On this page

Abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQI+

-

Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and additional sexually and gender diverse people

- AAFC

-

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- GBA

-

Gender-Based Analysis

- LFIF

-

Local Food Infrastructure Fund

- NGO

-

Nongovernmental organization

- OAE

-

Office of Audit and Evaluation

Executive summary

Purpose

The Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE) of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) conducted an evaluation of the Local Food Infrastructure Fund (LFIF) to assess its relevance, design, delivery, efficiency and effectiveness.

Scope and methodology

Program activities for fiscal year 2019-20 to 2022-23 were evaluated using multiple lines of evidence: a review of documents, files and literature; an environmental scan; analysis of secondary and administrative data; interviews with internal and external stakeholders; and case studies. Activities out of scope for this evaluation include the Program’s activities during LFIF-3, which were included in a performance audit by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. The evaluation is considered formative, since the Program is currently being delivered by AAFC. The evaluation covers $32 million in AAFC grants and contributions.

Background

The LFIF is included under the Government of Canada’s Food Policy for Canada and is associated with AAFC’s domestic and international markets core responsibility. The Program provides funding to organizations to purchase food-related infrastructure to increase their capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food (immediate outcome); increase the availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food (intermediate outcome); and reduce household food insecurity in recipient communities (ultimate outcome). Launched in 2019, the LFIF is considered a new social policy program.

Findings

- The LFIF is aligned with federal and departmental priorities and the Food Policy for Canada; however, there was limited evidence demonstrating that the Program is aligned with its associated core responsibility, domestic and international markets.

- The Program is relevant insofar as it partially fills a gap in food security infrastructure funding while also duplicating some aspects of existing programs.

- The Program’s design is effective in supporting community food security outcomes rather than the stated ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity.

- Suitable indicators are used to understand the Program’s effects from the perspective of recipients; however, performance assessment is limited by a lack of external validation and indicators regarding nutrition and Gender-based analysis (GBA) plus.

- The Program made progress toward achieving its immediate and intermediate outcomes. Limited to no evidence demonstrated progress toward the ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity.

- Overall, the Program successfully reached its target groups and accessibility for Indigenous communities improved; however, potential recipients lack awareness of the Program leading to varying degrees of participation among LFIF’s target groups.

- Overall, the Program is administered efficiently.

Conclusion

The LFIF is aligned with priorities in the Food Policy for Canada, AAFC Mandate Letters, Treasury Board documentation and federal budgets to support access to food, Indigenous food systems and food security. While the Program is intended to be aligned with AAFC’s domestic and international markets core responsibility, no evidence suggested that the Program directly supports the sector’s competitiveness at home or abroad, exports, market access or international agricultural interests (each of which are fundamental components of the responsibility).

The LFIF’s ultimate outcome is reduced household food insecurity. However, the LFIF enables activities at the community level which strengthens food systems, particularly through funding infrastructure which supports increasing access to food. The LFIF does not address several factors that are critical for reducing household food insecurity, namely income support and supplementation, which is the mandate of other federal departments. Still, the Program’s broad range of eligible infrastructure types, beneficiary groups and its national scope fills gaps in community food security programming in provinces and territories where no such funding exists.

The Program has effective indicators in place to understand the LFIF’s effects from the perspective of recipients. For example, final project reports provide recipients the opportunity to report on demographic groups that were served and changes resulting from their respective projects. However, the evaluation also found a lack of data and information that is needed to validate results, assess progress toward outcomes and complete GBA Plus.

The Program made progress toward achieving its immediate and intermediate outcomes; however, there was little evidence to suggest that the ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity was achieved. Overall, the Program successfully reached its target groups and accessibility improved for some populations, such as Indigenous beneficiaries. A lack of program awareness was a contributing factor which led to an uneven distribution of benefits among LFIF’s beneficiary groups.

The Program is administered efficiently. Despite increased demands placed on the program area because of the Covid-19 pandemic, operational efficiency improved during the evaluation’s reference period. Recipients reported an increase in the value of food distributed after installing infrastructure, and investments in projects resulted in secondary benefits for individuals and communities.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy Branch, in consultation with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Management Branch, define AAFC’s role with supporting food security to inform potential changes to the Department’s core responsibilities.

Recommendation 2: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch adjust the Program’s ultimate outcome to better reflect its community food security design.

Recommendation 3: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch address opportunities to validate and improve program performance data to understand: achievement of community food security outcomes; differentiated impacts on target groups (GBA Plus); and cost-efficiency.

Recommendation 4: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch examine past design changes and outreach activities to inform future efforts to increase access for the Program’s priority populations.

Management response and action plan

Management agrees with the evaluation recommendations and has developed an action plan to address them by March, 2024.

1.0 Introduction

The OAE at AAFC conducted an evaluation of the LFIF as part of the 2022-23 to 2026-27 Office of Audit and Evaluation Plan. The evaluation complies with the Treasury Board of Canada’s Policy on Results. Findings from this evaluation are intended to inform current and future program and policy decisions.

2.0 Scope and methodology

The evaluation assessed the relevance, design, delivery, efficiency and effectiveness of LFIF activities from fiscal year 2019-20 to 2022-23. This includes LFIF1, 2, 4 and 5. Activities associated with program funding in 2019-20 (LFIF-3) were out of scope since this funding was included in a performance audit by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence including: interviews with Program applicants who received funding, applicants who did not receive funding, AAFC officials and external subject matter experts (researchers and academics); document reviews; peer-reviewed literature reviews; environmental scans; administrative and secondary data analyses; and 5 case studies.

The case studies focused on:

- projects where people with a low income were identified as an ultimate beneficiary

- projects where Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and additional sexually and gender diverse people (2SLGBTQI+) people were identified as an ultimate beneficiary

- projects where Indigenous People were identified as an ultimate beneficiary (and projects in the Territories)

- Program effects on increasing organizational capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food

- Program effects on improving the availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food

Throughout the evaluation process, early substantive findings were shared with AAFC management and staff involved in the Program.

The evaluation was limited in its examination of the Program’s outcomes due to the nature of the data collected from funding recipients. For the detailed evaluation methodology and associated limitations see Annex A.

