Table of contents

- Summary

- Ammonia emissions in Canada: why do they matter?

- What causes ammonia emissions?

- The Ammonia Emissions from Agriculture Indicator

- Ammonia emissions in Canada – current state and the change over time

- How can ammonia emissions be reduced?

Summary

- Nitrogen is a critical nutrient for plant growth but loss of nitrogen via ammonia emissions can have important environmental and economic consequences.

- In Canada, agriculture is responsible for about 93% of human-caused ammonia emissions to the atmosphere.

- The Ammonia Emission from Agriculture Indicator estimates ammonia emissions from agricultural activities. It also measures whether this is changing over time.

- Canada’s ammonia emissions have increased over time, mainly because of increased use of fertilizers. This is because of an increase in annual crops, increased fertilizer application rates and fewer livestock.

- Beneficial Management Practices to reduce ammonia emissions include not overapplying fertilizer and changing livestock feeding, grazing and housing methods.

Ammonia emissions in Canada: why do they matter?

Nitrogen is a critical nutrient for plant growth. Nitrogen in soil can be lost to the atmosphere in the form of ammonia emissions. In Canada, agriculture is responsible for about 93% of human-caused ammonia emissions to the atmosphere. This loss of ammonia has important environmental and economic impacts.

At high concentrations in enclosed spaces (such as poultry barns), ammonia can be an irritant, or even toxic, to humans and animals. When ammonia reacts with gases in the atmosphere, particulate matter can be produced. Particulate matter can be harmful to human health. Because of this, ammonia is considered to be a Criteria Air Contaminant in Canada. Particulate matter can also be harmful to natural ecosystems. It can be transported by air currents for hundreds of kilometers and deposited in vulnerable, natural areas such as alpine vegetation, oligotrophic peat bogs, calcium depleted soils and pristine lakes. Particulate matter can also contribute to smog and reduce visibility, leading to negative impacts on economic activities such as tourism. Ammonia can also break down into nitrous oxide which is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.

The loss of ammonia into the atmosphere also has economic impacts. About 11% of nitrogen fertilizer used in Canada is lost to the atmosphere as ammonia. This results in a loss to producers of about 400-800 million dollars annually.

The Government of Canada has committed to annually report on ammonia emissions from agricultural and non-agricultural sources. This helps inform Canadians about the contribution that agricultural activities make to the national ammonia emissions, and could be used to provide information about management practices that reduce environmental impact.

What causes ammonia emissions?

Ammonia emissions are caused by all plant and animal life when proteins are digested and break down. These emissions occur in natural and managed landscapes.

In agricultural systems, ammonia comes from livestock manure and from nitrogen fertilizers. In livestock, nitrogen is excreted in the form of urea (from mammal urine) and uric acid (from bird manure) as well as other complex molecules in faeces. Ammonia is released when these compounds break down. Ammonia emissions also come from nitrogen fertilizers containing ammonia, ammonium or urea. As a result, the highest ammonia emissions occur in regions with concentrated livestock production.

Ammonia emissions differ across seasons and time of day. Most ammonia emissions occur in spring. This occurs because of increased temperatures (which affect atmospheric chemistry and transport), farming activity (manure spreading and fertilizer application) and animal activity (such as calving). Little ammonia is emitted in winter because there is little spreading, but also because of low emissions from relatively-cold manure storages and animal housing. Ammonia emissions vary throughout the day because of changes in light, temperature and overall farm activity.

The Ammonia Emissions from Agriculture Indicator

The Ammonia Emissions from Agriculture indicator measures ammonia emissions on agricultural lands from livestock production and fertilizer applications. It also measures whether this is changing over time. The indicator uses information about agricultural production, management practices and emission factors associated with agricultural practices. It is calculated from many sources of information:

- management practices from farm surveys and expert opinion, and ammonia emissions from scientific research

- animal numbers from the Census of Agriculture

- fertilizer consumption from the fertilizer industry

- crop areas from Statistics Canada surveys

Ammonia emissions are reported in five classes: Very Low, Low, Moderate, High and Very High.

The Ammonia Emissions from Agriculture Indicator is calculated annually. It helps Canadians understand how emissions from crops and livestock are changing over time, and can assist in identifying farming practices that can reduce environmental impact.

Ammonia emissions in Canada – current state and the change over time

In 2021, 39% of emissions were from fertilizers and 30% of emissions were from the beef sector. Ammonia emissions across all livestock sectors were linked to housing (including feedlots) plus grazing (55%), land application of manure (37%) and manure storage systems (8%).

