Table of Contents

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Introduction

- 3. What We Heard

- 4. Next Steps

- Annex A: Original SAS Vision and Goals from SAS Discussion Document

Acknowledgements

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) gratefully acknowledges the support from the Intersol Group in implementing the producer, stakeholder, and other engagement workshops, and their contribution to this report.

1. Executive Summary

In December 2022, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada started consultations with stakeholders, producers, and partners across the country to inform the development of a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy (SAS). The SAS will help set a shared direction for collective action to improve environmental performance in the sector and support farmer livelihoods and the long-term business vitality of the sector. Broad engagement is essential for ensuring the SAS identifies shared challenges, builds on past and current successes, enhances consensus among industry, and informs possible solutions as Canada works to strengthen the sector’s resiliency to climate change.

Feedback on the SAS was gained through over 400 responses to an online survey based on the SAS Discussion Document, 123 written submissions, four regional producer workshops, four virtual stakeholders workshops, self-led Indigenous workshops, and various virtual and in-person roundtables. Engagement on the SAS has continued throughout 2023 with Indigenous partners, provincial and territorial governments, and with the SAS Advisory Committee.

Through the engagement mechanisms, the following considerations were shared by participants that the Government of Canada should keep in mind when developing the SAS:

- The importance of applying an economic lens to ensure economic challenges and opportunities in the sector are reflected in order to support productivity, profitability, competitiveness, and producer livelihoods;

- Reflecting regional differences across the country in terms of varying strengths, needs, and opportunities;

- Recognizing early adopters as many producers have already led the path toward the adoption of environmentally sustainable beneficial management practices (BMPs) and technologies; and

- Improving data and measurement as there is a lack of consistency across agri-environmental data collection and analysis at the national, regional, and field levels.

The SAS Discussion Document outlined five priority issue areas (climate change mitigation, climate adaptation and resilience, biodiversity , water quality and quantity and soil health) and a set of five proposed goals for what the SAS should aim to achieve. There was general support from both stakeholders and producers of the draft goals; however, strong views were raised that an economic lens should be applied to all the goals. In regards to the five priority issue areas of the SAS, it was noted that they were often discussed in connection with each other, reflecting each issue’s complexity and interconnectedness. Finally, participants expressed the need to identify realistic targets that are achievable without threatening the productivity or profitability of farms.

Participants shared specific ideas on actions that are needed to advance sustainability in Canada’s agriculture sector, including:

- Direct and indirect financial incentives to increase the adoption of BMPs and technology — this was highlighted as the preferred approach by producers. Incentives need to be long-term and should consider the cost of adoption, return on investment and the value of ecological goods and services provided.

- Market based approaches — the SAS was noted as an opportunity to provide new standards and stimulate new partnerships and collaborations to enable markets to recognize and reward environmentally sustainable choices along the agri-food supply chain.

- Knowledge transfer and extension — ensuring that producers have the knowledge and information they need to adopt practices and technologies on their farm was a key theme noted by both producers and other participants – including on-the-ground support as well as peer-to-peer producer networks.

- Connections across the supply chain — while the SAS is currently focusing on the agricultural production level, the importance of influences further along the supply chain, including manufacturers, processors, retailers and consumers, was raised by participants.

- Indigenous food systems — stable access to agricultural lands to continue producing foods while also passing down knowledge to promote food security was considered crucial.

- Research and technology — there was strong support for more resources available for public research and applied research partnerships, in areas such as breeding programs, genetics and variety development for climate adaptation, and decreasing input use and increasing nutrient use efficiencies.

- Regulatory approaches — direct incentives were favoured over regulatory approaches to incentivize the adoption of BMPs. Nonetheless, some regulations were seen as more favourable than others.

- Broader and longer-term approaches — some participants noted Canada’s agricultural production should not be dependent on fossil fuels, citing both on-farm fuel use and inputs. Circularity, systems approaches, and supporting local and regional food systems were also highlighted.

Challenges with agri-environmental data and measurement was a key issue raised in consultations. At the national level, we heard concerns about how agriculture is modelled in the National Inventory Report, which represents Canada’s official accounting of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as reported to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. At a regional level, agri-environmental data is currently fragmented across the country, drawn from multiple sources, making it challenging to create comprehensive datasets that are valid and can inform decision-making. And at the local level, producers need tools to measure and collect data on their farms, helping them make production decisions and more informed investments. Overall, there was a strong call for a data strategy to collect, manage, and communicate data on GHG emissions, biodiversity, water, soil health and resilience, with solutions to address the data and measurement challenges developed with the sector and various stakeholders at different levels to effectively measure change.

The feedback and perspectives shared during the consultation process will support the development of the SAS. The Strategy is expected to be released in 2024.

2. Introduction

2.1 Background

Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector is a foundation of the Canadian economy, playing a vital role in producing food for Canada and the world. Producers have demonstrated notable improvement in environmental stewardship over the last 20 years, including enhancing soil health and doubling production while greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased only slightly. That said, Canada and the world are facing unprecedented challenges to produce and distribute more nutritious food in an environmentally sustainable manner while ensuring producers remain competitive and are able to sustain a secure livelihood. Market volatility, rising input costs, and food affordability all act as barriers in meeting global demand for food.

In December 2022, the Government of Canada launched consultations to develop a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy (SAS). The SAS will provide overarching guidance for collective action to improve environmental performance and coordinate action in the sector to 2050.

Engaging with producers, producer associations, industry groups, non-government organizations, federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) governments, and Indigenous groups provided valuable insight and feedback critical to understanding the challenges and opportunities in the sector and identifying effective solutions that support the support the SAS’ objectives.