3.0 Program profile

3.1 Overview of the Local Food Infrastructure Fund

The Program falls under the Food Policy for Canada. The Policy aims to ensure that “all people in Canada are able to access a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious, and culturally diverse food.” The LFIF, through its Performance Information Profile, is also associated with AAFC’s domestic and international markets core responsibility and the departmental result of “the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector contributes to growing the economy.” The domestic and international markets responsibility commits AAFC to provide programs and services to support the sector’s competitiveness at home and abroad. This is accomplished by:

- increasing opportunities for the sector to export its products

- maintaining and expanding market access

- advancing agricultural interests internationally

The LFIF supports community centres, food banks, not-for-profit organizations, Indigenous groups as well as regional and municipal governments to purchase infrastructure including food preparation and transportation equipment, technology, and energy and irrigation systems. Organizations including Indigenous groups, municipal governments and not-for-profit organizations are eligible to apply to the ProgramEndnote 1. LFIF is one of AAFC’s first social policy programs which supports new types of recipients and at-risk populations (compared to more “traditional” agriculture and agri-food sector stakeholders):

- Indigenous People

- people who are homeless or street-involved

- people from low-income households and/or isolated, rural or Northern communities

- persons with disabilities

- groups with social or employment barriers

- newcomers to Canada (including refugees)

- visible minorities

- women

- youth

- low-income seniors

- 2SLGBTQI+ people

- official language minority communities

The total project funding amount and the cost-share ratio between AAFC and the applicant for each stream of the LFIF is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Project funding amounts and cost-share ratio

| Fiscal year | LFIF stream | Total project funding ($) | Cost-share ratio for AAFC (%) | Cost-share ratio for Applicant or Project partner (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-20 | 1 | 5,000 to 25,000 | 50 | 50 |

| 2020-21 to 2021-22 | 2 | 5,000 to 250,000 | 85 | 15 |

| 2021-22 | 4Note 1 | 15,000 to 100,000 | 100 | 0 |

| 2022-23 to 2023-24 | 5 | 100,000 to 500,000 | 75 | 25 |

|

Notes LFIF-3 is not included in the table as this stream was reviewed by the Auditor General of Canada and subsequently excluded from the evaluation.

Source: Applicant Guides (LFIF-1, -2, -4 and -5) |

||||

Projects eligible for funding include, for example:

- community gardens and greenhouses

- kitchen and dining area renovations and equipment

- tractors and refrigerated and non-refrigerated vehicles

- walk-in refrigerators and freezers

- solar powered greenhouses

- water storage and irrigation systems for community gardens

3.2 Governance

The Program was authorized by Treasury Board and is administered by AAFC with Terms and Conditions and a Performance Information Profile containing responsibilities for data collection and measurement. The Food Programs and Challenges Division in the Innovation Programs Directorate in Programs Branch at AAFC, with support from the Financial, Performance and Data Analysis Division, is responsible for receiving and reviewing applications, developing and monitoring agreements, administering funds, measuring program performance and closing out projects (for example, receiving and analyzing final performance reports from funding recipients). Program promotion is shared between AAFC’s Public Affairs Branch and Programs Branch. Public Affairs Branch provides support for the general promotion of the Program, primarily through news releases, social media and newsletters, while Programs Branch delivers information sessions with potential applicants and responds to requests from organizations.

3.3 Resources

Actual expenditures for the Program from fiscal year 2019-20 to 2021-22 were $36,846,284, presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Program expenditures by fiscal year, 2019-20 to 2022-23

| 2019/20 Actual expenditures | 2020/21 Actual expenditures | 2021/22 Actual expenditures | 2022/23 Actual expenditures | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary ($) | 332,219 | 1,219,945 | 2,216,203 | not finalized | 3,768,367 |

| Employee Benefit Plan ($) | 49,168 | 180,552 | 332,430 | not finalized | 562,151 |

| Non-Pay Operating ($) | 4,895 | 164,353 | 151,205 | not finalized | 320,452 |

| Grants and Contributions ($) | 869,541 | 11,056,921 | 20,268,851 | not finalized | 32,195,313 |

| Total ($) | 1,255,823 | 12,621,771 | 22,968,690 | not finalized | 36,846,284 |

| Full-time equivalent staff | 4 | 14 | 25 | not finalized | n/a |

|

Source: Estimates and External Reporting Section, AAFC (August 22, 2022) |

|||||

3.4 Intended outcomes

The evaluation examined the Program’s immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes as described in the Performance Information Profile:

- Immediate outcome: Organizations have increased capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food in communities with projects supported by the Fund.

- Intermediate outcome: Increased availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food to constituents of communities with projects supported by the Fund.

- Ultimate outcome: Reduced household food insecurity in recipient communities.

4.0 Relevance

This section summarizes evaluation findings on the relevance of the Program; specifically, alignment with departmental and government priorities and responsibilities; identification of needs; whether there is a gap in programming and the extent to which the Program responds to this gap.

4.1 Alignment with priorities, roles and responsibilities

The LFIF is aligned with federal and departmental priorities and the Food Policy for Canada; however, there was limited evidence demonstrating that the Program is aligned with its associated core responsibility, domestic and international markets.

The LFIF aims to strengthen food systems and improve food security by providing funding to organizations to purchase infrastructure to increase food access and availability among groups at risk of food insecurity. The Program is intended to be aligned with AAFC’s domestic and international markets core responsibility.

The document and file review showed that the Government of Canada has made infrastructure investment for economic recovery and longer-term sustainability a priority. Addressing food security, community building and support for disadvantaged populations are also federal priorities and AAFC is mandated to help communities access healthy food. Several AAFC and Food Policy for Canada commitments have focused on supporting food security, specifically among northern and Indigenous communities. All of these commitments and mandates are reflected in the Program’s design and the outcomes of LFIF projects.

AAFC’s domestic and international markets responsibility relates to supporting the sector’s competitiveness at home or abroad, exports, market access and international agricultural interests. Aside from project adjudication guidelines which require that the local economic benefits of projects be considered when assessing applications, there was little evidence that the LFIF contributes to domestic or international markets. However, while food security is not clearly reflected in AAFC’s core responsibilities, multiple lines of evidence confirmed that AAFC directly and indirectly supports food security through policies, programs and initiatives to:

- increase agricultural productivity and therefore food production

- respond to natural disasters, which can mitigate disruptions to food production

- improve market access to support optimal trade agreements so that food can enter new markets

- enhance food safety, particularly during production and processing

- support farmers to produce nutrient-rich crops as a means to provide consumers with nutritious and healthy food

As such, AAFC has a less direct role with alleviating the main food security barriers faced by Canadians; income support and supplementation programs are not included in AAFC’s portfolio, but are addressed by other federal departments. In summary, the LFIF’s food security focus is relevant to the Department’s lines of business but is not clearly aligned with its core responsibilities.

4.2 Continued need for the Local Food Infrastructure Fund

The LFIF responds to community needs and partially fills a gap in food security infrastructure funding while also duplicating some aspects of existing programs.

