Close your eyes and imagine a farmer’s field at harvest time. What do you see?

Considering the amazing diversity of Canadian agriculture and food, there are a lot of possible answers, from apples to zucchini. Still, what you imagine first is probably a picture of golden wheat, swaying in the wind with the promise of a good harvest.

Wheat is part of the cereal family, the most widely-consumed of all cultivated crops. It’s a staple food around the world thanks to its high nutritional value, easy access by human stomachs, and because it’s also quite pleasing to the tongue. When it comes to the foods that sustain us from year to year, wheat’s kind of a big deal. Ever since humans turned the first grains of wheat into a loaf of bread, they’ve been trying to protect this vital plant and help it grow to its full potential. So it’s not surprising that wheat research is one of the most vibrant fields of plant pathology, the study of plant diseases.

Canada has a rich history of studying cereals. The need for a better strain of wheat was one of the main reasons Members of Parliament passed the Experimental Farm Act in 1886, establishing the cross-country network of AAFC research stations that still exist today. After passing this act, no one could have imagined that all someone needed for a good crop was a pair of walking boots, a mouth, and an immense amount of patience.

The family business

What is plant breeding?

Plant breeding is the science of breeding plants, or “crossing,” and selecting their offspring for new and improved types, or “varieties.” Plants can be bred to grow and mature in a specific environment, to resist diseases or even to have qualities that make them more useful to us—like making a good loaf of bread. Plant breeders choose the parent plants, taking the pollen (male) from one plant and putting it on the pistil (female) of another plant. The resulting seed, containing DNA from both parents, hopefully ripens with the intended inherited characteristics, or “genetic traits.” Seeds are grown over several generations of selecting, harvesting and testing until the resulting plant has the optimal traits. This whole process can take up to 12 years!

In the late 1800s, William Saunders, Canada’s first director of agricultural research, knew that the key to wheat’s success was finding a variety that could thrive on the expansively fertile and flat land of the Canadian Prairies. On his small family farm outside of London, Ontario, he honed the science of plant breeding to find a worthy candidate, a skill that he passed onto his children, one of whom was none other than Charles Saunders.

Though Charles initially intended on becoming a musician, his father strongly believed a career in science would be a better use of his talents. Percy Saunders, Charles’ brother, was already working with research stations across the country to develop better wheat varieties, finding success in 1892 by crossing early-ripening “Hard Red Calcutta” (a wheat variety from India) with “Red Fife,” a variety that was the milling standard for spring wheat in Ontario. One of the results was Markham, a wheat variety that grew well in the Prairies but didn’t last more than a few seasons. There was a piece missing—one that perfectly blended abundance, resilience and staying power. And Charles was going to play a vital role in its development.

Until the re-discovery of the laws of inheritance (the theory of how parents pass genetic characteristics to offspring) in 1900, researchers at the time knew little about genetic traits and dominant and recessive genes. Charles learned of it at the first North American Plant Breeding conference in 1902 and immediately incorporated the theory into his work. He quickly saw for himself the value of re-selecting (choosing specific plants) and genetically purifying old varieties (removing unwanted traits from plants). Coupled with his meticulous note-taking and ease in working with his hands, he became an experimentalist and then a cerealist at Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm in 1905.

Today, laboratories are full of sophisticated equipment for researchers to measure the baking quality of new wheat varieties. But when Charles was conducting his field trials in the early 1900s he had access to virtually no equipment, not even a mill to grind seeds into flour or an oven to bake test batches of bread.

Not the least bit discouraged, Charles devised a brilliant tool to test the new wheat varieties he was creating… his mouth!