2.2 Purpose of this report

This report presents a concise overview of the main viewpoints expressed by participants through the key consultation mechanisms for the SAS: an online survey; written submissions; virtual and in-person workshops; and Indigenous engagement. The report does not represent a consensus across all participants and points out where there are diverging perspectives. The report is structured around four key areas: considerations in developing the SAS, feedback on what the SAS should aim to achieve under the five priority areas, proposed actions to reach the SAS goals and outcomes, and issues related to data.

2.3 Overview of engagement

Description of the image above.

This figure provides an overview of the various consultation mechanisms undertaken as part of the development of a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy. This includes:

- Receiving 420 completed responses to a web-based survey;

- Receiving 123 written submissions;

- Establishing the Sustainable Agriculture Strategy Advisory Committee which launched in December 2022 and has met bi-weekly throughout 2023;

- Undertaking engagement with Indigenous Peoples including a self-led session by the Manitoba Métis Federation and organizing four regional focus groups with First Nation producers. Indigenous engagement is ongoing;

- Engaging with provinces and territories through bi-lateral discussions and existing federal-provincial-territorial committees;

- Engaging with producers across the country in four separate sessions: February 24, 2023 (BC, AB, SK), March 10, 2023 (MB, ON, YK, NWT, NU), March 20, 2023 (QC, NB, PEI, NS, NL), March 24, 2023 (all French speaking producers from across Canada), totaling 480 producers;

- Holding workshops with existing engagement tables: the Sustainability Sector Engagement Table, the Canadian Agricultural Youth Council, and the Canadian Food Policy Advisory Council;

- Holding four thematic stakeholder workshops with 291 participants in 2023 on goals and outcomes, data, and twice on approaches.

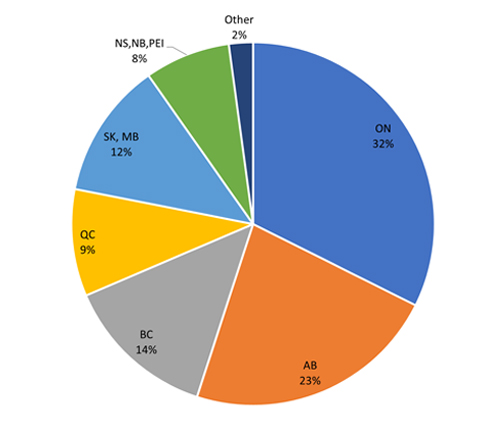

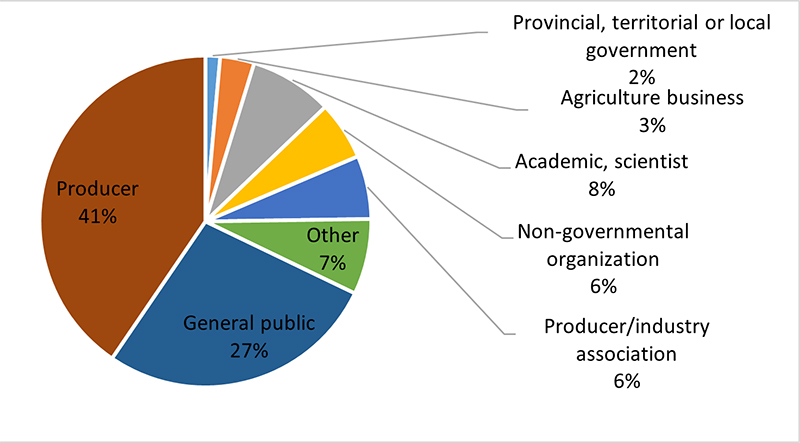

The SAS Discussion Document was published online in December 2022, along with a survey which was open until the end of March 2023. The survey included questions in three areas: what we should aim to achieve; approaches to advance environmental outcomes in the sector; and data. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) received 420 completed responses to the survey (Figures 1 and 2 display respondents by geographic location and type of respondent). In addition to the survey, AAFC received 123 written submissions. (see Figure 3 for breakdown by group).

Figure 1: SAS Survey Responses by Province and Territory (total 420)

Description of the image above.

A breakdown of Sustainable Agriculture Strategy consultation surveys respondents by province and territory: Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, other.

Data table:

| Province/Territory | Total Number of Survey Respondents |

|---|---|

| Ontario | 136 |

| Alberta | 95 |

| British Columbia | 57 |

| Quebec | 40 |

| Saskatchewan | 31 |

| Manitoba | 20 |

| Nova Scotia | 13 |

| New Brunswick | 11 |

| Prince Edward Island | 8 |

| Other | 9 |

Note 1, there were no completed survey responses from Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut or Newfoundland and Labrador.

Note 2, “other” refers to respondents who completed a survey and did not specify a province or territory, or who noted they were outside of Canada.

Figure 2: SAS Survey Respondents by Type of Respondent (total 420)

Description of the image above.

A breakdown of Sustainable Agriculture Strategy consultation survey respondents by type: provincial, territorial or local government, agriculture business, academic or scientist, non-governmental organization, producer or industry association.

Data table:

| Survey Respondent Type | Total Number of Survey Respondents |

|---|---|

| Provincial, territorial or local government | 6 |

| Agriculture business | 14 |

| Academic, scientist | 34 |

| Non-governmental organization | 24 |

| Producer/industry association | 26 |

| Other | 31 |

| General public | 115 |

| Producer | 170 |

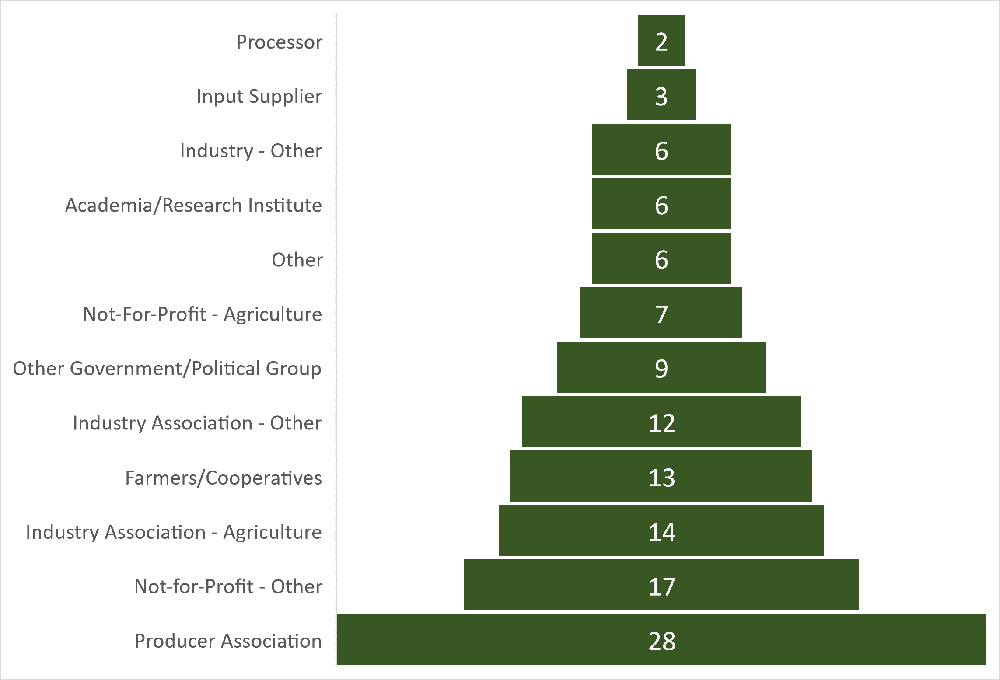

Figure 3: Number of written submissions received by type of respondent (out of 123)

Description of the image above.

A breakdown of Sustainable Agriculture Strategy written submissions received by type of respondent: processor, input supplier, industry-other, academia/research institute, agricultural not-for-profit, other, other government/political groups, industry association-other, farmers/cooperatives, industry association-agriculture, not-for-profit-other, producer association.

Data table:

| Written Submission Stakeholder Type | Total Number of Written Submissions |

|---|---|

| Processor | 2 |

| Input supplier | 3 |

| Industry — other | 6 |

| Academia/research institute | 6 |

| Agricultural Not-for-Profit | 7 |

| Other | 7 |

| Other Government/Political Group | 8 |

| Industry Association — other | 12 |

| Farmers/Cooperatives | 13 |

| Industry Association — Agriculture | 14 |

| Not-for-Profit — other | 17 |

| Producer Association | 28 |

In addition to the survey and submissions, a series of virtual and in-person workshops were held to gain input on the SAS. Four stakeholder workshopsFootnote 1 were organized around specific components of the SAS: goals and outcomes, data and measurement, and two workshops on approaches to reach SAS outcomes. Four virtual sessions with producers were held in different regions across the country. Engagement sessions were also held with the Sustainability Sector Engagement Table, the Canadian Food Policy Advisory Council, and the Canadian Agricultural Youth Council. Various ad hoc SAS roundtable discussions were also held serving as an opportunity to discuss the importance of advancing the sustainability, competitiveness, and vitality of Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector. Ongoing consultations are taking place with provincial and territorial partners (P/Ts) through bi-lateral conversations and through AAFC’s existing agri-environmental F/P/T working groups.

AAFC has begun to undertake engagement with Indigenous partners. This has entailed engaging in discussions about sustainable agriculture in general, as well as discussions on the SAS specifically. To date, the Manitoba Métis Federation has led a consultation with its citizens with a focus on the sustainable management of land and waters. Four regional focus groups were held with First Nations producers. Engagement with Indigenous partners will continue throughout and beyond 2023.

The SAS Advisory Committee was established at the start of the engagement period, co-chaired by AAFC and the Canadian Federation of Agriculture. It includes multiple sector stakeholders to facilitate two-way information sharing in the development of the SAS. The Committee was created to keep the agriculture and agri-food sector updated on the process of the SAS and to consider sector perspectives on specific approaches or actions to be included in the SAS. The Committee has a one-year term to December 2023, meeting on a bi-weekly basis, with the possibility of renewal in the new year.

3. What We Heard

3.1 Considerations for developing the SAS

Throughout the consultations, participants raised specific considerations and challenges that the Government of Canada should take into account in developing the SAS.

Importance of an economic lens for the SAS

How sustainability is defined was a key point of discussion, in terms of the need to consider and balance all three pillars of sustainability — environment, social, and economic — in the SAS. A clear message was shared throughout consultations on the importance of applying an economic lens to ensure the success of the SAS. We heard about how economic challenges and opportunities in the sector need to be reflected within the SAS to support productivity, profitability, competitiveness, and producer livelihoods.

Producers emphasized that the adoption of environmental practices or technologies need to make economic sense for their businesses. They also expressed that being environmentally sustainable cannot come before feeding their families, and adopting such practices or technologies must provide financial benefits for them to succeed. Participants shared that the adoption of beneficial management practices (BMPs) and environmentally sustainable practices can be capital intensive. Accessing capital can be difficult and even through cost-share programs, producers must pay up-front for technology or infrastructure that improves sustainability. Many practices take time to show a return on investment which can create additional financial burden for the maintenance and investments needed, particularly for small and medium-scaled producers. In addition, we heard that the next generation of young and new producers do not have the capital to invest in new practices or technologies. Overall, producers expressed that it is important for the government to share in the risks of sustainability efforts and provide financial incentives to support public goods or public data from farms.