The literature and interviews with subject matter experts made an important distinction between household food insecurity and community food security. While household food insecurity is closely tied to income and poverty (and requires changing socioeconomic conditions to increase food security), community food security adopts a “systems-perspective” on the availability, stability, safety, nutritional value and access to food at the community level through investments in physical and social infrastructure. For example, this includes:

- support for partnerships between different parts of the food system

- food education programs

- community gardens

- technology and equipment necessary for increasing access to and production, preservation and distribution of culturally-acceptable and nutritious food

Nongovernmental organizations (NGO), research centres and peer-reviewed literature reported that there is a need for infrastructure funding to support community food security in Canada. Academics, advocates and community leaders have stated that funding for infrastructure, such as, but not limited to, greenhouses, refrigeration systems and food processing equipment, is needed to improve food security, particularly in rural and remote areas. Most interviewed recipients (82%), when asked, said the Program was filling gaps in infrastructure programming for their communities. According to recipients, the most important infrastructure need for their organization was additional storage for food, including refrigeration capacity.

While recipients who were interviewed were unaware of similar supports for local food infrastructure in Canada, a scan of food security programs delivered by the federal government; provincial, territorial and municipal governments; and the not-for-profit and private sectors found that the LFIF is duplicating some elements of existing programs (primarily projects that are eligible for funding). However, most of these programs fund infrastructure projects on an ad-hoc basis or are limited to a specific demographic group or region.

Therefore, the LFIF fills a gap in the ecosystem of food security programming through its explicit focus on funding only infrastructure projects, its eligibility criteria (for example, types of infrastructure available for funding, and projects that must benefit at least one of 13 disadvantaged groups) and by its national scope (which includes all regions of Canada). The evaluation found that, aside from the LFIF, there is no other program in Canada which has the same combination of features. However, the evaluation also identified an absence of routine environmental scans which could help to ensure that the LFIF continues to strategically fill gaps and avoid duplication.

5.0 Program design and delivery

This section summarizes evaluation findings on the design and delivery of the LFIF which includes assessments of the Program and community food security theory; activities to promote and increase awareness of the Program; participation rates; and funding for target groups.

5.1 Community food security design

The Program’s design is effective in supporting community food security outcomes rather than the stated ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity.

The ultimate outcome of the Program is to reduce household food insecurity in recipient communities. Analysis of the literature, documents and interviews with academics articulated a causal relationship between lack of income and household food insecurity. To reduce household food insecurity requires ensuring that households have enough income to purchase food and basic necessities. Since the Program is designed primarily to support food systems, as opposed to improving participants’ economic circumstances, it is better positioned to increase food security at the community level rather than at the household level.

AAFC officials and subject matter experts who reviewed the Program’s design reiterated that the Program was not positioned to improve food security at the household level in any substantial way, because the LFIF does not fund projects associated with income (income support and supplementation are addressed by other federal departments). This point was further elaborated in the peer-reviewed literature: increasing household food security requires a substantial investment and changes to beneficiaries’ socioeconomic conditions.

The review of the Program’s Treasury Board submission, terms and conditions, guidelines and other foundational documents found that concepts associated with community food security are fully embedded in its design. ‘Food systems’, ‘access to food’, ‘availability of food’ and ‘community’ are reflected in Program documentation. Interviewed recipients identified that the most notable capacity change, as a result of their LFIF project, was the ability to grow, store and distribute more food to people in the community. The Program also funds food-related infrastructure and encourages partnerships between members of the food system, both of which are characteristics of community food security interventions. Finally, delivery elements, including consultations with communities to identify needs and requirements for recipients to partner with other organizations, further align the Program with community food security theory.

5.2 Accessibility and reach

Enhanced outreach activities with Indigenous organizations and Program eligibility changes during LFIF-5 increased Indigenous participation; however, access for other priority populations varied.

Promotion and awareness

The document and file review found that the Program was advertised primarily through social media, news releases, radio and in-person communication. There were approximately 35 activities implemented which targeted potential applicants (including meetings, news releases and social media). Program staff implemented a series of workshops with potential applicants to provide support with application processes. In total, over 450 individuals attended the workshops.

The evaluation found evidence of one communication activity that targeted a specific priority population. During LFIF-5, a communication plan to increase awareness among Indigenous organizations was implemented. This plan included distributing promotional material in Indigenous languages to over 95 Indigenous media outlets and meeting one-on-one with Indigenous organizations to explain application processes. Similar communication plans, targeted at other groups that experience high rates of food insecurity, were not planned or implemented.

The evaluation found that the absence of targeted outreach with other priority populations, such as non-Indigenous organizations, racialized groups and 2SLGBTQI+ communities, has contributed to varying degrees of participation among the LFIF’s targeted beneficiary groups. For example, one case study, which included a scan of 2SLGBTQI+ organizations in Canada, found that none had applied for LFIF funding. When interviewed, AAFC officials, subject matter experts, recipients and non-funded applicants all stated that organizations lacked awareness of the Program and that this contributed to reducing the Program’s accessibility.

Participation rates

LFIF-5 implemented design and delivery changes to improve accessibility for Indigenous organizations and rural municipalities. This included enhanced outreach activities and limiting eligible applicants to at least one of the following categories: located in rural community (population under 1,000) or small city (population between 1,000-29,999) or an Indigenous group (for example, Indigenous governments, communities or non-for-profit organizations).

This targeted outreach and narrowed eligibility criteria appears to have increased accessibility for Indigenous organizations and beneficiaries; Indigenous People were selected 35% more often as an intended beneficiary in LFIF-5 applications compared to LFIF-1, -2 and -4. Furthermore, Indigenous organizations submitted less than 20% of total applications throughout LFIF-1, -2 and -4 whereas in LFIF-5 they submitted 58% of total applications.

