Combined Evaluation Report

The evaluation was approved by the Deputy Minister in March 2017.

Agriculture and Agri-food Canada

List of acronyms

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AMPA

- Agricultural Marketing Programs Act

- ANS

- Allowable Net Sales

- APP

- Advanced Payments Program

- ASRA

- Assurance Stabilisation des Revenues Agricoles

- BRM

- Business Risk Management

- CAIS

- Canadian Agricultural Income Stabilization

- CALA

- Canadian Agricultural Loans Act

- CANSIM

- Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System

- FIPA

- Farm Income Protection Act

- FPT

- Federal/Provincial/Territorial

- FTE

- Full Time Equivalents

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GF

- Growing Forward

- GF2

- Growing Forward 2

- NCI

- Net Cash Income

- NOI

- Net Operating Income

- NPAC

- National Program Advisory Committee

- NPF

- Next Policy Framework

- OAE

- Office of Audit and Evaluation

- OECD

- Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development

- PMS

- Performance Measurement Strategy

- PT

- Provincial/Territorial

- RAD

- Research and Analysis Directorate

- RML

- Reference Margin Limit

- RMP

- Risk Management Program

- SDRM

- Self-Directed Risk Management

- TAP

- Targeted Advanced Payment

- WLPIP

- Western Livestock Price Insurance Program

Executive summary

Purpose of the evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation was to examine the relevance and performance of AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance and the Wildlife Compensation Program. These programs are offered under the Business Risk Management (BRM) suite of programs as part of Growing Forward 2 (GF2), AAFC’s five-year (2013/14-2017/18) Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) Multilateral Framework Agreement for Canada's agricultural and agri-food sector.

The evaluation was conducted by the Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE) in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016). The results are intended to inform planning for the next phase of policy and program development under Next Policy Framework (NPF) beginning 2018/19, the next multilateral framework agreement for agriculture.

Background

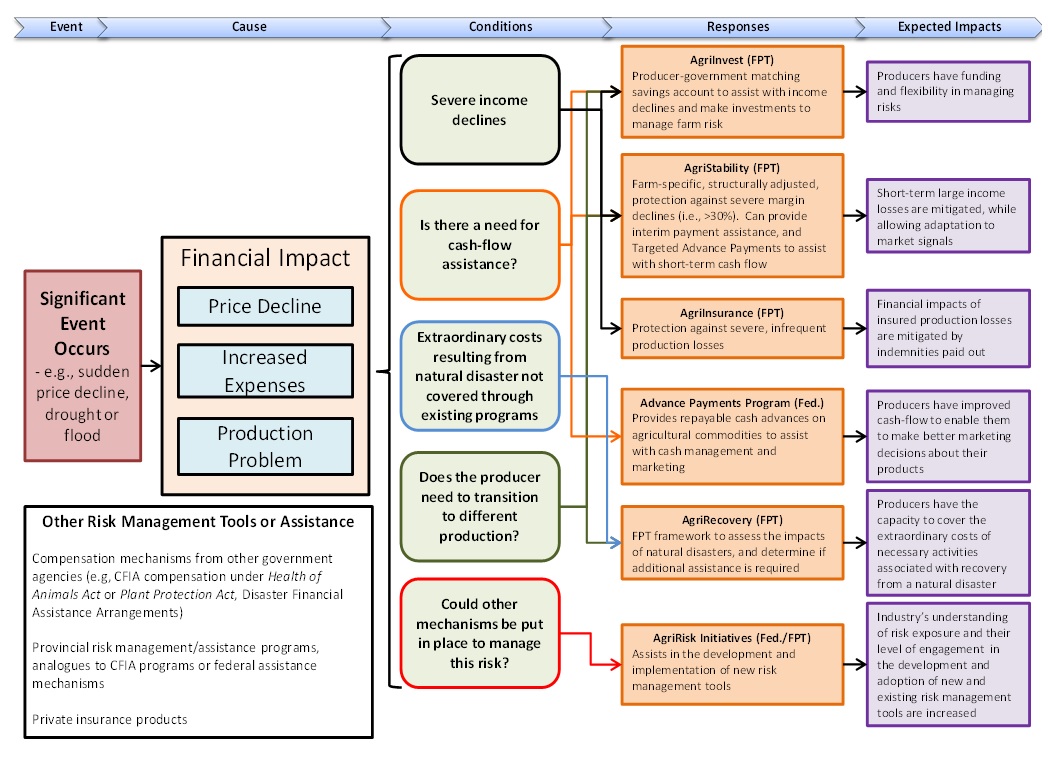

The BRM suite of programs is designed to support GF2 objectives by helping farmers manage risk due to severe market volatility and disaster situations. Within the suite are four core BRM programs: AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance and AgriRecovery. Other BRM programs outside the core suite include the Wildlife Compensation Program, AgriRisk Initiatives Program, loan guarantees under the Canadian Agricultural Loans Act (CALA), the Advance Payments Program (APP) delivered under the authority of the Agricultural Marketing Programs Act (AMPA), and the supply-management of a number of commodities.Footnote 1

AgriStability is a margin-based program that covers large income declines in a producer’s farm income relative to previous years. AgriInvest is a self-managed savings account into which a producer deposits funds and receives matching government contributions. AgriInsurance is a cost-shared production insurance program designed to reduce the economic effects of production losses caused by severe but uncontrollable natural hazards such as drought, flood, wind, frost, hail or snow, or losses resulting from uncontrollable diseases and insect infestations.

The Wildlife Compensation Program is a separate program from AgriInsurance but is also legislated under the Farm Income Protection Act (FIPA).Footnote 2 The Wildlife Compensation Program compensates producers for losses caused by wildlife either because producers are restricted from taking direct action against wildlife as a result of federal government regulation, or because there are no effective mitigation and prevention measures available to eliminate the losses. Producers are not required to participate in AgriInsurance to be eligible for the Wildlife Compensation Program and do not have to pay premiums or administration fees. Both crops and livestock are eligible for compensation under the Program.

The four programs (AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance and the Wildlife Compensation Program) are delivered through a mix of federal and provincial government administrations. Government contributions and costs to administer the programs are cost-shared by the federal government and provinces on a 60:40 basis. As the four programs are demand-driven, program expenditures fluctuate from year to year and payments to producers are based on program agreements. AgriStability payments fluctuate in accordance with program participation and industry conditions, increasing during sector downturns; AgriInvest payments are directly related to participation and allowable farm sales and purchases; AgriInsurance costs fluctuate based on commodity values and the number of acres insured; and Wildlife Compensation Program payments vary based on the number and value of claims. For the period from 2013/14 to 2017/18, the AgriStability budget is $1.43 billion, the AgriInvest budget is $0.81 billion, and the AgriInsurance budget is $3.23 billion, including the costs of the Wildlife Compensation Program.Footnote 3

Methodology

The evaluation was national in scope and covered the period from 2013/14 to 2016/17. It focused on understanding the effects of the changes made to the programs for GF2, both in terms of the programs meeting their objectives and also their administrative efficiency and economy.

The evaluation employed a summative, non-experimental design and gathered quantitative and qualitative data from the following lines of evidence:

- Document and literature review;

- BRM survey of a representative sample of 2,081 agricultural producers throughout Canada and from each commodity group;

- Interviews with 56 key informants including AAFC staff, provincial government representatives, agricultural industry associations and other stakeholders;

- Secondary data analysis which included analysis of various program databases maintained by AAFC; and

- Case studies of the following five sectors: hog, cattle, grains and oilseeds, supply managed commodities, and fruits and nuts.

Key findings and conclusions

The key findings and conclusions resulting from the evaluation are as follows:

Relevance

The Canadian agriculture sector has experienced positive growth on average over the past decade. Recent strong market conditions and high commodity prices led to significant growth in market revenues and profitability, particularly since 2013. Specifically:

- Total agricultural market receipts in Canada increased by over $26 billion between 2004 and 2015, growing from $31.5 billion to $57.6 billion;

- The overall profitability of Canadian farm operations (measured as total net operating income) more than doubled from $5.8 billion in 2004 to $15.2 billion in 2015 and the average net operating income per farmer more than doubled from $28,784 to $78,795; and

- The overall operating profit ratio (measured as net operating income as a percentage of operating revenues) also grew from 14 to 18 percent for an average farm-level.

While the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector has performed very well in recent years, there is a continued need for the BRM programming as many of the risks that can threaten the viability of a farm operation or commodity group are ongoing or cyclical and beyond producers’ control. These risks include:

- Production risks (for example, weather, disease, and pests);

- Market and price risks (for example, changes in market prices due to supply and demand fluctuations, international competition, exchange rates, tariff barriers, and input price volatility);

- Business risks (for example, access to credit, inadequate cash flow, fluctuating interest and exchange rates); and

- Policy risks (for example, trade agreements, environmental and food safety regulations, and border closures).

Private sector and producer-led tools and support mechanisms are insufficient in managing these risks. No private insurers or other institutions are currently involved in the delivery of multi-peril production insurance in Canada. Only a few private insurance products for livestock/animal diseases have been developed due to a lack of significant demand for coverage on the part of producers and an overall lack of industry capacity for developing these tools. To address this, the AgriRisk Initiatives Program supports the research and development, as well as the capacity building, of private risk management products and services for the sector.

The appropriate role of the BRM programming is to protect producers against market volatility and disasters and to encourage producers and the private sector to develop tools and strategies to manage normal business risk. This is in line with best practices identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and trends in government agricultural support in the United States, Australia and the European Union.

AgriInsurance, AgriStability and AgriInvest are aligned with federal roles and responsibilities legislated in FIPA. The Wildlife Compensation Program is somewhat aligned with federal responsibilities as there is a weak policy rationale for providing compensation for damages caused by non-federally protected species. AgriInvest and the Wildlife Compensation Program are less aligned with GF2 priorities and BRM principles due to their design as entitlement programs that primarily cover or compensate for normal business risks. There is evidence that some AgriInsurance products also cover some normal business risk. A 2011 OECD review of the AgriInsurance program in Canada found that crop insurance policies with deductibles of 10 percent trigger indemnities when yields are reduced below 90 percent of historical averages once every three years for the median farmer in Canada. The OECD review states that, at this frequency, these policies can be considered to cover frequently occurring losses due to normal variations in production.