Applying a social lens

The importance of community and human well-being and the need to incorporate a social lens in the SAS was also raised, including pressures on mental health and stress due to financial challenges and a lack of labour. Participants shared that more support needs to be given to the sector to encourage the transition of land ownership to a new generation of producers. Young and new producers are needed to enter the sector as older producers are set to retire; however, young and new producers are being discouraged and pushed out by high land and capital costs, and unstable profits. Issues were also raised about domestic food security and health in relation to food as well as worker health when using on-farm inputs, noting they need to be considered as part of a sustainable agricultural sector.

Regionality and diversity of sectors

A key theme that emerged from consultations was the need to recognize regional differences across the country in terms of varying strengths, needs, and opportunities. We heard that sustainability solutions or practices will not work across the country in the same way due to different climate conditions, soils, and landscapes. Producers suggested that regional and commodity specific research, technology, extension, and data would be most useful for them. Participants shared that the SAS should reflect differences across the country in terms of regions, farms, commodities, and production methods, and to tailor indicators, metrics, and targets to these differences. Ultimately, we heard that a one-size-fits-all approach will not work for advancing sustainability in the sector.

Scale of production

In addition to the diversity of regions and production approaches across the country, we heard about the differing challenges and needs of producers depending on their scale of operations. Large-scale producers were concerned around their ability to remain competitive and profitable in global markets, competing against producers from other countries with different policy and programming support from their respective governments. Other stakeholders emphasized the need to support a domestic market for sustainable food that is accessible and supportive of smaller-sized farms and local and regional food systems, while also being able to support international trade and exporting Canadian grown food.

Small-scale producers who participated in the consultation noted their financial struggles and inability to access government funding and programming for a variety of reasons including high cost-share ratios and disappearing local and regional infrastructure (for example, grain terminals and abattoirs) vital for their survival. Many producers also noted the increased amount of risk a small to medium scale producer takes on when trying a new practice or technology to increase sustainability on their farm, admitting that if that failed, with the marginal financial buffer many have, it could mean selling their farm and exiting the industry. Several producers also noted that some BMPs are appropriate at some scales and not others, and support for diverse approaches to sustainability on different sized farms should also be considered.

Need to recognize early adopters

We heard that producers who are early adopters of BMPs and technology want to be recognized and rewarded for the approaches they have been implementing on-farm to date. Many producers have already led the path toward adoption of environmentally sustainable BMPs and technologies, but feel that current government programming (for example, On-Farm Climate Action Fund) is not available to those who have already been implementing change.

Participants suggested that early adopters should be used as examples of success stories to encourage promoting adoption in the sector rather than penalizing them through the inability to access funding. Early adopters should be viewed as mentors and leaders setting an example to others. Some producers are hesitant to make big changes to their current practices and hearing successes could give them more confidence to adopt environmentally sustainable practices. Some examples of how early adopters can be recognized mentioned in consultations included: providing rewards and prizes for early adoption; developing public communication campaigns that feature early adopters; and continuing to publicize their successes.

Loss of agricultural land

Many producers and other stakeholders were concerned about the loss of agricultural lands to development and urban sprawl, particularly in Ontario and British Columbia. Many participants were concerned with who was buying agricultural lands and for what purpose. Increased calls were also made to better regulate foreign ownership of agricultural land, the purchasing of agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes, and the overall consolidation of agricultural lands in fewer hands across the country. Producers unable to afford their own piece of land have resorted to renting land which was identified as unstable and providing little incentive to adopt sustainable farming practices which tend to be long-term investments. Concerns around rising inequality between producers who can afford to own land and those who must lease were also shared.

3.2 What the SAS should aim to achieve

SAS vision and goals

While the draft vision statement (Annex A) provided in the SAS Discussion Document, adapted from the Guelph Statement of the Sustainable Canadian Agriculture Partnership, was supported by some participants, others expressed that it needed to be broadened beyond economics, should be more ambitious, and needs to look towards 2050. There was general support of the draft goals (Annex A) provided in the SAS Discussion Document, with more specific suggestions provided around wording and structure. Support for a goal on data and measurement was especially evident; specifically, the need to address data gaps related to the goals identified in the SAS across all priority areas. There was an underlying view from feedback that an economic lens needs to be applied to all the goals to communicate that environmental performance must work together with the financial resilience of farms. Specific wording suggestions will be taken under consideration when revising the SAS vision and goals.

Priority areas

Agri-environmental issues in Canada vary across the country, due to diversity in production systems, landscapes, and agroecosystems. The section below provides an overview of what was heard regarding the five priority issue areas of the SAS. While each issue area is unique, it is important to note that they were often discussed in connection with each other, reflecting each issue’s complexity and interconnectedness.

Climate change mitigation

Two divergent perspectives emerged from feedback related to the role of the agriculture sector in mitigating climate change. Some participants expressed that the SAS should aim for a net-zero agriculture sector to meet the urgency of mitigating climate change impacts, while others expressed that net-zero is not achievable in the agriculture sector and committing to that goal would set the sector up for failure. Others expressed that climate change mitigation should not overshadow the other priority areas. The most frequently mentioned approach to support producers in reducing emissions on their farms was to offer incentives for adopting new clean technologies and BMPs, and to reduce reliance on inputs. Several producers shared that they are interested in using clean energy sources on their farms but are limited by the high upfront capital costs to invest in equipment, identifying the need for partnerships with energy companies as one way in which to offset costs. The need to link data collection and analysis to decision making and policy to reduce emissions was also clearly highlighted.