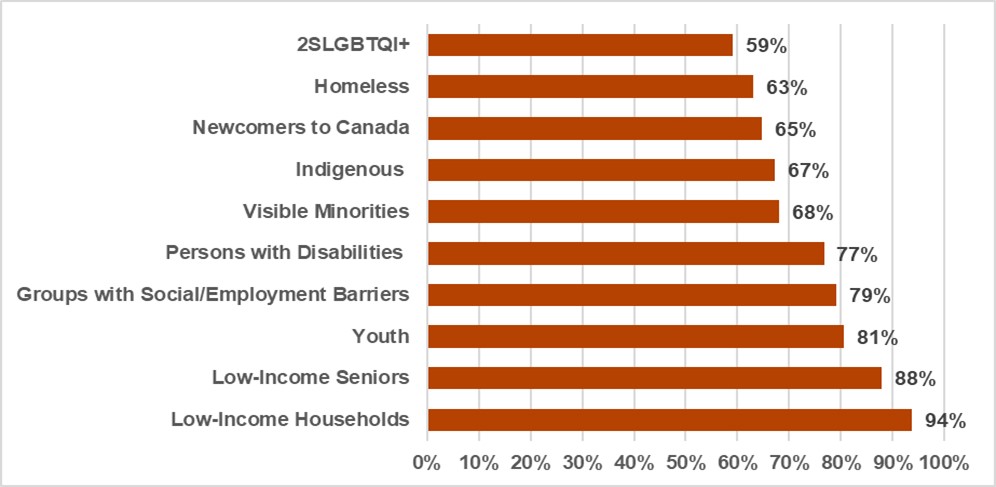

Analysis of final project reports showed that all priority populations were served by LFIF projects; each target group was identified as a beneficiary in at least 50% of projects (one project could serve multiple beneficiary groups). However, the Program’s reach varied among beneficiary groups. Across LFIF-1, -2 and -4, 2SLGBTQI+ people, people who are homeless, newcomers to Canada, Indigenous People and visible minorities were the least likely beneficiary groups to be served by projects in LFIF-1, -2 and -4 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total percent of projects by beneficiary group served, 2019-2022 (LFIF 1, 2 and 4)

[Description of the image above]

Figure 1 presents a horizontal bar graph showing the percent of each beneficiary group served by completed Local Food Infrastructure Fund projects during 2019 to 2022 and from intake periods 1, 2 and 4. The results were as follows:

- 59% of projects served 2SLGBTQI+ people

- 63% served the Homeless;

- 65% served Newcomers to Canada;

- 67% served Indigenous People;

- 68% served Visible Minorities;

- 77% served Persons with Disabilities;

- 79% served Groups with Social/Employment Barriers;

- 81% served Youth;

- 88% served Low-Income Seniors; and

- 94% served Low-Income Households.

| Demographic groups | Total percent served |

|---|---|

| 2SLGBTQI+ | 59 |

| Homeless | 63 |

| Newcomers to Canada | 65 |

| Indigenous | 67 |

| Visible minorities | 68 |

| Persons with disabilities | 77 |

| Groups with social/employment barriers | 79 |

| Youth | 81 |

| Low-income seniors | 88 |

| Low-income households | 94 |

Source: Programs Branch (final reports for completed projects submitted by recipients).

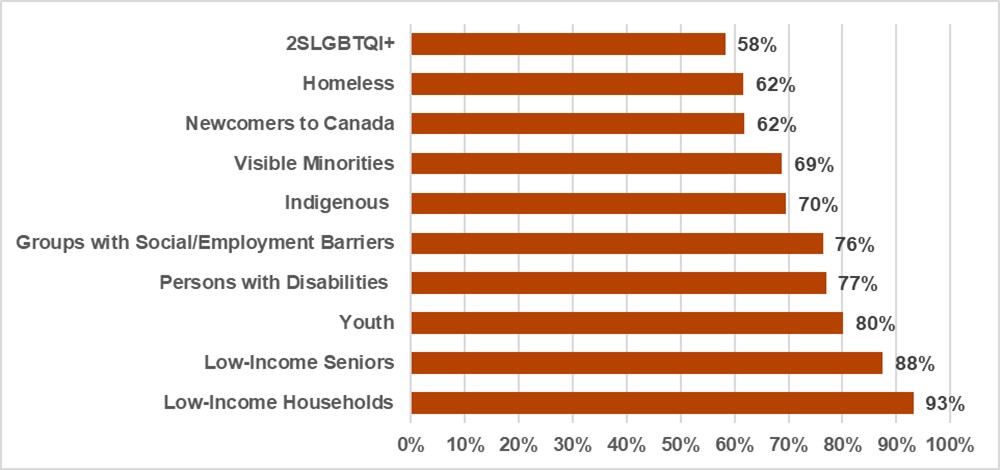

To assess accessibility and the Program’s reach, the evaluation also examined the total amount of funding invested in projects that benefited each of the LFIF’s target groups in LFIF 1, 2 and 4 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Total percent of LFIF funding by beneficiary group, 2019-2022 (LFIF 1, 2 and 4)

[Description of the image above]

Figure 2 presents a horizontal bar graph showing the percent of total program funding of each beneficiary group based on data of completed Local Food Infrastructure Fund projects during 2019 to 2022 and from intake periods 1, 2 and 4. The results were as follows:

- 58% of total program funding went to projects serving 2SLGBTQI+ people

- 62% of funding went to projects serving the Homeless

- 62% of funding went to projects serving Newcomers to Canada

- 69% of funding went to projects serving Visible Minorities

- 70% of funding went to projects serving Indigenous People

- 76% of funding went to projects serving Groups with Social/Employment Barriers

- 77% of funding went to projects serving Persons with Disabilities

- 80% of funding went to projects serving Youth

- 88% of funding went to projects serving Low-Income Seniors

- 93% of funding went to projects serving Low-Income Households

| Demographic groups | Total percent served |

|---|---|

| 2SLGBTQI+ | 58 |

| Homeless | 62 |

| Newcomers to Canada | 62 |

| Indigenous | 69 |

| Visible minorities | 70 |

| Persons with disabilities | 76 |

| Groups with social/employment barriers | 77 |

| Youth | 80 |

| Low-income seniors | 88 |

| Low-income households | 93 |

Source: Programs Branch (final reports for completed projects submitted by recipients)

The results demonstrate that the Program provided benefits to a diverse range of target groups, including populations with high levels of food insecurity. For example, a substantial amount of LFIF funding was invested in projects that benefited people from a low-income household. At the same time, other LFIF beneficiaries, such as 2SLGBTQI+ people, people who are experiencing homelessness, newcomers to Canada and visible minorities, were among the beneficiaries who received the least amount of total LFIF funding.

In summary, to increase accessibility and the Program’s reach, targeted communication with the LFIF’s priority populations should be integrated into initial program design through to program marketing, promotion and support for application processes; lessons can be drawn from the outreach and workshops that were completed with Indigenous organizations. Interviewees provided recommendations for how to potentially increase awareness. Notably, many recipients recommended that “traditional” advertising methods, such as radio, television and newspaper, may be more effective than social media, particularly for smaller, rural NGOs that do not use social media platforms. Additionally, AAFC officials recommended utilizing secondary data to identify food insecure communities, and targeting program advertisements in these areas.

6.0 Performance

This section provides an overview of the performance of the Program, including its progress toward expected outcomes and overall efficiency. The evaluation used case studies (including administrative and secondary data), service standards, peer-reviewed literature and key informant interviews to assess the Program’s performance.

