No change | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 25 |

| Management changes/ sale of assets |

0 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 23 |

| Management changes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 14 |

| Bankruptcy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Obtain off-farm employment |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 47 |

| Total | 199 | 190 | 220 | 237 | 170 | 1,016 |

Source: Farm Debt Mediation Service data

5. Contribution of the Farm Debt Mediation Service to departmental priorities and to risk management in the agriculture sector

The FDMS aligns with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s mission to “provide leadership in the growth and development of a competitive, innovative, and sustainable Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector.” During the review, those interviewed reported that the FDMS supports that mission by providing mediation between insolvent farmers and their creditors (which in turn helps farmers overcome financial stresses and remain economically viable) and helps to repair relationships between farmers and their creditor(s). In addition, the services provide farmers with the opportunity to learn from a financial consultant, which may contribute to them being more financially stable, competitive, and innovative in the future.

AAFC’s Business Risk Management programs and services complement the FDMS. These programs include AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance, AgriRecovery, and Advanced Payments Program. Further, the Canadian Agricultural Partnership represents provincial, territorial, and federal government commitment to invest a combined $3 billion over five years (2018 to 2023) to strengthen and grow Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector.

6. Key findings from review of the Farm Debt Mediation Service — 2016–17 through 2020–21

In accordance with the Farm Debt Mediation Act, a review of the Farm Debt Mediation Service (FDMS) covering the fiscal years 2016–17 through 2020–21 was conducted to support this Report to Parliament. The review assessed the relevance and performance of the FDMS and sought feedback from beneficiaries and stakeholders of the services.

Overall, the review revealed that the FDMS is a valuable, unique, and necessary service. Farmers and creditors reported numerous benefits of the services, alongside some challenges. Stakeholders explained that the FDMS benefits not just the farmers and creditors directly involved but also strengthens their local communities and the broader agricultural sector.

Most farmers and creditors reported positive experiences with the FDMS and positive outcomes arising from their participation. Farmers (85%) and creditors (65%) indicated that they would recommend the FDMS to others in a similar situation. They also reported high levels of satisfaction, with 74% of farmers and 62% of creditors reporting being satisfied with the overall quality of services delivered by the FDMS.

Farmers described benefitting from the stay of proceedings, which provided them the time to get their affairs in order and to plan for dealing with outstanding debt. They also explained how consultation with a financial expert helped them better understand their financial situation and, in many cases, enhanced their ability to manage and plan their business in the future.

Following mediation, most farmers reported that they fully implemented (57%) or partially implemented (24%) the agreements reached during mediation, which helped to reduce their debt and improve their financial situation. The majority of farmers (67%) reported being in a better financial situation after mediation compared to before, having a better understanding of their financial situation (67%), and reported that as a result of the services received through the FDMS they were able to make better business decisions (57%).

Creditors attested to the advantages of the mediation process for providing them with information and clarity on their client’s financial situation (50%), and in a majority of cases (77%) for helping them recover outstanding debt. Nearly one-half (44%) of creditors indicated that the FDMS produced more favourable results than typical methods of debt recovery, either recovering more money (15%) or saving on legal costs (29%). About one-third (33%) reported similar results from the FDMS compared to other debt collection methods. Finally, 23% reported worse results, recovering a lower amount of the outstanding debt compared to typical collection methods. Creditors reported that most but not all agreements are implemented by farmers following mediation, which aligns with reports from farmers.

The FDMS is widely seen as effective and efficient in delivering mediation services and in adapting to change, with stakeholders praising the FDMS as flexible and relevant for different types of farmers and financial challenges. However, a key concern raised was farmers’ limited and untimely awareness of the FDMS. Stakeholders consistently expressed that farmers learn about and apply to the FDMS too late in their financial difficulties, which makes financial recovery less likely. Less commonly, some farmers and creditors felt that mediation was biased in favour of the other party, and a small number of farmers raised concerns about creditors unfairly sharing their personal or financial information collected by the FDMS with members of their community.

In interviews, farmers, creditors, and other stakeholders reported some challenges with the fact that the mandate of the Farm Debt Mediation Service ends once the mediation meeting has been held. Farmers reported that they could benefit from some limited ongoing support from a financial consultant to help them as they implement agreements. Creditors similarly reported that farmers would be more likely to implement agreements if the FDMS supported ongoing interaction between the farmer and creditor and/or if the FDMS had more authority to enforce the implementation of agreements. Farmers were also likely to want advice from a business consultant or agrologist, in additional to the financial advice provided by the financial consultant. Some farmers reported feeling overwhelmed suggesting that mental health support or resources may be a gap in services.