Climate adaptation and resilience

In general, participants expressed that adaptation is an important goal of the SAS that should complement and align with Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy. Soil health and water were regularly raised in connection with adaptation and resilience, illustrating the importance of integrating environmental issues. Defining “resilience” and determining how to measure the resilience of the agriculture sector was noted as a particular challenge, and it was noted that adaptation is an ongoing issue and should not be treated as a “one-off” investment, but instead receive continuous funding. Examples of specific areas the SAS should focus on to support adaptation included agronomic practices (for example, converting marginal agricultural croplands to less intense uses and increasing the number of trees on agricultural lands); tools and technologies (for example, supporting investments in sustainable irrigation and undertaking climate science research to support innovative adaptive practices, products, tools, and technologies); promoting and breeding crops that are more resilient to climate change pressures (for example, heat, drought, pests, etc.); and including F/P/T government funding programs to incentivize practices that increase resilience on farms. Some producers shared successes with using different crop varieties. One example that was shared was growing winter wheat cultivars that are more climate resilient, more water-use efficient, and better at pest control to qualify for ecolabel certification through the “Habitat-Friendly Winter Wheat Eco Label Program” for diversified market access as well as providing more options for crop rotation, improved soil health, and expanded wildlife habitat.

Biodiversity

The majority of participants confirmed the importance of biodiversity as a priority area for the SAS and expressed that it should be given the same level of attention as climate change mitigation. However, some producers expressed that given all the other environmental priorities – especially regulations, reporting on GHG emissions and mitigation – biodiversity is a lower priority, and others did not see it as a concern on their farms. In general, participants expressed that the SAS should align with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Agriculture Sector Species at Risk Conservation Action Plan for improved coordination. Examples of specific areas where the SAS should focus in terms of biodiversity included direct supports to implement practices that protect and enhance biodiversity-rich features in agricultural landscapes (for example, wetlands, grasslands, habitat corridors), converting marginal land to natural areas, reducing nutrient runoff, implementing integrated pest management, diversifying crop rotations, and investing in research and data collection. While some producers shared the practices they are implementing on their farm that support biodiversity – such as shelterbelts and hedgerows – other producers noted more education on biodiversity is needed.

Water quality and quantity

Overall, we heard that the SAS should place importance on protecting both water quality and quantity in the agriculture sector. Examples of specific areas where the SAS should focus in relation to water quality included reducing nutrient and pesticide run-off in waterways, protecting wetlands, developing plant breeding innovations and the linkages between water quality and quantity and soil health. In relation to water quantity and concerns about future water availability, a suggested intervention was the development of irrigation strategies. This was of particular concern for Western Canada. Further feedback in this area of water management included the need for agricultural extension services and infrastructure support to manage water resources, and using watershed-based strategies to ensure a regional rather than provincial based approach to solutions. The need for research, training, and data collection activities such as water monitoring systems was highlighted as critical for confronting both water quality and quantity challenges.

Soil health

Through consultations, the definition of ‘soil health’ was an area of contention and participants noted that a clear definition of the term is needed. Some producers were surprised soil health was identified as an issue given that soil health has improved substantially in Canada, particularly in the Prairies. Others noted the absolute importance of improving soil health across Canada, especially in Eastern regions. Several suggestions were put forth to improve Canada’s current soil health, including adopting regenerative farming practices, increasing carbon sequestration, reducing chemical inputs by opting for organic alternatives, and increasing soil cover throughout the year. Some producers noted the importance of programs such as OFCAF which provides incentives to plant cover crops, resulting in reduced soil loss in ditches and waterways, increased soil fertility and reduced need for inputs. Developing a national soil health strategy – in partnership with producers – was repeatedly suggested to explore and research the best ways to manage soil health targets and explore the technological challenges of implementing new methods of measuring soil and developing advice to producers based on regionality. A national soil health strategy could promote positive practices, ensure access to effective measurement tools, increase knowledge transfer, and manage soil data.

Targets

Through the survey and submissions, participants provided a suite of specific proposals for targets for the SAS, including, for example, targets for total acreage under particular farming practices, land use and conservation, emission reductions including nitrous oxide and methane, nutrient efficiency targets, and carbon sequestration. A key theme that emerged was the desire to set achievable targets that would not threaten the productivity or profitability of farms. The importance of partnering with the sector to support producers in reaching those targets was raised, as meeting targets would be a function of affordability and accessibility of technologies. Some concern was expressed around the potential of identifying realistic targets when data gaps continue to be a key challenge, and using qualitative targets until enough data becomes available to set quantitative targets was a solution provided. Not all respondents were supportive of targets; some did not see the value of setting targets in the SAS.

3.3 Actions to advance sustainability in the sector

The section below highlights key themes that emerged from the consultation about what actions need to be taken to advance sustainability in the sector.

Direct incentives to increase the adoption of BMPs and technology

A clear theme heard during consultations was the need for direct financial support for producers to encourage the continued adoption of BMPs and technologies. Both direct incentives and financial support were highlighted as the preferred approach by producers prior to pursuing any additional regulations in the sector. They emphasized that incentives needed to be long-term and should consider the cost of adoption, return on investment, and the ecological goods and services provided. Furthermore, incentives and support must be made available to a variety of farm sizes particularly to those who do not have the capacity to measure GHG emissions or carbon sequestration, or are unable to afford costly clean technologies. We also heard that as there are such a wide variety of BMPs and technology that have environmental benefits on-farm, focused lists for producers on BMPs that would be best suited for their area or type of farming would be helpful.

Through the consultations, concerns were raised about existing programming, including confusion and overlap between P/T and federal-only environmental programming. With the number of programs available, producers and organizations are unclear which programs offer what benefits and what they are eligible for, making it difficult to navigate. Cost-shared programming can also be prohibitive for small scale producers and new entrants who do not have the capital to participate. Respondents highlighted that the design of the SAS must consider what is already being done and planned at the P/T level to avoid duplication with existing initiatives and must be coordinated across federal departments.

Other incentives to increase adoption of BMPs and technology

Participants noted that while direct incentives are crucial, other approaches could also be used to incentivize adoption of BMPs and clean technologies. Some ideas that were shared included:

- exploring how public and private actors can work together to support producers in adopting more complex and costly practices. This could include supporting financial institutions in providing non-traditional lending services and taking greater risks in supporting producers with new technologies and innovative initiatives.