6.1 Effectiveness

The Program made progress toward achieving its immediate and intermediate outcomes while little evidence suggested progress toward its ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity. Suitable indicators are used to assess effectiveness from the perspective of recipients; however, a lack of external validation and indicators regarding nutrition and GBA Plus limits assessments of program effectiveness.

Data measurement limitations

According to the literature, using a mix of subjective and objective data to assess performance is important, particularly for community food security programming. Subjective measurements, such as qualitative self-assessments of food security, often complement quantitative and objective observations of the food system and contribute to a more holistic understanding of food environments. Furthermore, as noted by Women and Gender Equality Canada, GBA Plus should be conducted routinely through key stages of the development of new and existing initiatives, from planning through to evaluation. This type of analysis involves examining how intersecting identity factors impact the effectiveness of policy and program initiatives and encourages datasets be disaggregated to accurately reveal inequalities and disproportionate outcomes between different population groups that aggregated data cannot.

The evaluation found that suitable indicators are in place for the Program to understand changes in the availability of and access to food, from the perspective of recipients. Various questions in the final reports enable recipients to assess a project’s effect on their organization’s capacity to produce or distribute food as well as changes in the availability of and access to food in the community. GBA Plus is supported by the Program systematically collecting information about the at-risk groups that are reported to be served by projects.

However, the evaluation also found that there is a lack of documentation to verify self-reported assessments; relying solely on self-reported data to assess performance risks reducing the reliability of performance results (in part because recipients tend to assess funding they receive positively). Furthermore, while increasing the availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food are key elements of the Program’s outcomes, data to understand the nutritional value of food associated with projects is not systematically collected. In final performance reports, funding recipients are asked to indicate changes in the volume and value (in dollars) of food but not the nutritional value of the food served.

Regarding GBA Plus, the evaluation found that data to assess the LFIF’s differentiated impacts on specific target or at-risk groups had significant limitations. Data for GBA Plus is collected primarily from organizations who are asked to report on the at-risk groups that are served through a project. Since many of the identity characteristics of LFIF’s beneficiaries groups cannot be determined based on appearance or observation (for example, sexual orientation, age or ability), it is unlikely that organizations can accurately report the demographic profile of their clients. In addition, aside from Indigenous organizations, the Program does not have a way to efficiently assess the extent to which other types of organizations are accessing and receiving funds from the Program (for example, organizations serving 2SLGBTQI+ people, newcomers or people who are homeless). Finally, while one ultimate beneficiary survey produced a food security profile of some LFIF ultimate beneficiaries, respondents were not asked questions about the Program’s direct (or indirect) impact on their food security status. The survey’s results are therefore limited for understanding the Program’s differential effects on each of the LFIF’s beneficiary groups and intersectional analysesEndnote 2.

From the peer-reviewed literature and interviews with subject matter experts, the evaluation identified several opportunities to improve the Program’s evidence base for the purposes of applying a GBA Plus lens and assessing progress toward achieving intended outcomes. In summary, a key challenge is ensuring that an adequate amount of information and evidence is collected from recipients while also monitoring for potential reporting burden. For example:

- The reliability of recipients’ self-reported assessments could be improved by requiring documentation from recipients to verify results.

- Additional mechanisms to disaggregate data that is collected directly from ultimate beneficiaries may improve GBA Plus.

- Systematic collection and verification of data on the nutritional value of food produced or distributed through projects would assist with more accurately understanding the Program’s effect on increasing access to and availability of healthy and nutritious food.

- External indicators, such as longitudinal metrics associated with changes in the food system, could be examined for their potential to improve the assessments of effectiveness.

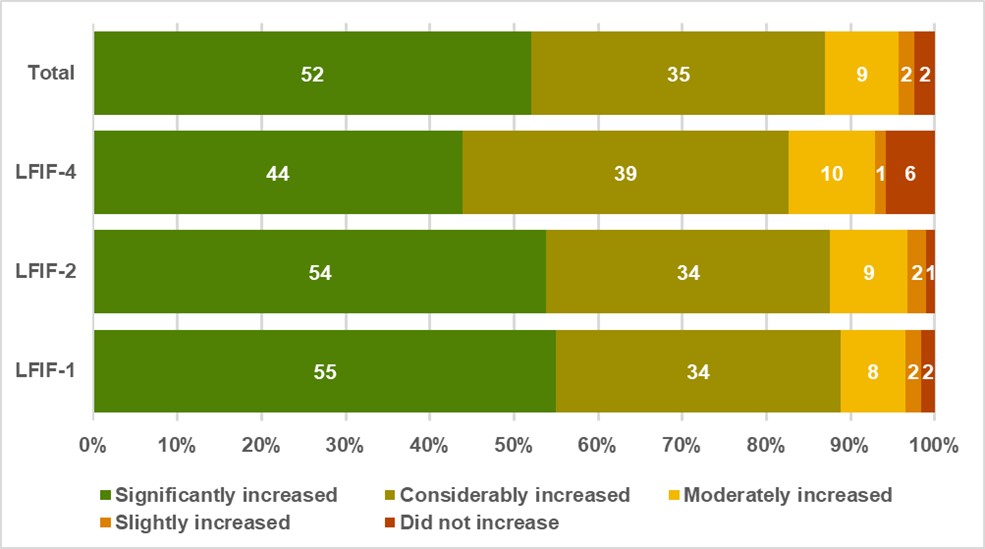

Outcome: Capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food

The Program’s immediate outcome is to increase organizations’ capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food in communities. Evaluation evidence shows that the Program has made progress toward achieving this outcome. In final project reports for LFIF-1, -2 and -4, the majority of funding recipients (87%) indicated that projects have been effective at increasing capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Increases in organizational capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food

[Description of the image above]

Figure 3 presents a 100% stacked bar graph showing the final project report results when funding recipients were asked to indicate on a scale the degree to which their organization’s capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food increased (1 being not at all to 5 being significantly increased). There are 4 stacked bars in the graph, including results for intake period 1, 2 and 4. The final bar is labelled as “Total” and this represents the sum of results from all of the intake periods evaluated. The results for the “Total” bar graph are as follows:

- 52% of funding recipients indicated that their organization’s capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food significantly increased

- 35% indicated that it considerably increased

- 9% indicated that it moderately increased

- 2% indicated that it slightly increased

- 2% indicated that it did not increase at all

| Percent of LFIF-1 Recipients | Percent of LFIF-2 recipients | Percent of LFIF-4 recipients | Percent of total recipients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly Increased | 55 | 54 | 44 | 52 |

| Considerably increased | 34 | 34 | 39 | 35 |

| Moderately increased | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| Slightly increased | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Did not increase | 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

Note: The figure is based on a sum of results contained in LFIF-1, LFIF-2 (grants), LFIF-2 (contributions) and LFIF-4 (grants) project final reports. Recipients were asked to indicate on a scale the degree to which their organization’s capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food increased (1=not at all to 5=significantly)

There were similar findings from interviews with recipients and AAFC officials; most of the funded recipients (81%) and the majority of AAFC officials (67%) indicated that projects have been effective at increasing organizational capacity. When asked if their organizations’ capacity had increased as a result of LFIF funding, the most notable change identified by recipients included expansion of space to grow, store, and distribute a larger amount of food to people in the community (and in a more consistent and timely basis).