Performance (effectiveness)

The evaluation findings and conclusions with regard to the effectiveness of each of the four programs evaluated are as follows:

- AgriInsurance

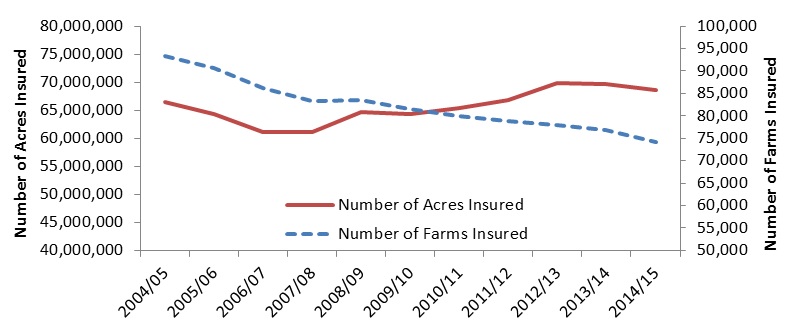

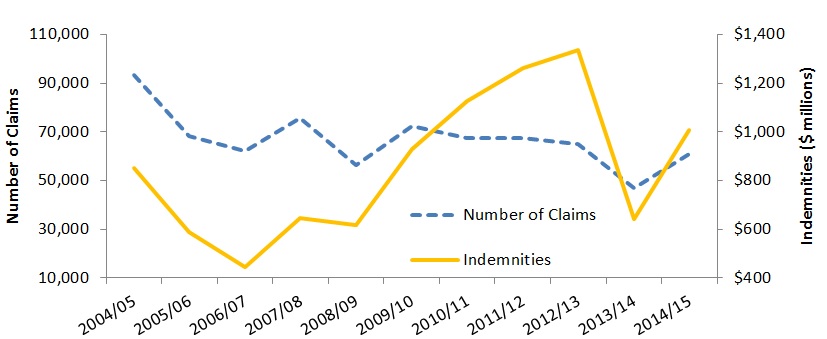

AgriInsurance is very effective in mitigating the financial impact of production losses for producers of eligible commodities. Participation has remained very high during Growing Forward (GF) and GF2, and producers are satisfied with the program overall. A large majority of agricultural commodities are eligible for insurance and program coverage has remained at approximately 75 percent from 2007/08 to 2014/15. The indemnities (compensation) paid have had a significant impact in mitigating the financial impact of production losses for producers of eligible commodities.

AgriInsurance is meeting most of its performance targets. The value of agricultural products eligible for AgriInsurance compared to the value of all agricultural products produced in Canada was 88 percent in 2013/14 and 87 percent in 2014/15 (target of 85%). The value of insured crop production compared to total production value was 16 percent for forage (target of 20%) and 76 percent for all other products (target of 75%). Low forage uptake has occurred because most cattle producers prefer to manage their feed risks on-farm rather than obtain insurance. Examples of on-farm management options of cattle producers include over-production and build-up of reserves; growth of annual crops (such as, greenfeed) to substitute for hay and pasture; purchase of feed from neighbors; and management of herd size relative to feed production. A federal/provincial/territorial task team has been assembled to identify options in forage insurance that could lead to increased uptake.

Other than forage insurance, AgriInsurance plans have not been developed and implemented for the cattle and hog sectors. Some progress has been made to implement a previous evaluation recommendation for AAFC to continue working with industry to develop livestock insurance plans where appropriate, and to explore the viability of alternatives outside of AgriInsurance. Using AgriRisk Initiatives, price insurance for cattle and hogs has been provided through a pilot of the Western Livestock Price Insurance Program (WLPIP). As WLPIP is not considered production insurance, it is therefore not under the AgriInsurance umbrella. However, WLPIP does appear to be a good example of an insurance program that allows producers to manage risks through premiums that are fully producer-paid and not subsidized by governments. Production insurance plans for hogs were investigated by an industry/government hog mortality task team; however, provinces are still considering the development of a product.

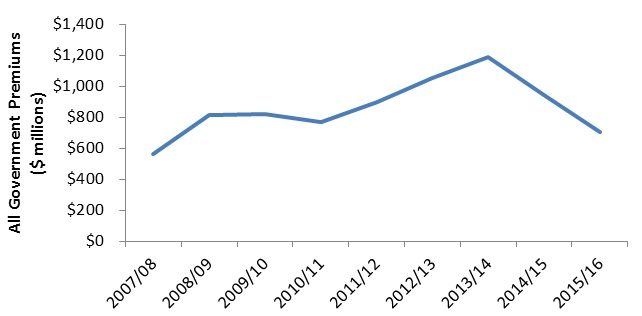

The value of agricultural production insured doubled from $7.27 billion in 2004/05 to $14.87 billion in 2014/15 as a result of increases in commodity prices, an ongoing transition to higher value crops and increases in insured acreage. Consequently, total AgriInsurance premiums paid by the federal and provincial governments almost doubled from $565.7 million in 2007/08 to $924.3 million in 2014/15.

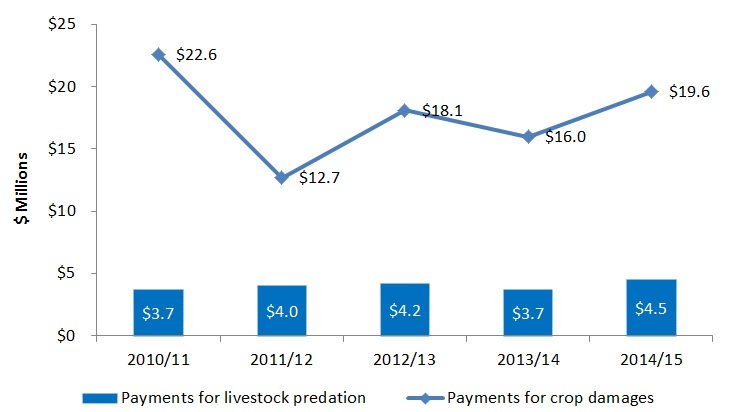

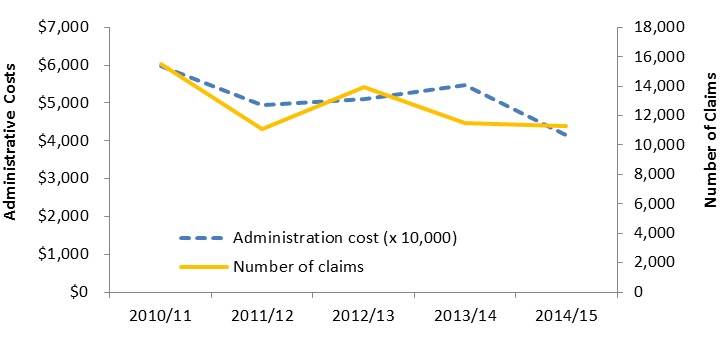

- Wildlife Compensation Program

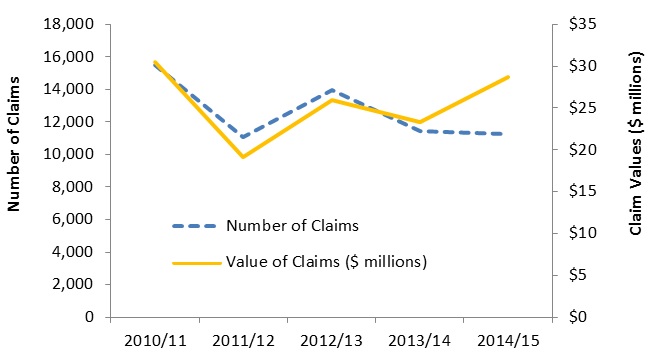

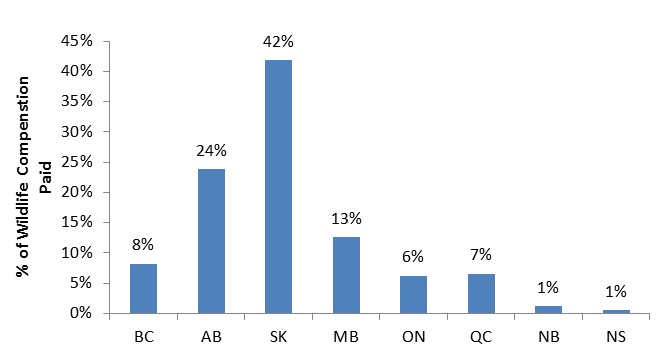

The Wildlife Compensation Program is effective in providing financial assistance for production losses due to wildlife damage to crops and predation of livestock. During the first two years of GF2 (2013/14 and 2014/15), an average of 11,362 claims have resulted in an average of $20 million in compensation paid to producers each year. Between 2010/11 and 2014/15, approximately 82 percent of the total compensation paid to producers was for damages to crops and 18 percent was for predation of livestock.

There is insufficient evidence as to whether producers who receive compensation make efforts to prevent a recurrence of losses. While each province that administers the Program has a requirement for producers to take mitigation measures and/or adopt best practices, the extent to which these are enforced is unknown. Requests to provincial governments for evidence regarding the types of prevention and mitigation efforts taken by producers to prevent recurring losses were not fulfilled during the evaluation.

In most provinces, the Wildlife Compensation Program has expanded beyond its original policy rationale to compensate for damages caused by federally protected waterfowl species and has no direct linkages to AgriInsurance. Québec is the only province that exclusively compensates producers for damages resulting from federally protected species, as originally intended, and damages from other wildlife species are only compensated as insurable perils under AgriInsurance. In all other participating provinces, the Program covers other non-federally protected wildlife species.

- AgriStability

Due to the nature of the program administration and timing of program payments, the most recent AgriStability data available for most performance indicators was for the 2013 program year, which limited the assessment to only one year of data regarding the changes made as a result of GF2. More years of program data are required to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the program and the impact of the changes made in GF2 to the AgriStability program.

A majority (64%) of BRM participants surveyed who received AgriStability payments between 2013 and 2015 reported that the payments are effective in helping them recover their income losses. Surveyed participants most frequently identified the primary benefits of the program as the ability to manage income losses and to even out income flow, the mitigation of impacts beyond their control, and the provision of a safety net.