Although fertilizer application rates and ammonia emissions vary by region and by crop type, high concentrations of emissions were mainly from livestock. Concentrations were greatest in the Lake Ontario to St. Lawrence River corridor in Ontario and Quebec (pigs and dairy), in the Lower Fraser Valley in British Columbia (dairy and poultry), southern Alberta (beef feedlots) and southeastern Manitoba (pigs). High concentrations in the Atlantic provinces are associated with limited amounts of agricultural land associated with livestock. Although these high concentration areas only impacts a small number of regions, these areas are often located near large urban centers, increasing the potential for impact on the human population. Saskatchewan had the lowest, overall, emissions concentrations. This is because of thinly distributed fertilizers and low-density cow-calf operations.

Emissions from livestock production and from fertilizer use across Canada are highest in May. This is because of manure and fertilizer applications prior to planting. They are lowest in winter, when manure is in storage and the temperatures in storage facilities, and in most cattle housing, are relatively low. Greatest exposure risk, overall, is associated with May ammonia emissions in the Lake Ontario to St Lawrence corridor, the Lower Fraser Valley of British Columbia and Winnipeg.

Total ammonia emissions from livestock production and nitrogen fertilizer application in Canada, 2021

Ammonia emissions increased from about 325 kt to 403 kt between 1981 and 2021. The percentage of emissions caused by livestock decreased from 83% to 61% between 1981 and 2021. Much of this change was caused by a decline in the beef cattle population because of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE). The largest declines occurred in the Prairies (especially Alberta) where the beef industry is most concentrated. Other factors contributed to the decline include: a loss of about 2 million swine; and gradual decline in dairy numbers because of increasing milk production per cow (mostly impacting emissions in Manitoba and eastern Canada).

Change in total ammonia emissions per hectare, 1981 to 2021

During this same period, the percentage of emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use steadily increased. This was caused, mainly, by an increase in arable crops (replacing summerfallow and perennial forages), increased fertilizer rates (because of more canola) and fewer livestock.

The percentage of farmland in each of the five emission classes changed markedly from 1981 to 2021. On the Prairies, the amount of land in the lowest emission class declined from an average of 70% in 1981 to 43% in 2021. Over this time, In Ontario and Quebec, the amount of land in the highest emission class declined by 14%. Generally, emissions declined in the Mixedwood Plains Region of central Canada because of fewer dairy and beef cattle. On the other hand, emissions increased on the Prairies because of an increase in pigs, beef cattle and fertilizer.

How can ammonia emissions be reduced?

Many farmers are already using Beneficial Management Practices (BMPs) to reduce ammonia emissions. These include:

- staged (or phased) feeding of protein to pigs and chickens

- use of low-emission application of liquid manure (especially injection of liquid pig manure) into cropland

- increased winter feeding of cattle on pastureland rather than in wintering feedlots

Efficiencies in other farm activities have reduced ammonia emissions such as higher milk production per cow (reducing overall herd size) and increased feed efficiency and growth rates in meat (broiler) chickens (reducing time needed for animals to reach market weight).

Because there are many sources of ammonia emissions associated with livestock operations, reducing emissions is challenging. However, low-cost BMPs could reduce livestock emissions by up to 26%. These include:

- stabilizing applied manure or fertilizer using acidification or inhibitors

- increasing grazing of cattle (as opposed to using confined feeding)

- avoiding oversupply of feed protein by closely matching the amount of fed protein to animal requirements

- using low-emission manure and fertilizer application methods such as surface banding, injection or rapid incorporation

- reducing losses from animal housing by: adding chemicals to bedding (such as alum and sulphuric acid); immediately segregating slurry feces from urine; using floating covers for in-barn slurry tanks; or using absorbent filters on barn vents

- reducing summer emissions that may expose people enjoying the outdoors by curtailing field spreading and by acidifying barn floors