In addition, food system partnerships created by organizations who received LFIF funding appears to have further contributed to increasing capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food. One of the case studies showed how projects that reported significant increases in organizational capacity attributed success, in part, to partnerships with other organizations. Furthermore, an analysis of qualitative responses provided by recipients in performance reports for LFIF-2 Grant projects found that almost half (44%) of these recipients indicated that an additional outcome achieved by project investments was increased or enhanced partnerships. This is consistent with the literature which suggests that collaboration acts as an enabler for community food security, and that projects with community involvement increase the effectiveness of community food security interventions.

For example, LFIF projects:

- helped build volunteerism within organizations and communities

- built relationships with other actors in the food system, including local businesses, schools and community organizations

- increased community engagement in the food system

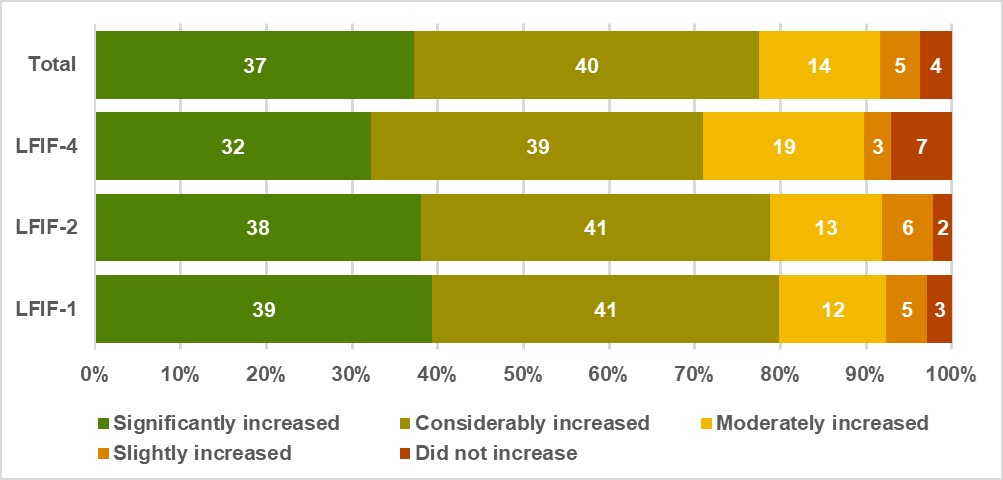

Outcome: Availability and access to healthy and nutritious food

Supporting the availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food is the LFIF’s intermediate outcome and a primary objective of community food security interventions. In project final reports for LFIF-1, -2 and -4, most recipients (77%) agreed that their project had considerably or significantly increased the availability of healthy and nutritious food in the community (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Increases in the availability of healthy and nutritious food in the community

[Description of the image above]

Figure 4 presents a 100% stacked bar graph showing the final project report results when funding recipients were asked to indicate on a scale the degree to which their project increased the availability of healthy and nutritious food in their community (1 being not at all to 5 being significantly increased). There are four stacked bars in the graph, including results for intake period 1, 2 and 4. The final bar is labelled as “Total” and this represents the sum of results from all of the intake periods evaluated. The results for the “Total” bar graph are as follows:

- 37% of funding recipients indicated that their projects significantly increased the availability of healthy and nutritious food in their community

- 40% indicated that it considerably increased healthy and nutritious food availability

- 14% indicated that it moderately increased healthy and nutritious food availability

- 5% indicated that it slightly increased healthy and nutritious food availability

- 4% indicated that it did not increase healthy and nutritious food availability at all

| Percent of LFIF-1 Recipients | Percent of LFIF-2 recipients | Percent of LFIF-4 recipients | Percent of total recipients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly Increased | 39 | 38 | 32 | 37 |

| Considerably increased | 41 | 41 | 39 | 40 |

| Moderately increased | 12 | 13 | 19 | 14 |

| Slightly increased | 5 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Did not increase | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| Source: The figure is based on a sum of results contained in LFIF-1, LFIF-2 (grants), LFIF-2 (contributions) and LFIF-4 (grants) project final reports. | ||||

Note: The figure is based on a sum of results contained in LFIF-1, LFIF-2 (grants) LFIF-2 (contributions), and LFIF-4 (grants) project final reports. Recipients were asked to indicate on a scale to what degree has the project increased the availability of healthy and nutritious food in your community (1=not at all to 5=significantly)

Furthermore, on average, recipients reported a:

- 140% increase in volume of food provided

- 138% increase in number of meals provided

- 103% increase in number of clients served

Considered as a whole, these statistics suggest that, on average, funding recipients were able to use LFIF-enabled infrastructure to increase the availability of food provided to clients, a result which is further supported by interviews with funding recipients and AAFC officials.

Outcome: Reduced household food insecurity

In final project reports, recipients were asked “to what degree has the project contributed to reducing household food insecurity in your community.” While the majority of recipients (65%) stated that projects reduced household food insecurity, the evaluation found no evidence of a direct or causal relationship between the Program and this result. There were no additional lines of evidence that indicated the LFIF made progress toward reducing household food insecurity. As mentioned, according to literature; interviews with experts, recipients, and AAFC officials; as well as empirical studies of food security programs, it is likely that there were other variables outside of the Program that contributed to recipients’ perceiving that there were reductions in household food insecurity (for example, responses indicating a reduction in household food insecurity may have been affected by bias toward assessing the Program favourably). Furthermore, since recipients are asked to report on the food security status of beneficiaries’ households, not their own, the accuracy of the result is further reduced.

6.2 Efficiency

Overall, the Program is administered efficiently; however, there is an opportunity to improve data and validation procedures for cost-efficiency assessments.

Efficiency of administration

The efficiency of administration is, in part, assessed using an “efficiency ratio.” This ratio is calculated by dividing the total administrative costs of a program by its total costs. The efficiency ratio for the Program has been decreasing since 2019 (2019-20: 30.8%; 2020-21: 12.4%; and 2021-22: 11.8%). This indicates that the Program has become more efficient in terms of distributing funds to recipients; the gap between internal operating expenses and external expenses has decreased.