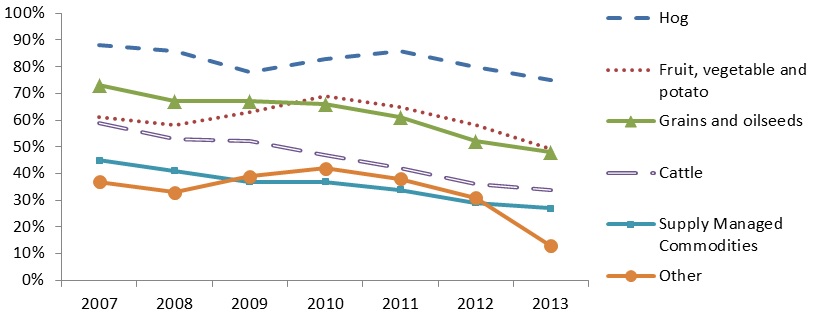

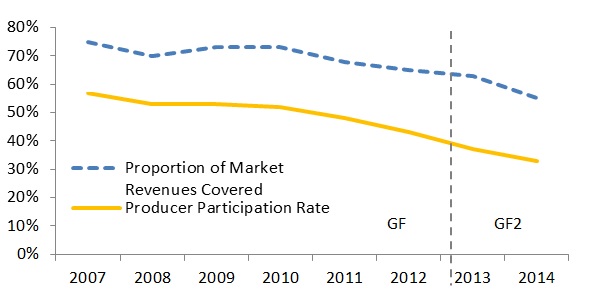

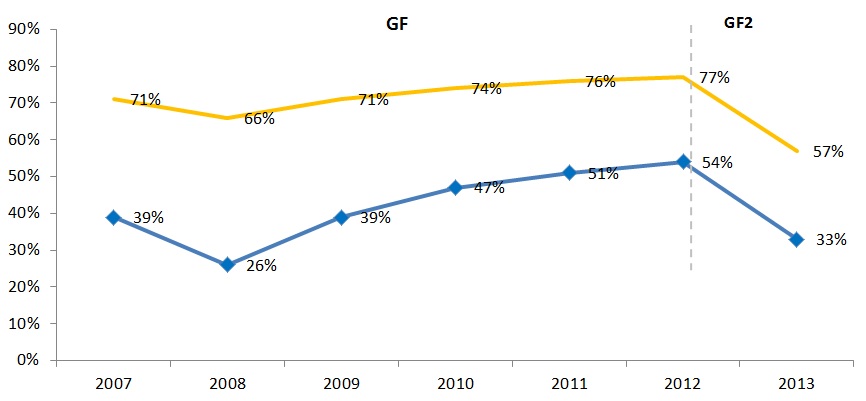

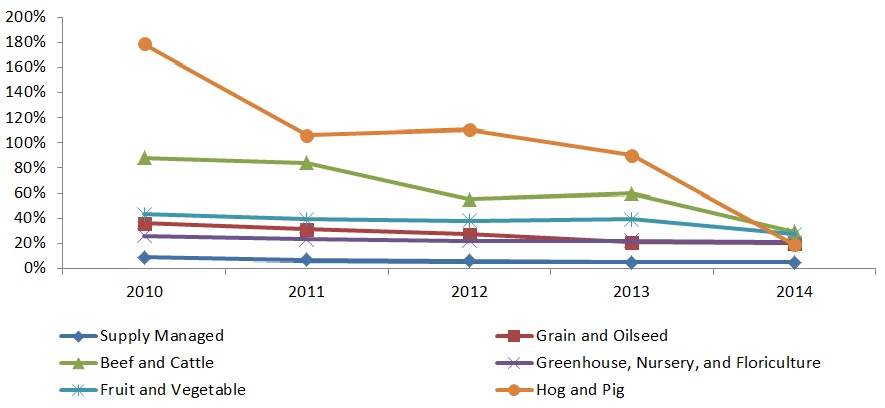

Even though AgriStability did not meet all its performance targets, related payments have been effective in mitigating the financial impacts of large short-term income losses as evidenced by the BRM survey result. The declining participation has limited the number of AgriStability beneficiaries while the number and value of payments have been further reduced by the GF2 changes. The number of producers participating in AgriStability has consistently declined over the past seven years, and has exceeded the decline in the number of farms in the industry. Under GF, the participation rate declined from 57 percent of producers in the 2007 program year to 43 percent in 2012, missing the performance target of 55 percent of producers participating in AgriStability. Under GF2, the participation rate further declined to 37 percent in 2013 and 33 percent in 2014, significantly below than the target of 50 percent. While declining participation has been consistent across all commodity groups, cattle producers have seen the most significant decline from 59 percent in 2007 to 34 percent in 2013. As of 2013, AgriStability program participation rates were highest among hog (75%), fruit, vegetable and potato (49%) and grains and oilseeds (48%) producers and lowest among producers of supply managed commodities (27%) and cattle (34%). Key informants attribute the decline in participation to the program’s complexity in how it functions, lack of transparency and predictability, lack of timeliness, the strength of recent prices/market conditions and GF2 changes to reduce coverage.

The participation rate in AgriStability, when measured as the percentage of market revenues covered by AgriStability participants, has not declined as dramatically (such as, from 75% in 2007 to 63% in 2013 and 55% in 2014) as the proportion of producers participating in the program. This can be explained by the fact that a higher proportion of larger producers participate in AgriStability compared to the proportion of smaller producers that participate in the program. The decrease in participation rate and coverage of the AgriStability program exposes the industry to more risk of significant losses and increases the potential demand for ad-hoc support.

- AgriInvest

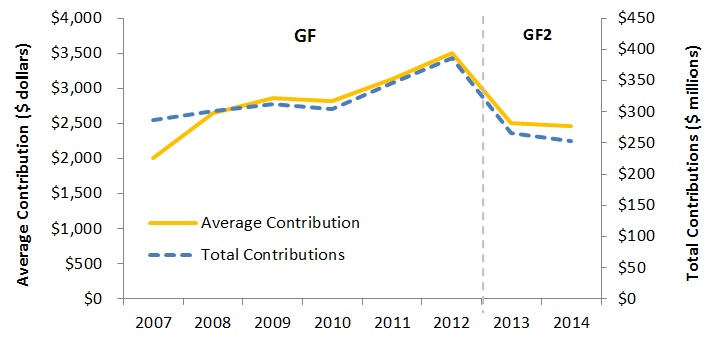

AgriInvest is somewhat effective in affording producers greater flexibility in managing financial risks and increasing producers’ capacity to deal with income losses. Participation and coverage of total market sales of AgriInvest participants are high and producers are setting aside funds. In 2013, 73 percent of producers participated in the program and 89 percent of all allowable market sales were covered. Account balances have grown to approximately $2 billion but are beginning to level out due to an increase in withdrawals and reduced contributions as a result of GF2 program changes, namely the reduced government contribution.

The program is considered by participants and key informants to be a somewhat effective tool for managing financial risk. Surveyed participants reported using the funds for cash flow (51%), farm related expenses (28%), to offset a decline in income (24%), to make on-farm investments (24%) or reduce debts (22%). Producers indicated that the main benefits of AgriInvest are the ability to manage income losses (40%), increase savings (36%), manage cash flow (35%), and make on-farm investments (21%).

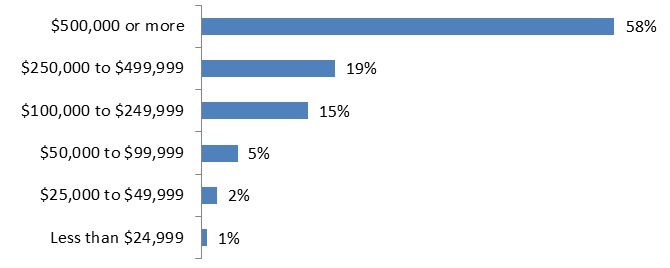

Many key informants, including producer association representatives, indicated that with a limit of $15,000, the AgriInvest matching contribution is not large enough to support a significant risk management investment or address an income loss as intended, especially given the increasing dominance of the agriculture sector by large farms and the fact that the majority of the $2 billion in AgriInvest account balances are held by large producers. Between 2008/09 and 2013/14, over one half (58%) of AgriInvest contributions were made by producers with sales revenues greater than $500,000 while producers with less than $100,000 in revenues accounted for only eight percent of total contributions.

Because the AgriInvest program guidelines do not stipulate that the funds withdrawn must be used to offset income losses, it is difficult to ensure that these funds are being used to manage financial risks and deal with income losses. The percentage of AgriStability participants that received an AgriStability payment and also made an AgriInvest withdrawal averaged 42 percent during GF and 44 percent during GF2, well below the performance target of 60 percent. Given strong market conditions and profitability in recent years, AgriInvest’s effectiveness in helping producers manage financial risks has not been tested.

Performance (efficiency and economy)

The evaluation findings and conclusions with regard to the economy and efficiency in which the four programs are delivered are as follows:

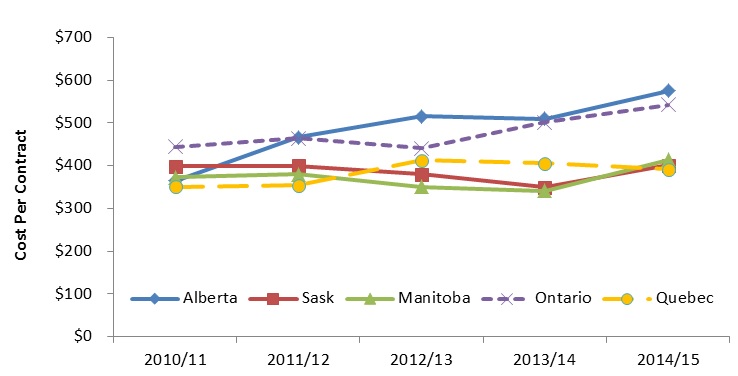

- AgriInsurance

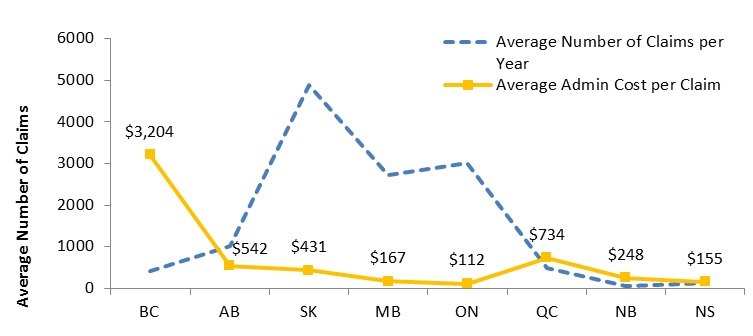

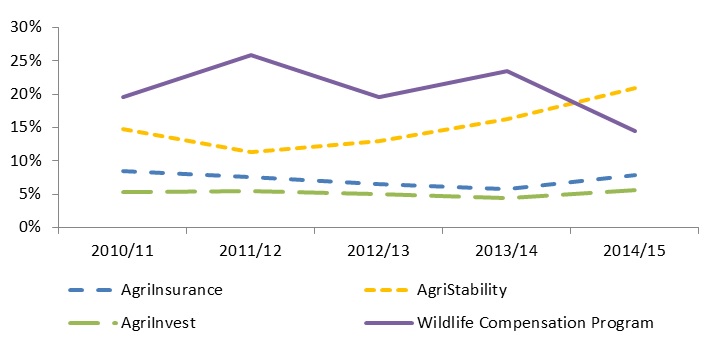

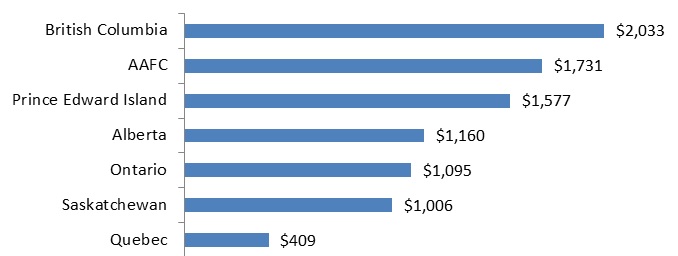

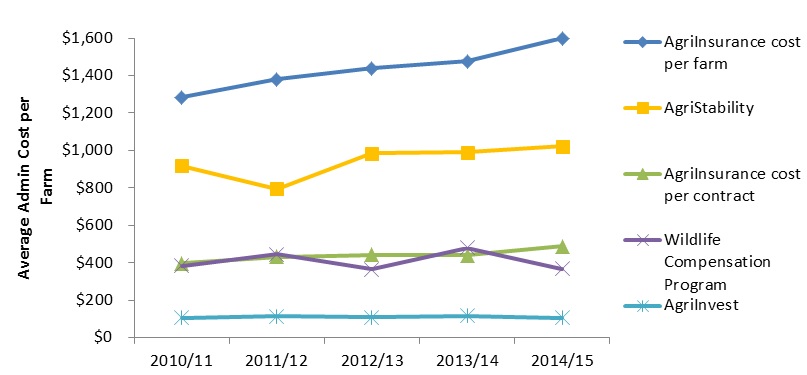

AgriInsurance is delivered efficiently and economically compared to other production insurance programs in other countries. However, increases in administrative costs combined with a decline in the number of insured contracts have resulted in a 23 percent increase in the administrative cost per contract, from $397 in 2010/11 to $487 in 2014/15. In recent years, AAFC has devoted efforts to control cost increases (for example, by examining the potential for sharing of IT development costs by provincial production insurance programs). - Wildlife Compensation Program