- discounts on production insurance premiums incorporated into existing Business Risk Management (BRM) programs.

- funding or insurance programs that would allow producers to offset a yield decline that they may initially experience when adopting environmentally sustainable practices (for example, reduced tillage, cover cropping, and intercropping) could increase adoption rates and mitigate financial uncertainty.

- supporting initiatives that meet environmental goals through government guarantees for bank loans. Banks are reluctant to loan on emerging markets and technology that has not been proven in Canada. The government could support new initiatives by providing lines of credit, tax credits and rebates, grants, and low-interest loans to cover the costs of equipment and infrastructure upgrades.

- assistance and investments in on-farm research to producers that assist in long term financial resiliency of farms and the creation of programs that encourage producers to seek education in the agriculture sector would be helpful.

Market based approaches

Participants felt that Canada is behind globally in positioning its agricultural sector to be rewarded and recognized for climate action. The SAS was noted as an opportunity to provide new standards and stimulate new partnerships and collaborations to enable markets to recognize and reward environmentally sustainable choices along the agri-food supply chain. We heard that market-based approaches need to be accessible and easy to navigate for producers as complexities can limit participation. Government guidance and support could promote a better use of market-based approaches if, for example, a level-playing field is developed. The existing carbon offset market was met with mixed feelings throughout consultations. On the one hand, it was identified as an additional income stream for producers; on the other hand, it was viewed as something that required very complex data capture and it was not clear how this would translate to the agriculture sector. Insets, however, were viewed as an area with more potential as a leveraged market-based approach in the sector.

The benefit of assurance systems or certification systems was also shared. We heard that the sector would like to see more government recognition of sustainability standards developed by industry and that collaboration across certifications is also needed. For example, a common sustainability assurance label could be established to address consumers concerns and enhance understanding of assurance labels across certifications. A limitation raised included the lack of knowledge and tools required to measure outcomes or meet reporting requirements for assurance standards.

Knowledge transfer and extension

Ensuring that producers have the knowledge and information they need to adopt practices and technologies on their farm was a key theme noted by both producers and other participants. This was expressed particularly in terms of having on-the-ground support of agrologists to share their knowledge and expertise in adapting specific practices to their farm. Producers expressed a desire for unbiased information through government, or trusted producer associations to filter through the large amounts of options and information available to them to better know what would work on their own farms. They expressed a need to have more data shared with them and an interest in applied research and demonstration of practices through living labs, demonstration farms, online workshops, communities of practice, and the availability of publicly accessible online databases with information on sustainable practices. Agronomic support through extension should also be long-term, reliable, and dependable and based on local and specialized commodity knowledge. In supporting the principle of Reconciliation, specific reference was made to the capacity barriers for agricultural production on reserve lands and the need to provide culturally appropriate extension services.

Peer-to-peer producer networks were also identified by producers and other stakeholders as important for sharing experiences, knowledge, and information, and strengthening producer relationships, especially for new and young producers. These peer-to-peer networks could be a way to promote mentorship and acknowledge the successes of early adopters so they should be supported by the government. We heard several examples of peer-to-peer networks already established, including Farmers for Climate Solutions peer-to-peer training programs, agri-environmental clubs in New Brunswick, club conseils in Quebec, and events like canolaPALOOZA days across the Prairies.

Connections across the supply chain

While the SAS is currently focusing on the agricultural production level, the importance of influences further along the supply chain, including manufacturers, processors, retailers and consumers, was raised by participants as having a large impact on the demand for farm products and ultimately what is to be planted or raised and how. Participants expressed that the onus of developing a sustainable agricultural sector should not solely be on the shoulders of producers; every player in the value chain has a role to play in the development of a sustainable sector. Instead, the opportunities of leveraging a value chain approach were raised as a way to create an enabling environment for producers and others in the value chain to take on sustainable practices and technologies. Input manufacturers, processors, retailers, and consumers have different influences over agriculture, can shift the demand of agricultural products and the way they are produced, and share in the potential financial risks and compliance burdens with producers. Consumers were identified by several stakeholders as an important group with which to build trust and engage through public awareness and education outreach.

Research and technology

Research was a recurring topic throughout consultations. There was strong support for more resources available for public research in AAFC and in partnership with academia and applied research associations, with many participants noting the decrease in AAFC-led research and funding in recent decades. Some of the most frequently identified topics for research included:

- public breeding programs that are regionally specific.

- genetics and variety development for climate adaptation that consider biotic (pest, disease) and abiotic (heat, drought) characteristics, while supporting high yield and product quality.

- research to decrease input use (especially fossil fuel-based inputs) and increase nutrient use efficiencies through practices or circular flows of nutrients on farm.

- the economics of sustainable production which could shed light on the business case for sustainability for producers and give them a clearer understanding of costs and returns on investment when adopting environmentally conscious practices or technologies on-farm.

Producers favoured regional and more localized participatory research, as well as making research results more accessible in approachable language for producers. AAFC’s Living Labs were identified as good models for producer-led research that has been useful in helping producers work through challenges on their farms.

There was an overall appreciation for the value of traditional knowledge and the need for ensuring this is considered with scientific evidence and not displaced by it.

Technology and innovation were also topics with high interest which were frequently blended with research and development. A common perspective was that a flexible regulatory environment is required to de-risk the process of innovation as well as provide opportunities for producers to adopt and test new technologies on-farm. Infrastructure, including broadband connectivity, was identified as a key barrier for the adoption of technologies, especially precision and digital technologies on-farm. Farmer-led innovations and Canadian-led partnerships were encouraged. Several suggestions for specific technologies were named throughout consultations, some of which included bioeconomy technologies such as biodigesters and methane capture systems, as well a general call for more clean technologies on-farm to promote energy efficiency and reduce GHG emissions.