During interviews, Program staff noted that several procedures are in place that support the efficiency of program delivery. For example, Programs Branch uses a centralized approach to administer the Program, with a standardized application form and guide. There are standard operating procedures that have been implemented to ensure adequate oversight and the cost-effectiveness of funding. This documentation includes guidance for Program officers when awarding and administering projects, such as procedures to process financial reports and thresholds for when projects require greater financial oversight.

Output effects

The evaluation’s assessment of efficiency included examining the extent to which resources were used such that a greater level of output was produced. The evaluation found some evidence that output effects associated with LFIF projects are likely greater than the initial investment.

The peer-reviewed literature on community food security suggests that programs such as the LFIF can have positive “downstream” effects, which increases the value of the initial investment. For example, community gardens and community kitchens can result in the transmission of food knowledge and skill development and longer-term relationships among members of the food system. The LFIF has encouraged relationship building through requirements for applicants to provide letters of support from other organizations and through prioritizing projects that benefit 2 or more areas of the food system.

One of the case studies showed how the construction of a greenhouse and the addition of an irrigation system to an existing garden in a remote community increased the availability of food. For example, the project was described as creating a “multiplier effect”: more people in the community were gardening and receiving food year-round. In addition to increasing food availability, the community has started to examine opportunities for new revenue streams to support the long-term sustainability of the project, in part through selling plants. The organization is also now starting to promote home gardening among community residents.

In the final reports for LFIF projects, recipients are asked to indicate changes in the value of food (in dollars) that their organization produced or distributed following the installation of LFIF-supported infrastructure. Analysis of responses to this question for LFIF 4 shows that there was an average food value increase of 235% over a 1-year period; in other words, organizations were able to maximize the LFIF investment, on average, by 235% (in terms of the value of food produced or distributed by the recipient organizations following the infrastructure purchase).

However, the evaluation identified issues with the quality and availability of data for efficiency assessments. There was a lack of supporting documentation to verify recipients’ reports of changes in food values and claims made regarding the multiplier effects of projects. In addition, in-depth analyses of cost-efficiency is further limited by the lack of a database containing an itemized list of items purchased with LFIF funds.

Service standards

Service standards for the Program includes:

- respond to general inquiries made by phone and email before the end of the next business day

- acknowledge receipt of application within a business day

- send an approval or a rejection notification letter within 100 business days of receiving a complete applicant package

- send a payment within 30 business days of receipt of a duly completed and documented claim.

Most of the reported service standards have met the established 80% target and, when asked during interviews, most applicants said that the Program’s activities were delivered efficiently. Overall, communication from the Program was found to be timely and general enquiries made to the LFIF email and phone number were answered promptly.

However, throughout quarters 1 and 4 of 2020-21 and quarters 1, 2 and 3 of 2021-22, some service standards were not achieved. Service standards that did not meet the 80% target during this period included responding to general inquiries to the LFIF email and sending payments within 30 days of a completed claim. The program area reported that these delays were the result of increased workload caused by the volume and complexity of applications in LFIF-2 and -4, as well as due to an overlap in payment disbursements for LFIF-1, -2 and -4.

Planned budget vs. actual spending

Finally, the evaluation found little variance between planned and actual spending (Table 3).

Table 3: Planned budget and actual spending

| Spending | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned spending | Actual spending | Difference | Planned spending | Actual spending | Difference | |

| Vote 1 (including Employee Benefit Plan) ($) | 1,357,377 | 1,564,850 | 207,473 | 1,357,376 | 2,699,839 | 1,342,463 |

| Vote 10 ($) | 10,981,800 | 11,056,921 | 75,121 | 10,981,800 | 20,268,851 | 9,287,051 |

| Total ($) | 12,339,177 | 12,621,771 | 282,594 | 12,339,176 | 22,968,690 | 10,629,514 |

|

Source: Corporate Management Branch, Estimates and External Reporting Section Notes: 2022-23 actual expenditures are not finalized. Vote 10 spending data does not include COVID Emergency Food Security Fund or COVID Surplus Food Rescue Program. |

||||||

The reasons for the discrepancies between the planned budget and actual spending included that:

- most of the recipients with contracted projects in 2019-20 were unable to complete their activities before March 31, 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, so projects were moved to the 2020-21 fiscal year

- there was an additional $10 million invested in the Program through Budget 2021

7.0 Conclusions and recommendations

The LFIF represents a new social policy program for AAFC, with new types of clients and at-risk beneficiaries. The LFIF is aligned with priorities in the Food Policy for Canada, AAFC Mandate Letters, TB documentation and federal budgets to support access to food, Indigenous food systems and food security. There was limited evidence demonstrating that the Program is aligned with its AAFC-associated core responsibility of domestic and international markets and no evidence suggested that the Program directly supports the sector’s competitiveness at home or abroad, exports, market access or international agricultural interests (each of which are fundamental components of the responsibility). However, while food security is not directly reflected in AAFC’s core responsibilities, it was found to be relevant to AAFC’s role in supporting various components of the food system. There is an opportunity for AAFC to review its role with food security in the context of its core responsibilities and existing programs.

The LFIF responds to a consistent and ongoing gap in funding for food security infrastructure in Canada. The Program’s broad range of eligible infrastructure types, beneficiary groups and its national scope fills gaps in programming in provincial and territorial jurisdictions where no such funding exists. However, there is some duplication with aspects of other federal, provincial and territorial programming.

The Program’s design is effective in terms of supporting community food security outcomes rather than the stated ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity. The LFIF does not address several factors that are critical for reducing household food insecurity, namely income support and supplementation, which are the responsibilities of other federal departments. However, it does enable activities at the community level which strengthens food systems, in particular through funding infrastructure which supports increasing access to food.

The Program has effective indicators in place to understand the LFIF’s effects from the perspective of recipients. For example, final project reports provide recipients the opportunity to report on demographic groups that were served and changes resulting from their respective projects. However, there is a lack of:

- documentation to validate recipients’ assessments in final reports

- food system metrics to assess the Program’s broader effect on the food environment

- data on the type of food produced and distributed through projects (to assess the Program’s outcome associated with healthy and nutritious food)

- data collected directly from beneficiaries that can be disaggregated to understand the Program’s differential impacts on beneficiary groups (GBA Plus)

Similarly, an itemized list of infrastructure items purchased and documentation from recipients to verify self-reported data were not identified, limiting the accuracy of cost-efficiency and other types of performance assessments. There is an opportunity for the Program to include indicators and datasets in the Performance Information Profile that provide sufficient and validated evidence to assess efficiency.