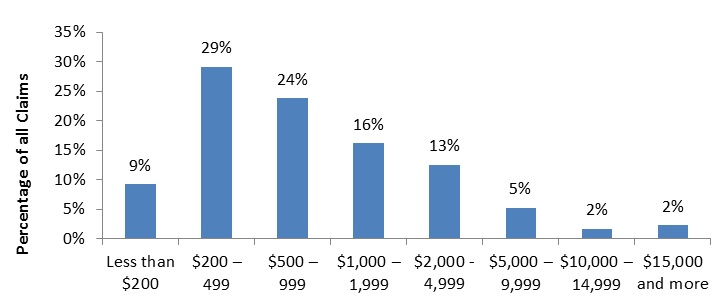

The administrative costs per claim of the Wildlife Compensation Program are high due to the cost of the on-farm inspection needed to comply with the federal requirement for evidence of loss. The administrative costs as a proportion of program funding are higher for the Wildlife Compensation Program than the other programs evaluated due to the preponderance of small claims. Approximately 38 percent (23,564) of the claims paid from 2010/11 to 2014/15 were for less than $500. For most of these claims, the administrative cost is equal to or greater than the claim amount, considering that the average administrative cost per claim is $405. - AgriStability

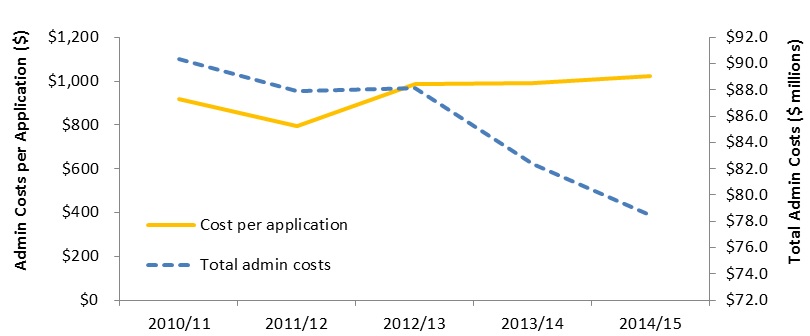

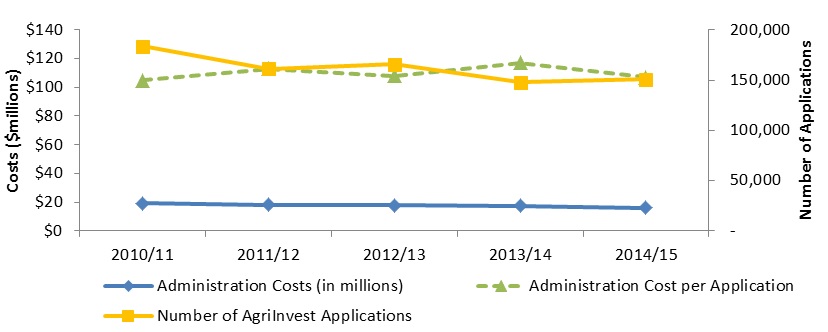

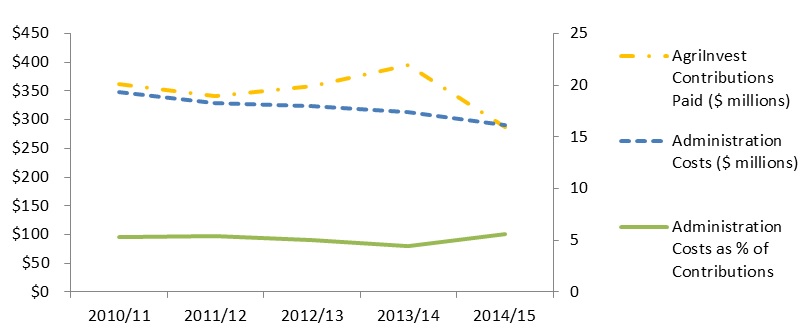

For the most part, AgriStability is delivered as efficiently and economically as possible, given the administrative complexity of the program. The 22 percent decline in the number of AgriStability applications that occurred between 2010/11 and 2014/15 fiscal years led to a 13 percent reduction in total administrative costs from $90.3 million to $78.4 million. However, due to the resulting losses of economies of scale, the administrative cost per application increased 11 percent from $918 in 2010/11 to $1,022 in 2014/15. Because program administrative processes have not yet been adjusted sufficiently to reflect the transition from an income support program to assisting producers in dealing with market volatility and disaster events beyond their control, the reduction in the number and value of payments as a result of declining participation and GF2 program changes have led to a 42 percent increase in administrative costs as a percentage of payments to producers. While there exist some opportunities to share best practices across jurisdictions, significant gains in efficiency would require making the program administratively less complex in line with its new focus. However, the scope of the evaluation did not include an assessment of any such program design options to streamline AgriStability. AgriInvest

AgriInvest is delivered efficiently as a result of its simple design and highly streamlined and automated delivery. While the program administration is efficient, AgriInvest’s cost-effectiveness is impeded by the high proportion of participants that make very small contributions, resulting in comparatively high administrative costs for limited program benefits for small producers.Contributions ranging from $75 to $1,000 accounted for about one half (47%) of the total number of contributions processed in 2014/15. As the average administrative cost to process an AgriInvest contribution was $107 in 2014/15, many of these deposits are too small to justify the administrative expenditure to process and pay the government contribution. The ratio of administrative costs to process an AgriInvest contribution compared to the average amount of an AgriInvest contribution is approximately 25 percent for the 44,328 (47%) contributions that are less than $1,000.

The current minimum contribution for AgriInvest is $75. As a comparison, a minimum contribution value of $1,000 has been used by a similar program in Australia (such as, Farm Management Deposit Scheme) to reduce administrative costs. While some administrative cost savings could be obtained by increasing the AgriInvest minimum contribution, thereby reducing the number of AgriInvest contributions required by AAFC each year, the administrative savings would not likely be proportional to the reduction in number of applications processed, due to the highly automated nature of application processing.

Recommendations

The key issues and recommendations resulting from the evaluation findings are as follows:

AgriInsurance

- Issue #1:

In response to OECD-identified best practices in government agricultural support and the sector’s increased capacity for managing normal business risk, GF2 objectives were revised to target government support to more severe and catastrophic losses and encourage producers to manage normal business risks. As identified in the 2011 OECD thematic review of Canadian risk management and AAFC’s internal review of AgriInsurance risk coverage, some AgriInsurance products are covering some normal business risk.- Recommendation #1:

AAFC should work with the provinces to examine options to modify products identified as covering normal business risk to transfer greater responsibility to producers and better align the coverage levels provided by AgriInsurance with current GF2 objectives and BRM principles.

- Recommendation #1:

- Issue #2:

As a result of recent increases in commodity prices, an ongoing transition to higher value crops and increases in insured acreage, the total AgriInsurance premiums paid by the federal and provincial governments almost doubled from $565.7 million in 2007/08 to $924 million in 2014/15. While AgriInsurance is for the most part delivered efficiently and economically, increases in administrative costs combined with a decline in the number of insured contracts, resulted in a 23 percent increase in the administrative cost per insurance contract over the last five years.- Recommendation #2:

While some efforts to control costs have been undertaken, AAFC should work with the provinces to identify additional cost-control mechanisms to prevent significant increases in AgriInsurance administrative costs as well as in government premiums should commodity prices and the total value of agricultural production insured continue to increase.

- Recommendation #2:

- Issue #3:

There are limitations with the current AgriInsurance performance indicators for efficiency. As an illustration, one indicator is program administrative expenses as a percentage of total premiums. Because premiums have increased considerably in recent years due to increased commodity prices, this performance indicator shows a decrease in administration costs as a percentage of premiums which does not reflect changes in AgriInsurance administrative costs.- Recommendation #3:

AAFC should work with the provinces to refine the performance measures used to assess the efficiency and economy of the administrative costs to deliver AgriInsurance.

- Recommendation #3:

Wildlife Compensation Program

- Issue #4:

The administrative costs per claim of the Wildlife Compensation Program are high due to the cost of the on-farm inspection needed to comply with the federal requirement for evidence of loss. Due to the preponderance of small claims, administration costs as a proportion of program funding are higher for the Wildlife Compensation Program than the other programs evaluated.- Recommendation #4:

AAFC should work with the provinces to reduce administrative costs by adopting a minimum claim amount (for example, $1,000) or charging an application processing fee. Additional opportunities to save on administrative costs should be investigated including reducing federal requirements for on-farm inspection and verification of loss, eliminating payments for recurrent losses, pooling of small claims until they reach the minimum amount, and promoting initiatives to enhance producer preventative efforts to reduce or eliminate the need for compensation.

- Recommendation #4:

- Issue #5:

The Wildlife Compensation Program has expanded beyond its original policy rationale to only compensate for federally protected waterfowl species and has no direct linkages to AgriInsurance outside of Québec. Québec is the only province that exclusively compensates producers for damages resulting from federally protected species, as originally intended, while damages from other wildlife species are compensated as insurable perils under AgriInsurance. In all other participating provinces, the Wildlife Compensation Program covers federally protected waterfowl species as well as a wide variety of non-federally protected wildlife species.- Recommendation #5:

AAFC should work with the provinces to continue to investigate the feasibility of including wildlife damages as an insurable peril under AgriInsurance and restricting eligible wildlife to those species protected under federal legislation to better align with government mandates and responsibilities.

- Recommendation #5:

AgriStability

- Issue #6:

AgriStability’s design, which includes the calculation of payments based on individual farm finances, requires a very extensive set of benchmarks and indicators that impedes the program’s administrative efficiency, timeliness and transparency. Due to the transition from an income support program to assisting producers in dealing with market volatility and disasters in GF2, the number and value of AgriStability payments to producers has decreased in 2013 and will likely continue at this level in subsequent years. However, the administrative costs to process the AgriStability applications have not been reduced proportionately because similar program delivery processes are still being employed. Consequently, administrative costs as a percentage to the payments to producers have increased from 15 percent in 2010/11 to 21 percent in 2014/15. While there appear to exist opportunities to reduce administrative costs by streamlining existing processes and sharing best practices across the provinces, significant gains in efficiency would require a major change in the design of the program or administrative approach to reduce administrative complexity and costs in line with its new focus under GF2.- Recommendation #6:

AAFC should work with the provinces to examine options to reduce AgriStability complexity and, in turn, decrease administrative costs. This will require a re-design of the program to reflect the transition from an income support program to providing producers assistance under severe situations. This could potentially decrease the frequency and amount of information that must be collected from producers as well as reduce program administrative costs.