Regulatory approaches

It was clear throughout the consultations that direct incentives were favoured over regulatory approaches to incentivize the adoption of BMPs. Producers were concerned that more regulation would present them with increased administrative and financial burdens, and, in some cases, threaten the viability of their farm. Nonetheless, some regulations were seen as more favourable than others. For example, regulations preventing wetlands conversion to agricultural lands; protecting prime agricultural from urban sprawl; controlling water pollution, and developing a clear regulatory framework for the carbon market, were seen as acceptable areas to explore regulatory approaches by some participants, including some producers. Provinces and territories play an important role when it comes to regulatory incentives, given that regulations relating to land use are under the jurisdiction of provinces and territories.

As opposed to imposing new regulations, participants encouraged the federal government to harmonize existing regulations with other federal departments and the P/Ts to minimize confusion and increase the effectiveness of their regulations. The need for regulations to be nimble and flexible was expressed several times in the name of innovation and sustainability, providing examples of approving animal feed and biological inputs which have already been approved by Canada’s trading partners. While the feedback largely focused on the need for streamlining regulations and reducing red tape for innovation, certain regulations were identified as discouraging producers from sustainable activities on their farms in some cases.

Lastly, leveraging BRM programming to incentivize the adoption of BMPs was identified as an effective method to streamline regulations. For example, producers adopting practices that make their farm operation more resilient could be rewarded through BRM by receiving lower risk premiums and crop insurance. Few stakeholders were opposed to this, though some stated that BRM programming is already too complex to take on additional layers of compliance and should remain production risk management tools only. Others noted that BRM and crop insurance should first be modified to be more accessible to multiple commodities and farm sizes.

Broader and longer-term approaches

In terms of broader changes needed in the sector, some participants noted that Canada’s agricultural production should not be dependent on fossil fuels, citing both on-farm fuel use and inputs. It was noted that decoupling fossil fuels from inputs could help producers decrease their dependence on uncertain global oil prices affecting their costs of production. Circularity was also brought up to use resources from other farms, sectors, or even cities to decrease waste and recycle nutrients for use as on-farm inputs.

Supporting local and regional food systems to decrease the distance between producers and consumers, develop rural communities and enhance local food security was also identified throughout consultations by producers and various stakeholders. One success story shared from Prince Edward Island (PEI) involves a group of vegetable producers growing diverse vegetables with agri-environmental practices coming together with the help of the Prince Edward Island Certified Organic Producers Cooperative to develop PEI’s first cooperative food hub, the “Growers Station.” Producers cooperatively supply fresh produce to local restaurants and wholesalers, with the aim of extending this to the consumers in the near future. This has helped reduce transportation and storage costs, while also decreasing their GHG emissions. There were also several submissions discussing the need to push for plant-based diets to align with recommendations from Canada’s Food Guide to decrease GHG emissions, land use issues, and ethical concerns in livestock production. Some submissions, which included producers, noted a disconnect between the Government of Canada’s simultaneous push for sustainability and promotion of economic growth and exports in the sector.

Lastly, a very popular comment seen across several consultation groups and from both producers and stakeholders was the idea to use systems thinking in policymaking, looking at all the elements of the food system (for example, processing, retailing, consumption, etc.), while including the social, economic, and health contexts and relationships with agricultural production. Similarly, “whole-of-government" approaches were also recommended, where AAFC would work with various federal departments and jurisdictions to take on a “systems approach” to agri-environmental policymaking.

Indigenous food systems

Stable access to agricultural lands to continue producing food while also passing down knowledge to promote food security was considered crucial to participants in the Manitoba Métis Federation-led consultations. Many Red River Métis who hold valuable knowledge in modern and traditional food production are aging, meaning a loss of agricultural knowledge. Participants shared that while environmentally beneficial initiatives were of strong interest to Red River Métis producers, these initiatives can be quite costly. Furthermore, small and medium scale producers supporting local food systems require additional support as they often do not have enough resources to connect with markets, often competing with larger operations with more resources. More incentives and opportunities are also needed to encourage the next generation to engage in food production, including the promotion of knowledge sharing.

Water, soil conservation, and a “food as medicine” approach were emphasized, with specific recommendations promoting agroforestry, silviculture, and silvopasture on agricultural lands. There was also an interest in integrating alternative energy production with agriculture and developing ways to better adapt to climate change. Participants noted that the SAS should look to reflect the values of the Red River Métis and other Indigenous Nations to use as guides for policy and programming.

In smaller focus group sessions with First Nations producers, climate change was identified as impacting First Nation and Indigenous operators in a number of ways including declining production and as a result, farm revenue, increased operating costs, unpredictable weather patterns threatening water and soil conditions, and increased loss of native plants and wildlife crucial for cultural activities. Water quality and quantity was identified as an issue by First Nations participants in the sessions, which has limited agricultural expansion, and undermined community food security and food sovereignty goals.

Several recommendations were put forth during focus group sessions, including ensuring First Nations producers have equal access to programming and funding, low or zero-interest loans to develop infrastructure, especially relating to water processing and filtration, and food storage facilities. The need to promote natural land management was also identified through using permaculture practices, safeguarding native plants, and reusing waste. First Nations participants indicated that many First Nation producers are small to medium scale operations, favouring organic and natural processes that do not use conventional agricultural inputs.

Recommendations for the SAS centred on using practices that reduce dependency on synthetic inputs in farming and promoting environmental feeding practices such as feeding livestock with food waste and grass. Climate change adaptation was an important theme in First Nations focus groups where resilience mechanisms were more firmly entrenched in Western Provinces than in the Maritimes provinces. In trying to address increasing vulnerabilities associated with changing weather patterns, First Nations producers in the Maritimes noted that emergency management and water planning were necessary to help deter fires and floods that damage agricultural operations. There was also interest in research on plant varieties that can withstand changing climates.