An additional challenge noted by some stakeholders related to communication and the use of teleconferencing and videoconferencing software to host mediation meetings. Stakeholders noted that the FDMS has been working to improve digital communication and utilize video conferencing technology to support mediation meetings where possible but noted some technical challenges related to individual comfort with videoconference software and limited internet capacity in some areas.

Finally, some creditors suggested that the format of mediation meetings could be improved. Some creditors reported frustration with having to attend lengthy mediation meetings and wait for their turn to discuss the proposed agreement with their client and the mediator. Participants are encouraged by the FDMS to attend the full meeting to ensure they witness and understand all the discussions related to options and scenarios considered during the negotiations.

Some farmers (40%) who responded to the survey perceived some service gaps. Small proportions of farmers who responded to the survey indicated that the FDMS should consider offering the following complementary services: post-mediation financial advising services (21%), continued support from a financial consultant (21%), someone to act as a liaison between the farmer and creditor following mediation (21%), and/or mental health support or resources (17%).

Based on the feedback received during the review process, in the coming years, the FDMS will work towards:

- improving awareness of the FDMS, especially reaching farmers earlier in their financial difficulties, for instance through their creditors.

- exploring options to offer post-mediation services and/or to increase the authority of the FDMS to further assist farmers and creditors in implementing agreements.

- continuing to implement digital communication and videoconferencing where possible.

- better communicating privacy expectations and obligations under the FDMA to creditors so they do not share farmers’ financial information outside the mediation process.

- continuing to improve service delivery such as exploring whether the format of mediation meetings could be improved to make the process more efficient, clarifying the role of the financial expert to farmers and creditors and providing workshops and training sessions to FDMS staff, experts and mediators to assist them in their role.

- exploring the addition of business advising services to complement financial counselling and access to mental health services (such as access to counselling and/or social workers) during and/or post-mediation.

7. Next steps and next report

The FDMS is a well-established service that has a demonstrated need. The services align with AAFC’s mission and priorities to support growth and development if Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sectors.

As provided for by the Farm Debt Mediation Act, the Minister will next report to Parliament on the Farm Debt Mediation Act in five years’ time.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Realized net income is net cash income plus income in kind (for example, home-consumed products) minus operating expenses and depreciation.

- Footnote 2

-

“Farm income, 2018”. Statistics Canada. Available at www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190528/dq190528a-eng.htm

- Footnote 3

-

“Farm income, 2020”. Statistics Canada. Available at www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210526/dq210526b-eng.htm

- Footnote 4

-

“Number and Area of Census Farms, Canada and the Provinces”. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Available at www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/stats/census/number.htm

- Footnote 5

-

“Financial Performance of Agriculture 2019”. Government of Manitoba. Available at gov.mb.ca/agriculture/markets-and-statistics/economic-analysis/pubs/manitoba-analytics-financial-performance-of-agriculture.pdf

- Footnote 6

-

“Farm financial survey, financial structure by farm type, average per farm”. Statistics Canada. Available at www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3210010201

- Footnote 7

-

“Farms, by farm type and by province, 2011”. Statistics Canada. Available at www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2012000/chap/ag/tbl/tbl07-eng.htm

- Footnote 8

-

“COVID-19: Canada’s Agri-Food Sector Yields Strong Results Despite Pandemic”. EDC Economics. Available at edc.ca/content/dam/edc/en/premium/guide/covid-19-agriculture-sector.pdf

- Footnote 9

-

“Canada’s Agriculture Sector Bucking the Trend Seen Elsewhere in the Economy”. TD Economics. Available at economics.td.com/domains/economics.td.com/documents/reports/oa/CanadianAgricultureOutlook_2020.pdf

- Footnote 10

-

“Farm debt under control, but watch for higher interest rates: FCC chief economist”. Farm Credit Canada. Available at fcc-fac.ca/en/about-fcc/media-centre/news-releases/2021/farm-debt-under-control.html

- Footnote 11

-

“Number and area of farms and farmland area by tenure, historical data”. Statistics Canada. Available at www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3210015201