- Recommendation #6:

- Issue #7:

The number of producers participating in AgriStability has consistently declined over the past seven years from 57 percent in the 2007 program year to 33 percent in 2014. However, the percentage of market revenues covered by AgriStability participants (another measure of participation rate) has not declined as dramatically (such as, from 75% in 2007 to 55% in 2014) as a result of high participation rates among large producers. The decrease in participation rate and coverage of the AgriStability program exposes the industry to more risk and increases the potential demand for ad hoc support. Producer participation is expected to remain low (as forecast by AAFC and provincial Ministries of Agriculture) if significant steps are not taken to make the program more predictable and less complex, expensive and cumbersome to apply.- Recommendation #7:

AAFC and the provinces should monitor the participation rate of producers in AgriStability to ensure that the program provides coverage to producers in need to avert the need for ad-hoc programming and payments. Analysis should be undertaken to determine what participation rate would assure a meaningful coverage for the industry, and strategies to facilitate a sufficient number of producers participating in the program should be developed.

- Recommendation #7:

AgriInvest

- Issue #8:

AgriInvest contributions are based on one percent of a producer’s allowable net sales rather than an income loss. Because AgriInvest is an entitlement program that primarily covers or compensates producers for normal business risks, it is not well aligned with GF2 objectives and demand-driven BRM programming that are based on need. In recent years, approximately $260 million in government contributions per year have been deposited in AgriInvest savings accounts despite account balances of about $2 billion in 2014/15 and reduced need as a result of strong market conditions, record profitability, low interest rates and positive farm financial conditions.- Recommendation #8:

AAFC should work with the provinces to clarify AgriInvest objectives and linkages within the context of the BRM suite of programs. The assessment should inform AAFC and the provinces regarding program design options to support flexibility in risk management while strengthening the program’s linkages to GF2 priorities and BRM principles. For example, a potential role of AgriInvest could be to offset a decline in coverage by AgriStability. An option to be explored is to clarify and exercise the cross compliance clause in the GF2 FPT Multilateral Framework Agreement in conjunction with the provinces to implement conditions for producer participation in AgriInvest.

- Recommendation #8:

- Issue #9:

Many AgriInvest producer deposits are too small to justify the $107 average administrative expenditure to process and pay the matching government contribution. In 2014/15, contributions ranging from $75 to $1,000 accounted for approximately one half (47%) of the total number of contributions processed while contributions less than $500 accounted for about 30 percent. The ratio of administrative costs to process an AgriInvest contribution compared to the average amount of an AgriInvest contribution was approximately 41 percent for contributions less than $500. Due to the high ratio of administrative costs to AgriInvest contribution for these smaller amounts, savings in administration costs could be obtained by increasing the minimum contribution amount of $75 and/or producers share in the program administration costs. As a comparison, a similar program in Australia uses a minimum contribution of $1,000. To address the concern that smaller producers would not be able to participate if the minimum contribution were increased, some options could be considered such as allowing a producer to pool revenues for several years until they are sufficient to allow participation in the AgriInvest program or to develop a tax credit program which can more efficiently address small contributions.- Recommendation #9:

AAFC should work with the provinces to increase the minimum contribution that will justify the administrative expenses to process the AgriInvest contribution and/or producers share in the program administration costs.

- Recommendation #9:

1.0 Introduction

The Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE) conducted an evaluation of AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance and Wildlife Compensation Programs. These programs are offered under the Business Risk Management (BRM) suite of programs as part of Growing Forward 2 (GF2), AAFC’s five-year (2013/14-2017/18) Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) Multilateral Framework Agreement for Canada's agricultural and agri-food sector. The evaluation fulfills a requirement and commitment under AAFC’s Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan and the Financial Administration Act. With the GF2 policy framework expiring at the end of 2017/18, the results are intended to inform planning for the next phase of policy and program development under the next multilateral framework agreement for agriculture, Next Policy Framework (NPF), after GF2 ends.

As the four programs have common BRM objectives and are designed with numerous linkages to provide a complementary suite of programming, the programs were evaluated together. Other BRM programs were subject to separate evaluations but are included in the BRM suite of programming:

- AgriRecovery was evaluated in 2015/16;

- The Advanced Payments Program was evaluated in 2015/16; and

- The Canadian Agricultural Loans Act Program was evaluated in 2013/14.

1.1 Evaluation scope

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016). As per the Directive on Results, the evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the following programs: AgriStability, AgriInvest, AgriInsurance and the Wildlife Compensation Program. Specifically, the evaluation examined the following: continued need for the programs; alignment with government priorities, departmental strategic outcomes, and federal roles and responsibilities; achievement of intended outcomes; and the extent to which the programs demonstrate efficiency and economy.

The evaluation was national in scope and covered the period from 2013/14 to 2015/16. Data collection started in January 2016 and concluded in July 2016. It focused on understanding the effects of the changes made to the programs for GF2, both in terms of the programs meeting their objectives and also their administrative efficiency and economy. Some other objectives of the evaluation were to determine what have been the short and long-term economic outcomes associated with these programs, and how they have contributed to the adaptability of the agricultural sector.

1.2 Evaluation approach

The evaluation was conducted by the AAFC Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE). It employed a summative, non-experimental design and incorporated both primary and secondary data. Multiple lines of evidence were used to address evaluation issues and questions that were developed in collaboration with program managers.

1.3 Methodology

The evaluation consisted of the following lines of evidence:

- A document and literature review was conducted to gather information relevant to the evaluation questions and issues of relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. The review examined foundational documents on policy rationale and the design and operation of the programs; program documents on performance and accomplishments; federal policies, branch and departmental documents and reports; and peer reviewed articles as well as other relevant literature. A complete list of documents and literature reviewed can be found in Annex B.

- A BRM survey of producers was conducted between February and March 2016 and included data on 2,081 producers across Canada which was obtained through a random sampling of Canadian producers. The survey was conducted jointly by OAE and the BRM Programs Directorate.

- An analysis of secondary data was undertaken which included the following: Farm Income Programs Directorate program administrative and financial data; program data from the PINSS AgriInsurance database, AgriInvest National Program Database and Québec database; AgriStability National Program Database and the Wildlife Compensation Program National Program Database; and Statistics Canada Farm Financial Survey Data. The data gathered through these analyses were used to examine issues related to the relevance and effectiveness of the BRM programs.

- Semi-structured interviews with 56 key informants were conducted between February and April, 2016 to gather perspectives on the programs from key stakeholder groups. Interviewees included 11 AAFC executives, managers and staff; 23 provincial government program representatives; and 22 representatives of agricultural commodity groups, the National Program Advisory Committee (NPAC) and farm financial advisors.

- Commodity group case studies were completed to analyze differences in need across various commodity groups, the responsiveness of the programs to these needs, and how the programs impact incomes and the management of risks. Case studies were undertaken of the following five commodity groups: cattle, hogs, grains and oilseeds, supply-managed commodities and fruits and nuts. The case studies involved a document review and an analysis of secondary data on program participation and the impact of government programming on each commodity group.

1.4 Methodological considerations

The considerations or limitations to note for this evaluation are as follows:

- It was difficult to conduct a detailed assessment of the combined impact and interrelationships of BRM programs at the producer level because of the lack of an integrated database of all BRM program participants. As a result, the evaluation relied on external data at a summary level to assess the combined impact of all federal and provincial government programs on the net income of program participants.

Due to the nature of the program administration and timing of program payments, the most recent AgriStability data available for most indicators was for the 2013 program year, which limited the assessment to only one year of data regarding the changes made as a result of GF2. One year of data is not sufficient to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the impact of the changes made in GF2 to the AgriStability program.

2.0 Profile of the programs

2.1 Background

Growing Forward 2 (GF2) is the current FPT agricultural policy framework from 2013/14 to 2017/18. Under GF2, governments agreed to work together to achieve three strategic outcomes:

- A competitive and innovative sector;

- A sector that contributes to society’s priorities; and

- A sector that is proactive in managing risk.Footnote 4

The BRM suite of programs is intended to support GF2 strategic outcomes by helping farmers manage risk due to severe market volatility and disaster situations. The objectives of GF2 reflect a shift towards encouraging producers to manage more normal business risks with government support being targeted more towards severe and catastrophic losses. A market-oriented focus on adaptability and competitiveness is a new addition to intended outcomes under this framework. The BRM program suite end outcomes have been updated to reflect the objectives of competitiveness and adaptability.

GF2 includes four core BRM programs:

- AgriStability is a margin-based program that covers declines of more than 30 percent in a producer’s program margin relative to their reference margin.

- AgriInvest is a self-managed savings account into which a producer deposits funds and receives matching government contributions. The funds can be used to cover small income declines or to make investments in risk management or to help improve market income.

- AgriInsurance is a cost-shared production insurance program designed to minimize the economic effects of production losses caused by uncontrollable natural hazards (for example, drought, flood, wind, frost, hail or snow) or losses resulting from uncontrollable diseases, insect infestations and wildlife.

- AgriRecovery is a disaster-relief framework that provides a coordinated process for FPT governments to respond rapidly when disasters strike, assisting with extraordinary costs not covered by the existing programs.Footnote 5

Other BRM programs outside the core suite include the Wildlife Compensation Program, AgriRisk Initiative Program, loan guarantees under the Canadian Agricultural Loans Act, the Advance Payments Program (APP) delivered under the authority of the Agricultural Marketing Programs Act and the supply-management of a number of commodities (for example, dairy, poultry and eggs).

AgriStability and AgriInvest were implemented in 2007 to replace the Canadian Agricultural Income Stabilization (CAIS) program, which operated from 2003/04 to 2006/07 under the predecessor to Growing Forward (GF), the Agricultural Policy Framework. AgriStability and AgriInvest are governed under the provisions of Section 4(1) of the Farm Income Protection Act (FIPA), which authorizes the Minister to establish programming with the provinces to stabilize net income.

Federal support for production insurance was first formalized by the Crop Insurance Act (1959). AgriInsurance was subsequently legislated under Section 4 of FIPA, which authorizes the Minister to enter into an agreement with one or more provinces for the establishment of a crop insurance program.

The Wildlife Compensation Program, a separate program from AgriInsurance, compensates producers for losses caused by wildlife either because producers are restricted from taking direct action against wildlife as a result of federal government regulation or because there are no effective mitigation and prevention measures available to eliminate the losses. Both crops and livestock are eligible for protection under the program. Because the predecessor Waterfowl Program was included in the provinces’ crop insurance agreements under FIPA in 1991, the Program is legislated under Section 4 of FIPA. Producers are not required to participate in AgriInsurance to be eligible for the Wildlife Compensation Program and are not required to pay premiums or administration fees.

Annex B provides more details on all four programs.

3.0 Evaluation findings

3.1 Relevance

The following section outlines the key findings and conclusions resulting from the evaluation related to the relevance of, and continued need for the four programs.

3.1.1 Continued need for the programs

While the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector has performed very well in recent years, there is a continued need for the BRM programs to help producers manage risks associated with severe market volatility and disaster situations. Many of the risks that can threaten the viability of a farm operation or commodity group are ongoing or cyclical and beyond producers’ control. On their own, private sector and producer-led tools and support mechanisms are not broad enough to manage these risks.