A taste of success and nobility

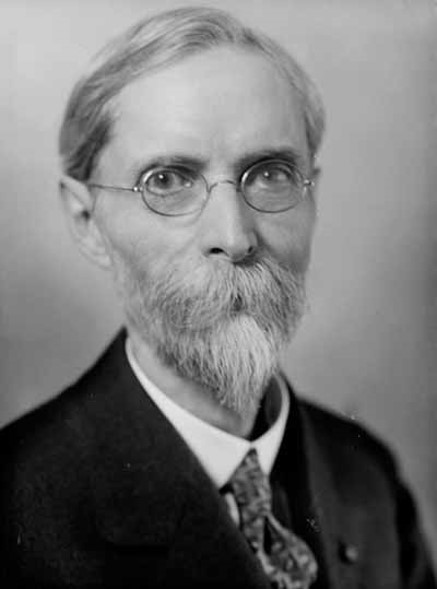

Charles Saunders

In the fields of Ottawa’s Experimental Farm, Charles got down to work by growing rows and rows of past wheat varieties. When the plants matured, he’d select a single wheat head from each row that had the desired physical traits. During the winter months, he’d chew the wheat kernels from his selections, evaluating the amount of gluten “gum” they created. If the gum was sticky and held together well under the heat of his chewing, it was a good candidate, and that line would be regrown the following season.

For years on end, Charles chewed and recorded and chewed some more. He spent upwards of fifteen hours a day in the field and his office, even forgoing visitors in favour of his work. This dedication eventually led to a discovery that would change the face of farming forever.

In 1904, Charles began working with Markham wheat, the variety his brother Percy had created during his time at Saskatchewan’s Indian Head Research Farm. After several years of selecting, chewing, growing, re-selecting and repeating, he finally created a wheat that connected all the missing pieces.

Charles dubbed it, “Marquis wheat.”

Marquis had all of the qualities of the best wheat varieties: it had a high yield, impressive baking potential, and ripened about two weeks earlier, perfect for the new farmlands of the Prairies. But most importantly, because Charles had followed the laws of inheritance, the plants consistently grew with the same hardy qualities year after year.

It was the breakthrough farmers needed, and Charles rushed to get seeds into their hands. The excellent milling and baking qualities of Marquis were undeniable, and farmers enthusiastically embraced this Canadian innovation. By 1918, Marquis wheat was planted on an astounding 20 million acres of farmland stretching from Nebraska to Saskatchewan.

Charles’ experiment was a triumph. It unlocked the wheat production gates in the Prairies, and set Canada on the path to becoming a cereal superpower. Not only did Marquis wheat provide a vital new source of food and income for the country, but its discovery had other far-reaching impacts.

Legends live forever

Charles Saunders sits in a field of wheat

The engineers behind the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway had already seen the need for a cross-country rail line that could move agricultural products from farm to port. Thanks to Charles’ discovery, the rails were now ready to route millions of wheat bushels to Canadians both at home and abroad. During the First World War’s pivotal year of 1915, Marquis made up 90% of the wheat shipped from Canada to France. This was an essential contribution to the war effort, as shipping routes from Argentina and Australia had been cut off completely. In 1948, the British High Commissioner to Canada told an audience in Ontario that “without the help of Canadian farmers, Britain would have lost the [First World] War in fewer than two years.”

Fast forward to today: all bread wheat varieties cultivated in North America can be traced back to Marquis wheat. This agricultural legacy stands as a testament to the pioneering work of Charles Saunders, whose dedication and ingenuity laid the foundation for a flourishing wheat lineage and, most importantly, for keeping our bellies full.

Despite the monumental impact of his work, Charles never really got the widespread recognition he deserved. He carried on as he always had, conducting research and publishing it for the benefit of farmers everywhere. In 1934, he was knighted and became Sir Charles Saunders, but he never became a household name. History has always shed its brightest light on those larger-than-life figures, the wagers of war and bringers of peace, the great speakers and leaders. Isn’t there room for a soft-spoken plant breeder in muddy boots?

But perhaps this is fitting. Charles was most at home with farmers, who will always recognize one of their own. No one would begrudge them the right to keep this most Canadian of heroes all to themselves.

Get more Agri-info

- Want more stories like this? Explore what else Agri-info has to offer.

- Interested in reporting on this story? Contact AAFC Media Services at aafc.mediarelations-relationsmedias.aac@agr.gc.ca to arrange an interview with one of our experts.