The Program made progress toward achieving its immediate and intermediate outcomes; however, there was little evidence to suggest that the ultimate outcome of reduced household food insecurity was achieved. Overall, the Program successfully reached its target groups and accessibility improved for some populations, such as Indigenous beneficiaries. Some beneficiary groups were less aware of the Program, leading to these groups receiving less benefits from the Program.

Finally, overall, the Program is administered efficiently. Despite increased demands placed on the Program area because of the Covid-19 pandemic, operational efficiency improved. Furthermore, recipients reported an increase in the value of food distributed after installing infrastructure, and investments in projects resulted in secondary benefits for individuals and communities.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy Branch, in consultation with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Management Branch, define AAFC’s role with supporting food security to inform potential changes to the Department’s core responsibilities.

Recommendation 2: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch adjust the Program’s ultimate outcome to better reflect its community food security design.

Recommendation 3: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch address opportunities to validate and improve program performance data to understand: achievement of community food security outcomes; differentiated impacts on target groups (GBA Plus); and cost-efficiency.

Recommendation 4: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Programs Branch examine past design changes and outreach activities to inform future efforts to increase access for the Program’s priority populations.

Management response and action plan

Management agrees with the evaluation recommendations and has developed an action plan to address them by March, 2024.

Annex A: Methodology

Local Food Infrastructure Fund (LFIF) activities from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2023 were evaluated between September 2022 and May 2023. At the time of this report, the LFIF is still being delivered. The evaluation was therefore considered formative, meaning that its purpose was to provide insights to inform future decision-making. The evaluation was based on the following methods.

Document and file review

A document and file review was conducted to obtain a better understanding of how the Program operates and to inform other lines of evidence.

| Document type | Number of documents |

|---|---|

| Program documents (briefing notes, memos, guidelines, etc.) | 32 |

| Program area analytical reports and decks | 39 |

| Speeches from the Throne | 2 |

| Federal budget speeches and economic updates | 3 |

| AAFC policies, mandates and commitments | 13 |

| Transcripts and reports from the House of Commons | 8 |

| Media articles | 15 |

| Total | 112 |

To analyze documents, evaluation questions and indicators were used as codes. Documents were analyzed deductively (in other words, documents were reviewed and information relevant to the evaluation’s questions and indicators—codes— were extracted). Synthesis involved a modified version of thematic analysisEndnote 3 by grouping, describing and interpreting codes to answer the evaluation questions.

Environmental scan

An environmental scan was completed to assist with assessing the extent to which the Program was filling a gap in the Canadian food security programming ecosystem. Internet searches were conducted from December 2022 to March 2023 to identify federal, provincial, territorial, municipal, not-for-profit and private sector food security programs in Canada. The evaluation team also met and communicated with program staff in other federal, provincial and territorial departments to collect information.

Literature review

The evaluation analyzed and synthesized academic and grey literature to support answering the evaluation’s questions. Literature was sourced from Google Scholar, the Canadian Agricultural Library and internet searches. Several search queries were executed between August and May 2023. Key words included: ‘food security’, ‘infrastructure’ and ‘Canada’; ‘food security’ and ‘theory’; ‘food security’ and [name of province/territory]; ‘food security’ and [demographic group identifier, such as ‘senior’, ‘youth’, ‘Indigenous’, etc.] and ‘Canada’; and ‘community food security’ and ‘indicators’ or ‘measurement’.

Exclusion criteria was established so that the literature could be reviewed within the project’s timeframe. Only articles that substantively focused on food security theory, food security infrastructure or the food security of a specific demographic group, province or territory was included. Literature was analyzed deductively by using the evaluation questions and indicators as codes. A modified version of thematic analysis was used to identify patterns and themes in the literature in relation to each code and to answer the evaluation’s questions. In total, 285 articles were determined to be relevant to the evaluation and were subsequently reviewed (219 peer-reviewed articles and 66 grey reports).

Analysis of administrative and secondary data

The evaluation analyzed and synthesized data provided by the program area including final project reports; a survey with ultimate beneficiaries, project descriptions and funding amounts; and data on outreach activities (for example, workshops with potential applicants). Secondary data included food security statistics published in peer-reviewed literature and datasets by Statistics Canada, Health Canada and external research centres.

Key informant interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted through video conferencing with internal and external stakeholders between December 2022 and January 2023. In total, 90 key informants were sent an invitation to participate in an interview and 41 were interviewed.

| Key informant type | Number of invitations | Number interviewed |

|---|---|---|

| AAFC officials | 9 | 8 |

| Applicants who received funding | 56 | 23 |

| Applicants who did not receive funding | 14 | 4 |

| Academic subject matter expertsNote 1 | 11 | 6 |

| Total | 90 | 41 |

|

||

Each interview was recorded with a de-identified summary transcript. Each transcript was reviewed individually. Structural coding and pattern codingEndnote 4 were used to analyze the transcripts (evaluation questions and indicators acted as codes to categorize responses to questions across all interviews). This resulted in summaries of interview results organized by evaluation indicator and question.

Case studies

The evaluation team completed 5 case studies to examine the extent to which the Program achieved its intended outcomes and the Program’s effect on marginalized groups (Indigenous People, people with from a low-income household and 2SLGBTQI+ people). The case studies used multiple lines of evidence: interviews with academics and researchers, AAFC officials, and applicants who received funding; analyses of secondary data and peer-reviewed literature on food insecurity; and analyses of program data regarding the Program’s effect. The results of the case studies were integrated throughout the report.

Triangulation

Methodological forms of triangulation were used to validate findingsEndnote 5. The project incorporated across-method, within-method, and sequential methodological approaches. For example, qualitative and quantitative methodologies were used separately, qualitative methodologies were used for more than one data source and one methodology informed the other. Triangulation also involved looking for findings from each line of evidence that converged and examining “outliers” in depth.

Limitations

| Limitation | Mitigation strategy | Impact on evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Response bias: Key informants who participated in the evaluation may have a vested interest in the continuation of programming | Interviews with participants from different groups generated a variety of perspectives. The evaluation included interviews with informants who had little to no vested interest in the Program, namely external academics with expertise in food security. Data was synthesized within and across stakeholder groups and triangulated with other lines of evidence to eliminate potential bias | Medium |

| Self-reporting bias: Recipients and ultimate beneficiaries who self-reported changes in food security may have misreported | Results were triangulated with studies of similar programs, interviews with academics, AAFC officials and recipients. Interviewees were asked probing questions specifically to assist with verifying self-reported results. The final report for the evaluation clearly described the limitations associated with self-reporting so that results can be interpreted appropriately. | High |