Current state of the agricultural sector

Over the past five years, the Canadian agriculture sector has enjoyed strong market conditions and high commodity prices, partly due to positive macroeconomic factors including the depreciation of the Canadian dollar vis-à-vis the United States dollar, which has significantly improved the competitiveness of Canadian agricultural commodities in international markets.Footnote 6 Total farm market receipts have increased by over 80 percent from $31.5 billion in 2004 to $57.6 billion in 2015. The most significant gains occurred in grains and oilseeds production, which experienced a 163 percent growth in revenues from $7.6 billion in 2004 to $20.1 billion in 2015 (Table 1). Likewise, pulse and special crop production has experienced double digit growth in five of the past 10 years.

| Year | Grains and Oilseeds | Cattle | Hog | Fruit, Vegetable and Potato | Supply Managed Commodities | Greenhouse Nursery and Floriculture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | $7.9 | $6.4 | $4.7 | $2.2 | $8.1 | $2.7 |

| 2005 | $7.3 | $8.2 | $4.6 | $2.2 | $8.6 | $2.9 |

| 2006 | $7.9 | $9.1 | $4.2 | $2.4 | $8.8 | $3.3 |

| 2007 | $10.9 | $9.0 | $4.1 | $2.6 | $9.4 | $3.3 |

| 2008 | $14.8 | $9.2 | $3.8 | $2.8 | $10.2 | $3.3 |

| 2009 | $15.4 | $8.4 | $3.6 | $2.9 | $10.6 | $3.3 |

| 2010 | $14.4 | $8.5 | $3.8 | $3.0 | $10.6 | $3.5 |

| 2011 | $17.4 | $9.8 | $4.5 | $3.2 | $11.1 | $3.7 |

| 2012 | $21.0 | $10.4 | $4.3 | $3.4 | $11.7 | $3.7 |

| 2013 | $23.0 | $10.1 | $4.4 | $3.6 | $12.0 | $4.0 |

| 2014 | $21.4 | $13.5 | $5.0 | $3.5 | $12.0 | $4.0 |

| % Change | 171% | 111% | 6% | 59% | 48% | 48% |

| Source: Statistics Canada CANSIM Table 002-0044 Agricultural Taxation Data (unadjusted) | ||||||

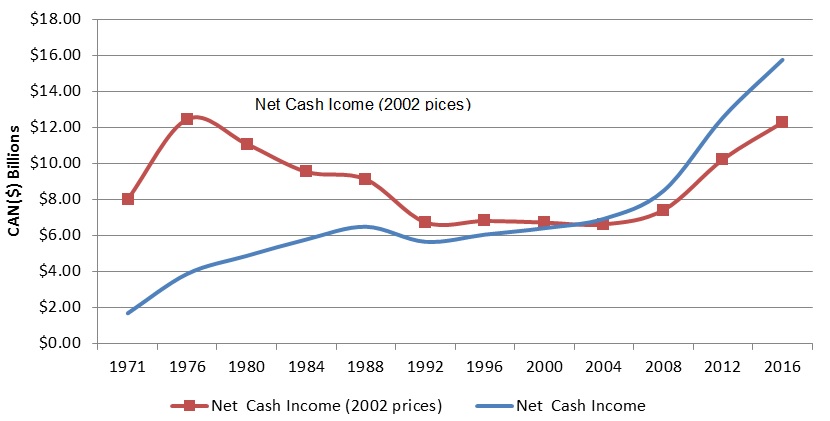

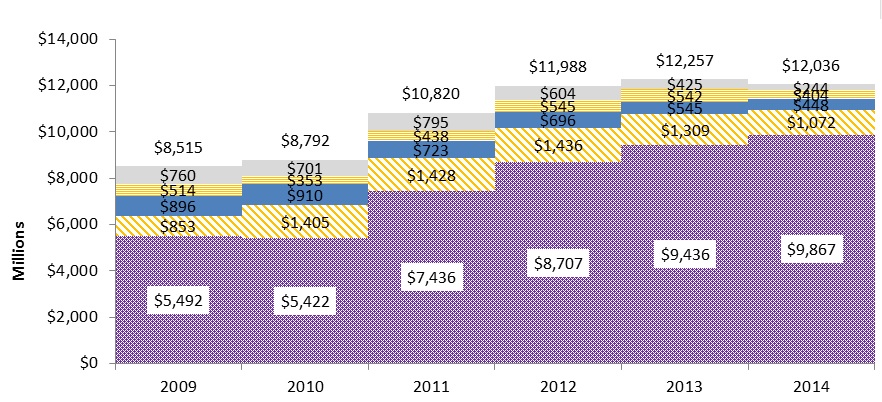

Gains in revenues have contributed to record levels of profitability of farmers. Net Cash Income (NCI), a measure of the aggregate profitability of the agriculture sector, reached a record of $15.2 billion in 2015, the highest level in real terms since the 1970s (Figure 1). Producers were protected by the rapidly depreciating Canadian dollar but this situation is not expected to continue over the short term. Net cash income is forecast to decline by two percent in 2016 and by another seven percent in 2017, led by an expected drop in commodity prices.

Description of above image

Figure 1 illustrates the historical trends for net cash income in $billions both in general and in 2002 prices for the years 1976 to 2016.

| 1971 | 1976 | 1980 | 1984 | 1988 | 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Cash Income | 8.02 | 12.46 | 11.08 | 9.54 | 9.12 | 6.73 | 6.81 | 6.72 | 6.62 | 7.41 | 10.23 | 12.28 |

| Net Cash Income (2002 prices) | 1.68 | 3.87 | 4.87 | 5.78 | 6.49 | 5.65 | 6.05 | 6.41 | 6.93 | 8.48 | 12.56 | 15.76 |

Source: AAFC (2016). 2016 Canadian Agricultural Outlook, Chart 3a.

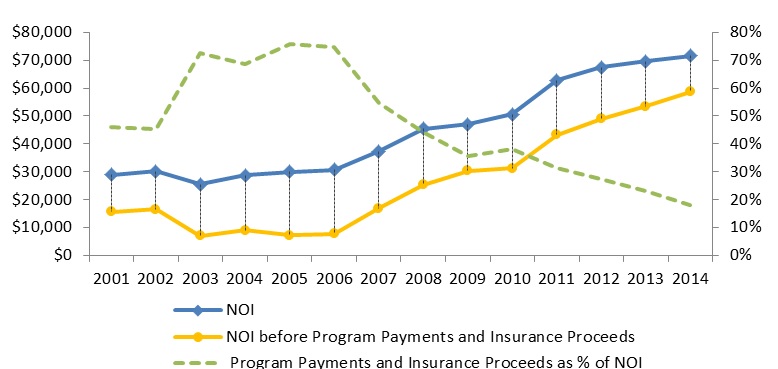

Total Net Operating IncomeFootnote 8 (NOI), a measure of the profit or loss of an average farm operation, more than doubled from $5.8 billion in 2004 to $15.2 billion in 2015. The average NOI per producer grew by just over 170 percent from $28,784 in 2004 to $78,795 in 2015 and is forecasted to decline to a record high of $77,923 in 2016 and to $73,486 in 2017.Footnote 9

Net Operating Income as a percentage of total operating revenues, a measure of a farm operation’s profitability ratio, grew from 14 percent in 2004 to 18 percent in 2015 as market revenues increased faster than operating expenses. As illustrated in Figure 2, profitability ratios were highest among grains and oilseeds, supply managed commodities and fruit, vegetable and potato producers and lowest for cattle and hog producers.

Description of above image

Figure 2 illustrates the operating profit margins by major commodity from 2004 to 2014

| Year | Grains and Oilseeds | Cattle | Hogs | Fruit, Vegetable and Potato | Supply Managed Commodities | Greenhouse Nursery and Floriculture | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 17.3% | 7.9% | 9.0% | 12.4% | 18.9% | 8.9% | 13.7% |

| 2005 | 15.4% | 6.8% | 11.5% | 14.2% | 20.9% | 9.2% | 13.4% |

| 2006 | 17.1% | 4.8% | 6.2% | 15.3% | 19.4% | 10.0% | 12.6% |

| 2007 | 20.5% | 5.4% | 6.5% | 15.4% | 19.1% | 8.4% | 13.8% |

| 2008 | 24.3% | 6.2% | 2.3% | 14.3% | 17.9% | 8.7% | 15.1% |

| 2009 | 24.6% | 5.0% | 2.8% | 14.1% | 17.8% | 10.8% | 15.5% |

| 2010 | 23.7% | 5.3% | 5.5% | 14.3% | 20.7% | 110% | 16.1% |

| 2011 | 27.9% | 4.9% | 5.4% | 14.9% | 21.0% | 9.6% | 17.6% |

| 2012 | 27.1% | 5.7% | 6.2% | 15.1% | 20.0% | 9.0% | 18.0% |

| 2013 | 26.4% | 4.4% | 6.0% | 15.3% | 19.8% | 11.9% | 17.8% |

| 2014 | 23.9% | 7.3% | 11.9% | 15.4% | 20.6% | 12.2% | 17.9% |

Source: Statistics Canada Agricultural Taxation Data Canadian Socio-economic Information Management Table 002 0044

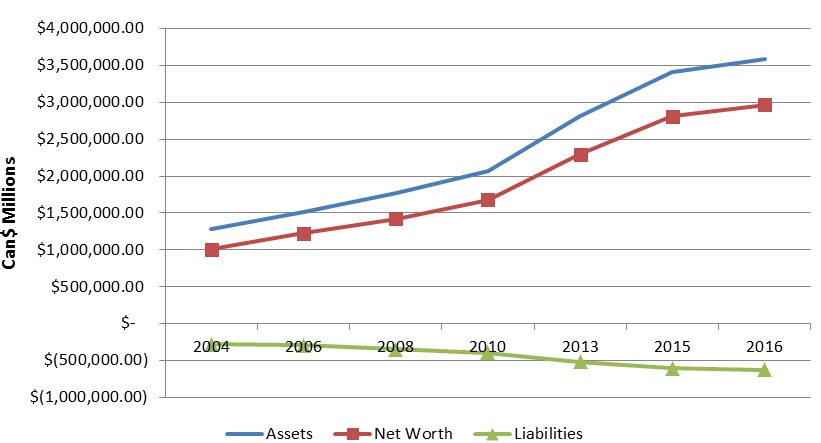

As a result of recent increased revenues and profitability, farm financial measures have been positive. Balance sheets are strong with net worth increasing year over year. In 2015, the average Canadian farm is forecasted to have $3.2 million in assets and $580 thousand in debt, for an overall net worth of $2.3 million.Footnote 10 The average net worth of a Canadian farm is forecasted to increase to $2.7 million in 2016 (Figure 3).Footnote 11

Description of above image

Figure 3 illustrates the trend in average assets, liabilities and net worth of Canadian farms in millions of dollars per year for the years 2004 to 2016

| 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 1,283,878 | 1,517,909 | 1,773,501 | 2,073,377 | 2,806,584 | 3,413,185 | 3,585,876 |

| Net Worth | 1,005,704 | 1,224,009 | 1,423,532 | 1,681,253 | 2,293,605 | 2,809,426 | 2,963,230 |

| Liabilities | −278,174 | −293,900 | −349,964 | −392,124 | −512,975 | −603,759 | −622,646 |

Source: AAFC (2016). 2016 Canadian Agricultural Outlook, Chart 6a.