Common to all Indigenous producers consulted was a concern with attracting the next generation to farming and identified the need for succession planning support. Education and training in agricultural production (including landscape management, permaculture techniques, and forest and fire management), and food processing and cooking were identified as important to develop among communities. Finally, participants noted the need to include Red River Métis and First Nations in the decision-making and design of agricultural policy and programming.

Stakeholders and members of the public who submitted survey responses and written submissions, or participated in workshops, noted the need to meaningfully represent Indigenous communities in the SAS and promote Indigenous knowledge in agricultural production as important for sustainability. Some participants suggested that existing programs be refined to better serve Indigenous producers, the need to collaborate with Indigenous groups in Indigenous-led research and to commit to Reconciliation and self-determination, especially as they relate to environmental justice and actions impacting Indigenous communities, their lands, territories, and resources.

3.4 Data and measurement

Measuring agricultural emissions accurately is a complex task and it was raised throughout consultations that there is a lack of consistency across data collection and analysis at the national, regional and field levels, and that there are distinct concerns at each level.

National data

Various concerns were identified about how agriculture is modelled in the National Inventory Report (NIR), which represents Canada’s official accounting of GHG emissions as reported to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Concerns raised included how adoption of new or additional on-farm practices are considered in the NIR modeling and that it is challenging to capture specific practices. It is difficult to understand the full agricultural GHG emission picture since carbon sequestration from trees on agricultural lands and land conversion are considered separate from the agricultural sector in the NIR. We also heard from other stakeholders along the supply chain wanting a clearer picture of emissions throughout the food system to determine how they can make smart environmental decisions in terms of sustainable sourcing, understanding their scope 1 (direct), scope 2 (indirect), and 3 (upstream) emissions, and having a clearer picture and story to tell consumers.

Regional data

Participants noted that looking at groups of producers geographically or by commodity would help develop trends and better understand the regional needs, challenges, and opportunities across the country through data aggregation. This would also help identify gaps in particular datasets, in terms of regions, commodities, soil, water, biodiversity or other data contributing to a clearer understanding of GHG emissions and other impacts on the environment. Currently, data is fragmented and drawn from multiple sources, making it challenging to create comprehensive datasets that are valid, particularly in regions without historical data. It was noted that methodology will need to be standardized in terms of sampling, collection, measurement, and indicators.

Field data

Participants acknowledged that challenges in collecting data exist due to the variability of farms and on-farm practices, the high cost and complexity of data collection, and concerns over privacy and ownership of farm-level data. Gathering complete and timely data is crucial to understanding the effectiveness of programs and policies in the agriculture sector and informing decision-making. However, producers have identified their lack of time and capacity to take on more activities such as data collection which can be time-consuming and complex. Several producers noted the need to develop measurement tools that are accessible and user-friendly with the ability to give a “whole of farm” perspective. These tools would provide producers the ability to measure and collect data on their farms to have a better idea of environmental benchmarks on their farm, potentially helping them make production decisions and more informed investments.

Ultimately, producers will only collect data if they see its value and have developed trust with those collecting and using the data. Integrating economic data with agri-environmental data was shared as important for producers to provide a fuller picture of how these practices are affecting their farm and their bottom lines. For example, compensating producers for data sharing that will be used for a “public good” such as GHG emissions or biodiversity, could incentivize data collection.

Data governance

A strong call for a data strategy to collect, manage, and communicate data on GHG emissions, biodiversity, water, soil health and resilience was a common theme during consultations, developed in collaboration across governments, industry groups, and producers. Participants shared that solutions to address data and measurement challenges must be developed with the sector and various stakeholders at different levels to measure change. Producer-friendly data tools would be needed to identify sustainability successes and areas of improvement of the farm.

Participants also identified examples of various public and private data initiatives at the regional level, and suggested that these be identified and built upon as we move toward a data strategy including:

- AG Transparent (US)

- Australia Agri-Food Data Exchange (Australia)

- Canadian Roundtable for Sustainable Crops Metrics Platform

- National Index on Agri-Food Performance (Canada, in development)

- Dairy Sustainability Framework

- eGrape (Ontario Grape Growers)

Finally, the importance of data governance was raised by industry to ensure clear and commonly agreed sets of definitions, baselines and targets are being used. A data governance strategy would enable the SAS to identify gaps and explore effective approaches to filling those gaps in the future.

4. Next Steps

The extensive consultations have resulted in valuable insights and suggestions that will inform the development of the first Sustainable Agriculture Strategy for Canada. Continued collaboration and engagement across governments, industry, producers, non-governmental organizations, Indigenous partners, and academics will be critical for the successful development and implementation of the SAS, to achieve shared environment and climate goals. This engagement will support the development of the SAS and the Strategy is expected to be released in 2024.

Annex A: Original SAS Vision and Goals from SAS Discussion Document

Proposed Vision for a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy

Canada is recognized as a world leader in sustainable agriculture and agri-food production and drives forward from a solid foundation of regional strengths and diversity in order to rise to the climate change challenge, to expand new markets and trade while meeting the expectations of consumers, and to feed Canadians and a growing global population.

Proposed Goals for a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy

- The agriculture sector is resilient to short and long-term climate impacts while growing productive capacity, and has adapted to changing contexts due to climate change.

- Environmental performance is improved in Canada's agriculture sector, contributing to the environmental, economic, and social benefit of all Canadians.

- The agriculture sector plays an important role in contributing to Canada's national 2030 GHG emission reduction and net-zero by 2050 targets while remaining competitive and supporting farmers.

- A more comprehensive and integrated approach is taken in addressing agri-environmental issues in the agriculture sector, across policy, programming, and partners in the value chain.

- Canada has addressed data gaps and improved capacity to measure, report on, and track the environmental performance of the agriculture and agri-food sector.