Farmers have access to capital to meet short-term financial obligations and make investments in their farming operations. For example, in 2014/15, Farm Credit Canada approved 47,178 new loans with an average loan value of $178,825 and the Canadian Agricultural Loans Act Program approved 1,569 new loans.Footnote 12 According to the interest coverage ratio, a measure of how many times a farm could pay its current interest payment with its available earnings, the average Canadian farm operation is capable of paying its interest payments 11 times over.Footnote 13 The 2013 Farm Financial Survey reported that 83 percent of farms with revenues of $250,000 or greater, responsible for 88 percent of all agricultural sales, were under no financial stress (Figure 4).Footnote 14

Description of above image

Figure 4 illustrates the financial stress levels of farms with revenues greater than $250,000 in 2013

| Cash Flow Categories | Less than 50% | 50% to 75% | Greater than 75% | All equity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than $30,000 | 3% or 4% of total agricultural sales (significant financial stress) | 4% or 3% of total agricultural sales (significant financial stress) | 7% or 4% of total agricultural sales (moderate financial stress) | 14% or 10% of total agricultural sales |

| $30,000 to $60,000 | 1% or 1% of total agricultural sales (significant financial stress) | 2% or 1% of total agricultural sales (moderate financial stress) | 3% or 2% of total agricultural sales (no financial stress) | 6% or 4% of total agricultural sales |

| Greater than $60,000 | 6% or 11% of total agricultural sales (no financial stress) | 18% or 21% of total agricultural sales (no financial stress) | 56% or 42% of total agricultural sales (no financial stress) | 80% or 74% of total agricultural sales |

| All Cash Flow | 10% or 15% of total agricultural sales | 24% or 25% of total agricultural sales | 66% or 48% of total agricultural sales | 100% or 88% of total agricultural sales |

Source: AAFC (2016). Overview of Farm Financial Situation in Canada (2013 Farm Financial Survey, AAFC calculations)

Ongoing and cyclical risks facing the agriculture sector

Despite the strong performance of the Canadian agriculture sector in recent years, the sector continues to face a wide range of production, marketing and business risks:

- Production risks can negatively impact planting and harvesting of crops, farm yields and crop quality, and producers’ ability to raise livestock. For example, crop producers face weather-related risks associated with unseasonably cold weather, drought or excess moisture and lack of heat, as well as long-term risks associated with global warming including changing weather patterns and insect and disease ranges pushing north. Livestock producers also experience production risks through weather-related impacts on forage and pasture production and animal health risks. These major weather events and animal and plant diseases are an ever-present reality and are generally beyond the control of producers and severely impact farm production and income.

- Market and price risks can negatively impact production levels and/or profit margins. As Canada is a major exporter of many agricultural commodities, prices are determined in large part by the global market. Producers are subject to changes in market prices resulting from supply and demand fluctuations including the emergence of competition from agricultural producers in other countries and changing consumer preferences, variable transportation costs and currency exchange rates. Transportation barriers and tariff and non-tariff barriers can also have a very detrimental impact. Examples include loss of trade due to animal health risks such as foot and mouth disease and avian influenza; delayed transportation of grain to domestic and export customers or delayed transportation of perishable horticulture commodities; public resistance leading to market closures for genetically modified foods; and border/market closures due to food-borne contaminants.

- Producers face input cost volatility, due to fluctuating fuel, fertilizer, feed and labour costs and land prices.

- Business risks include insufficient access to credit and inadequate cash flow. These can force producers to market at depressed prices to make interest payments or meet operating expenses and make them particularly vulnerable to short-term income losses and market and price risks.

- Lastly, policy risks associated with changing government policies and programs and regulations are only imperfectly predictable by farmers. Examples include changing levels of coverage or support provided by government programs, and changes in environmental and food safety regulations requiring capital investments.

Many of these price and market risks are cyclical in nature and the production risks associated with weather, diseases and pests are ongoing. For example, the 2016 BRM Survey findings show that during the next five years, two-thirds of surveyed producers expect to face risks associated with weather (63%), almost one half expect risks due to rising input prices (48%), and approximately one third anticipate risks associated with changing government policies and programs (33%), currency fluctuations (32%), decreasing output prices (28%) and market disruptions (26%). Nearly a quarter anticipate risks due to disease or pests (21%) and 10 percent expect credit risks.

The findings of the literature review and interviews with some key informants also suggest factors such as climate change, increased trade and export dependence, border closures, greater competition from developing export countries, and increased specialization may intensify the risks faced by producers in coming years.

Inadequacy of private and producer-led tools and supports

Available private sector and producer-led tools and support mechanisms are insufficient on their own to help producers manage the above listed risks and to remain competitive nationally and internationally:

- No private insurers or other institutions are currently involved in the delivery of multi-peril production insurance in Canada. The inability of the private sector to provide multi-peril production insurance at reasonable premiums is attributed to insufficient information related to the risk, which prevents a probable distribution function from being accurately calculated and actuarial odds established, and the limited ability of private insurers to pool risk across individuals. The unavailability of accurate information can occur for a variety of reasons such as lack of data on rare non-systematic risks or inability of producers to share information with insurance agents. The inability to pool risk across individuals is the result of production risks which are likely to impact a large percentage of individuals, such as a weather related disaster that will impact the yield of all or a large number of producers resulting in large losses. In these instances, the size of the expected loss results in high premiums.

- Few private insurance products for livestock/animal disease have been developed. This is the result of a lack of significant demand for coverage on the part of producers; a lack of knowledge/data for analyzing the risks inherent in agricultural activity; and a lack of capacity for developing tools. In addition, the lack of involvement by the financial sector has been attributed to the recognition that the costs associated with researching livestock insurance risks outweigh the expected gain of developing a livestock insurance product.

- Futures, forward contracts and marketing contracts are used by fewer than 25 percent of Canadian producers.Footnote 15 The resources and level of investment expertise required for dedicated product marketing using these tools makes them inaccessible to many smaller producers. Availability also varies by sector.

- Expansion of farm operations can help mitigate risk but often requires large-scale investments which may be outside the reach of smaller farms or those with high debt to asset ratios.

- Diversification can be effective in mitigating risk, particularly price risk, but is increasingly expensive due to the capital intensive nature of modern farming and benefits from economies of scale, making it uncommon among large producers. Diversification strategies also do not adequately protect households in a major disaster that affects all sources of farm incomes, as households are likely to experience losses to both cash crops and subsistence crops.

- Off-farm employment income is an effective risk mitigation strategy, particularly for smaller farms; however, this is primarily seen by the majority of farm households as a way of increasing household cash flow rather than a risk management strategy.

3.1.2 Role of the Business Risk Management programming

Due to the inadequacy of private sector and producer-led tools and support mechanisms, there is a continued need for the BRM programs to help producers manage exceptional risks associated with severe market volatility and disaster situations. Positive market conditions, record profitability and structural transformations resulting in the dominance of the sector by larger, more sophisticated farms have all significantly contributed to greater capacity among producers for managing normal business risk. The appropriate role of the BRM programming is to provide disaster level support and encourage producers and the private sector to develop tools and strategies to manage normal business risk. This is in line with best practices identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Evidence of producers’ capacity to manage normal business risks

The capacity of Canadian agricultural producers to manage normal business risks (such as, small or frequently occurring losses due to normal variations in production, prices and weather) has increased significantly. This is due in part to recent positive market conditions and record profitability that have prevailed for much of the past decade. As described previously, the recent economic state of the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector is very positive. Producers, on average, are enjoying robust balance sheets and high profitability, have access to capital to meet short-term financial obligations and to make on-farm investments, and are not experiencing financial stress. As a result, there has been less need for BRM programming to assist producers in managing small, frequently occurring losses.

Structural transformations have also led to the domination of the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector by larger, more sophisticated farms with greater capacity for managing normal business risk:

- Technological and genetic advancements including more sophisticated monitoring and measuring technology, the development of sophisticated seeding equipment, guidance and auto-steering equipment and larger planting and harvesting equipment are all contributing to increased crop yields and productivity. Livestock productivity has also increased as a result of genetics, technological improvements, improved feed formulations and other improved management practices.Footnote 16

- The number of large, highly specialized operations has increased to capture economies of scale in response to competition from low-cost exporters, rising input prices and declining operating margins. Between 1951 and 2011, the number of farms in Canada declined by almost two-thirds from over 600,000 to approximately 206,000 while the number of acres farmed remained approximately the same.Footnote 17

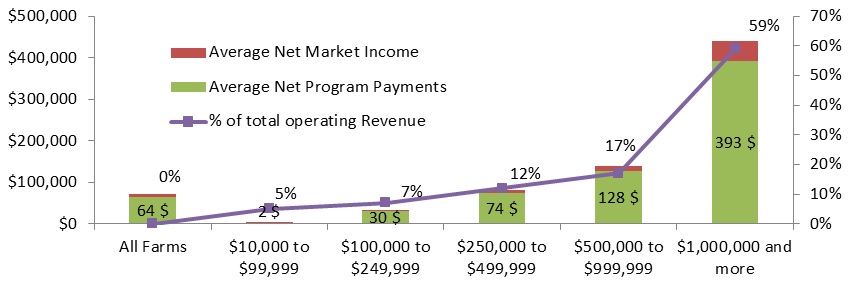

Large farms have a greater capacity for managing normal business risks. Farms with revenues of $500,000 or more have considerably higher net incomes than smaller farms (Figure 5). The average net market income (such as, before program payments) of farms with revenues of $1 million or more was about $393,000 compared to an average net income of $30,000 for farms with revenues between $100,000 and $249,999.

Description of above image

Figure 5 illustrates the net market incomes of Canadian farms by revenue class in 2014

| Revenue Class | Average Net Program Payments | Average Net Market Income | % of total operating Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Farms | $7,000 | $64,000 | N/A |

| $10,000 to $99,999 | $1,000 | $2,000 | 5% |

| $100,000 to $249,999 | $4,000 | $30,000 | 7% |

| $250,000 to $499,999 | $7,000 | $74,000 | 12% |

| $500,000 to $999,999 | $12,000 | $128,000 | 17% |

| $1,000,000 and more | $48,000 | $393,000 | 59% |

Source: AAFC (2015). Farm Financial Conditions and Government Assistance Data Book 2014

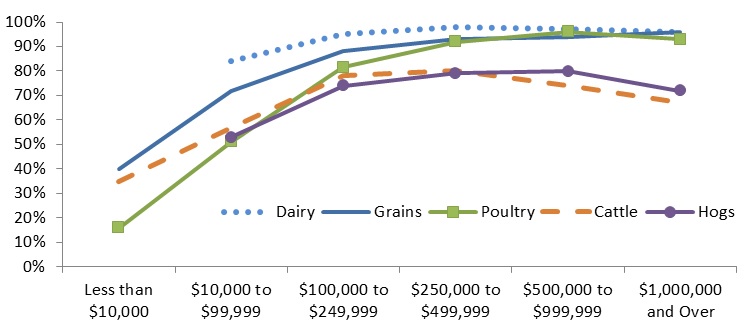

Large farms are also more consistently profitable. For most commodities, farms need to reach at least $250,000 in sales to have a high probability of being profitable (Figure 6).

Description of above image

Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of farms in each major sector that break even by revenue class, including program payments, for the years 2009-2013.

| Less than $10,000 | $10,000 to $99,999 | $100,000 to $249,999 | $250,000 to $499,999 | $500,000 to $999,999 | $1,000,000 and Over | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy | 84% | 95% | 98% | 97% | 96% | |

| Grains | 40% | 72% | 88% | 93% | 94% | 96% |

| Poultry | 16% | 51% | 82% | 92% | 96% | 93% |

| Cattle | 35% | 57% | 78% | 80% | 74% | 67% |

| Hogs | 53% | 74% | 79% | 80% | 72% |

Source: Statistics Canada Census of Agriculture and AAFC Canadian Agriculture Dynamic Micro-Simulation Model (CADMS)

Large farms with revenues over $500,000 are also responsible for the majority of capital investments and are more likely to have the expertise and dedicated resources required to make use of private sector risk management tools such as futures, forward contracts and marketing contracts.

As larger farms are characterized by greater use of more sophisticated risk management technologies and practices, increased access to capital investment for risk mitigation measures, increased specialization and higher and more consistent profitability, the increasing domination of the sector by large farms has further reduced the need for the BRM programming to support coverage of normal business risks.

Appropriate role of Business Risk Management programming

The appropriate role of the BRM programming is to provide disaster level support and encourage producers and the private sector to develop tools and strategies to manage normal business risk. The role of BRM programming is to also encourage producers to adopt best practices and take actions to manage risk.

A 2011 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report examining the role of governments in agricultural risk managementFootnote 18 suggested government support should focus on infrequent but catastrophic events such as severe and widespread weather events or the outbreak of a highly damaging disease that affect many or all farmers over a wide area and will usually be beyond farmers’ or markets’ capacity to cope. According to the report, clearly defined coverage levels and procedures, and roles and responsibilities between government and producers are needed to manage pressures for ad hoc support and avoid creating moral hazard where producers fail to take precautions or risk mitigation efforts in the belief that government assistance will provide sufficient coverage or will step in following a loss. Best practices for governments identified by the OECD include facilitating good start up conditions for the development of market-based tools and supports, taking a holistic approach to risk management by assessing all risks and their relationship to one another, and not providing support for normal business risk beyond encouraging and educating producers to assess and develop their own risk management strategies.

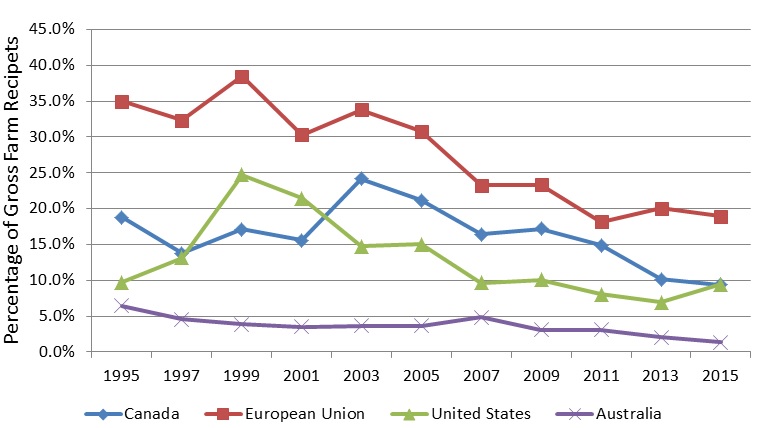

The transition from covering normal business risks to targeting support towards disaster risk coverage is in line with trends in government agricultural support in other developed economies. The 2015 OECD Agricultural and Monitoring ReportFootnote 19 revealed that the relative cost of agricultural support, as a percentage of total gross domestic product (GDP), has declined in Canada as well as in other comparable jurisdictions (for example, the United States, Australia and the European Union); however, Canada’s support for producers, as a percentage of gross farm receipts, remains higher than that of Australia. These findings were corroborated by a 2014 comparison undertaken by the BRM working group in support of GF2, which found that Canada’s producer support is similar to the United States and that European Union (EU) reforms are narrowing the gap with Canada (Figure 7).Footnote 20

Description of above image

Figure 7 compares the producer support estimates as percentage of gross farm recipients for Canada, United States, the European Union and Australia by year for the years 1995 to 2015:

| 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 18.8 | 13.76 | 17.11 | 15.61 | 24.19 | 21.18 | 16.43 | 17.2 | 14.88 | 10.13 | 9.4 |

| European Union | 34.95 | 32.34 | 38.49 | 30.28 | 33.78 | 30.76 | 23.24 | 23.35 | 18.19 | 20.06 | 18.92 |

| United States | 9.74 | 13.13 | 24.73 | 21.43 | 14.74 | 15.04 | 9.67 | 10.1 | 8.01 | 6.9 | 9.44 |

| Australia | 6.43 | 4.58 | 3.86 | 3.5 | 3.66 | 3.64 | 4.83 | 3.09 | 3.12 | 2.06 | 1.34 |

Source: AAFC (2016), Business Risk Management: Considerations for the Next Policy Framework, Slide 4. 2015 numbers are forecast

3.1.3 Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Growing Forward 2 priorities and Business Risk Management principles

AgriInsurance, AgriStability and AgriInvest are aligned with federal roles and responsibilities legislated in the FIPA. The Wildlife Compensation Program is somewhat aligned with federal responsibilities, as there is a weak policy rationale for providing compensation for non-federally protected species. AgriInvest and the Wildlife Compensation Program are less aligned with GF2 priorities and BRM principles due to their design as entitlement programs that primarily cover or compensate for normal business risks. Some AgriInsurance products covering some normal risk are less aligned with GF2 strategic priorities and the appropriate role of BRM programming.

Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

AgriInsurance, AgriStability and AgriInvest are aligned with federal roles and responsibilities. The programs are legislated under Section 4 of FIPA, which authorizes the Minister to enter into an agreement with one or more provinces for the establishment of a crop insurance program and to establish programming with the provinces for the protection of producers’ income.Footnote 21

Section 4 of FIPA outlines three core BRM principles:

- Compatibility with Canada’s international obligations (compliance to trade commitments and minimizing countervail risk);

- Not unduly distorting production or marketing decisions (minimizing moral hazard); and

- Providing equitable treatment across commodities and regions.Footnote 22

The Wildlife Compensation Program is only somewhat aligned with federal roles and responsibilities. Because the predecessor Waterfowl Program was included in the provinces’ crop insurance agreements in 1991, the Wildlife Compensation Program was originally legislated under Section 4 of FIPA.Footnote 23 In subsequent iterations of the agricultural risk frameworks, the Program has been administered as a compensation companion program under the Production Insurance program base in most provinces.

The Wildlife Compensation Program is aligned with federal roles and responsibilities to compensate producers for losses resulting from damage caused by waterfowl species protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act and the Canada Wildlife Act. Québec is the only province to use the program to compensate for legislated species. There is no federal responsibility or policy rationale for the compensation provided to producers in other provinces for spot losses resulting from species other than the waterfowl species protected under federal legislation.

Alignment with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Growing Forward 2 strategic outcomes, priorities and objectives

The four BRM programs support the strategic outcomes of AAFC and the GF2 policy framework for a competitive and innovative sector that contributes to society’s priorities and is proactive in managing risk.Footnote 24,Footnote 25 The programs are also aligned with key policy outcomes of GF2, which include a greater ability for producers to stabilize their enterprise income through a wide range of financial tools and effective coordinated responses to disasters, should they occur.

From GF to GF2, the objectives of the agricultural framework were revised to target government support to more severe and catastrophic losses and encourage producers to manage more normal business risks.Footnote 26 This shift in priorities was reflected in reforms to AgriStability and AgriInvest:

- AgriStability underwent three changes:

- Elimination of tiered coverage and a reduction in the coverage threshold. Under GF, producers were eligible to receive payments of 70 percent of the loss for margin declines of 15 percent to 30 percent (Tier 2), and payments of 80 percent of the loss for margin declines of 30 percent or greater (Tier 3). Under GF2, producers are eligible to receive payments covering 70 percent of the loss for margin declines of 30 percent or greater only.

- Adoption of a reference margin limiting factor (RML). To avoid compensating producers for reduced profits rather than income losses while maintaining disaster level coverage, the lower of the Olympic average reference margin or the producer’s eligible expenses for the reference years is used as the reference margin in the payment calculation.

- Increase in the negative margin payment from 60 to 70 percent. Under GF, a producer experiencing a negative margin (such as, the allowable expenses plus the value of the inventory change exceed the allowable income) was eligible to receive an AgriStability payment for 60 percent of that portion of the loss. Under GF2, producers experiencing a negative margin are eligible to receive a payment covering 70 percent of the loss.

- The AgriInvest payment rate was reduced from 1.5 to one percent of allowable net sales (ANS), thereby reducing the government maximum contribution from $22,500 to $15,000, and the maximum account balance was increased to 400 percent of ANS to allow the funds to respond to larger losses or investments.

No changes were made to AgriInsurance or the Wildlife Compensation Program under GF2:

- A 2014 AAFC examinationFootnote 27 of AgriInsurance determined that the program is a very successful tool in managing production losses for both producers and governments and that it is seen as predictable and bankable. Consequently, no changes were recommended.

- A review of the Wildlife Compensation Program was undertaken by a special federal/provincial task force in 2013 that provided an in-depth examination of possible program changes. As no national consensus was reached in time for program changes to be incorporated under GF2, discussions of the recommended changes will continue to support changes for the Next Policy Framework.

As no other changes were made to the design of AgriInvest as an entitlement program that primarily covers or compensates producers for normal business risks, the program is less aligned with GF2 priorities and objectives. Elements of the program’s design are also less aligned with BRM principles. For example, because AgriInvest matching contributions are based on one percent of a producer’s ANS, program benefits are related to sales revenues rather than income loss or need for funding.

The Wildlife Compensation Program is designed as an entitlement program providing compensation primarily for normal business risks, and is consequently less aligned with GF2 priorities and objectives and BRM principles. The program is different than AgriInsurance because producers do not pay premiums to participate in the Wildlife Compensation Program while they pay annual premiums to participate in AgriInsurance. As a result, producers do not contribute to the costs of the Wildlife Compensation Program.

Additionally, the scope of the mitigation and prevention plans in place is not well documented. While all participating provinces can demonstrate some type of program or service to assist producers in reducing their agricultural losses, or a requirement that producers use available mitigation strategies to prevent losses, mitigation or prevention strategies for particular crops or wildlife are not tracked. Thus, it is not evident to what extent producers are required to demonstrate the use of prevention or risk mitigation strategies to prevent recurring losses. Requests from provincial governments for evidence regarding the types of prevention and mitigation efforts taken by producers to prevent recurring losses were not fulfilled during the evaluation.