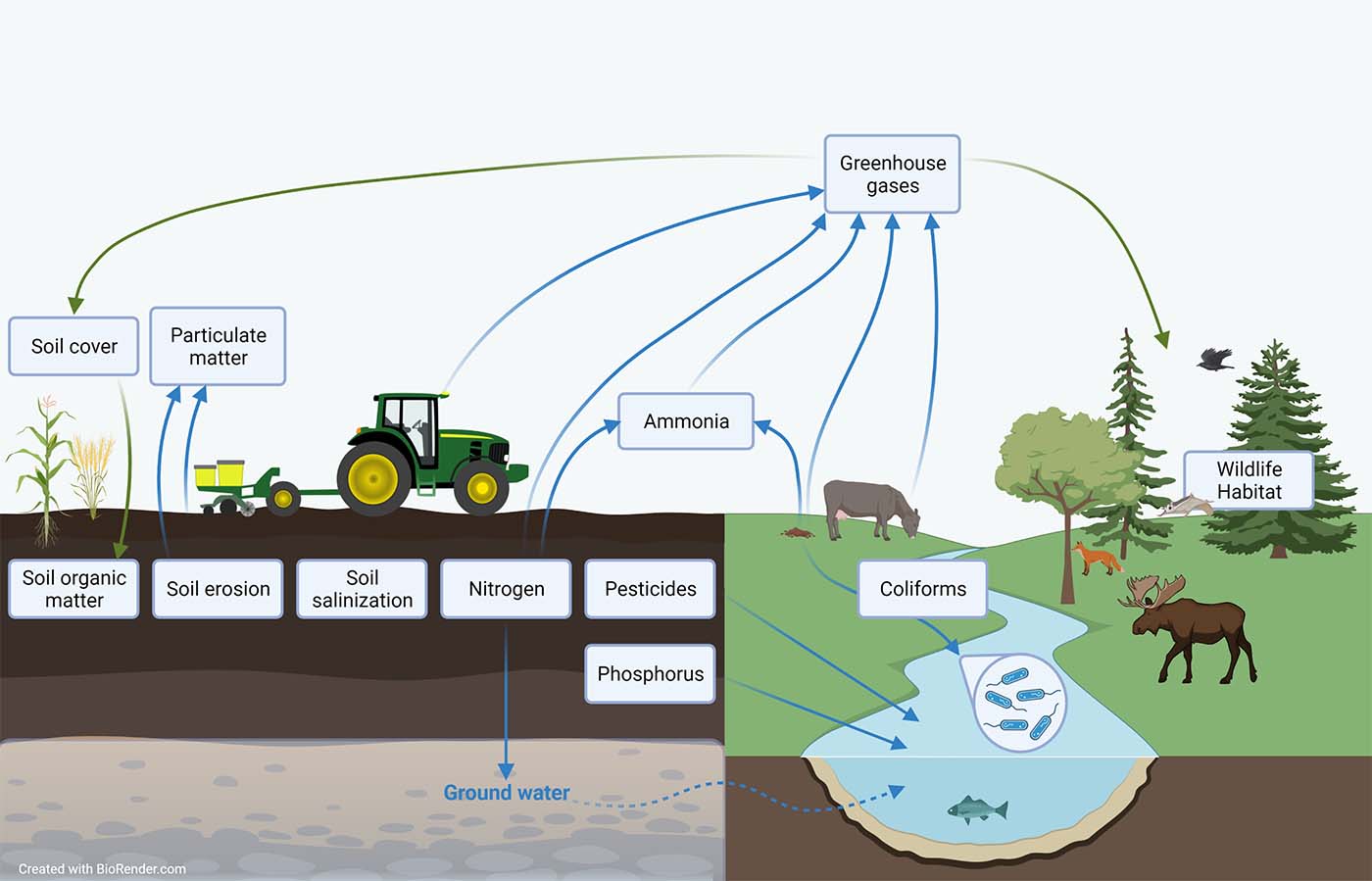

Description of the image above

An infographic showing an agricultural landscape with crops, a tractor, soil and grazing livestock adjacent to a natural landscape with a watercourse, forest and wild animals. Info boxes are placed to show to which element of the landscape each agricultural sustainability indicator pertains. Arrows connect some of the info boxes to show interrelationships. One info box is present for each of the following indicators: Soil cover, particulate matter, soil organic matter, soil erosion, soil salinization, nitrogen, pesticides, phosphorus, ammonia, greenhouse gases, coliforms and wildlife habitat.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's agri-environmental indicators (AEIs) provide a science-based snapshot of the current state and trend of Canada’s agri-environmental performance in terms of soil quality (soil organic matter, soil erosion, soil salinization), water quality (nitrogen, pesticides, phosphorus, coliforms), air quality (particulate matter, ammonia, greenhouse gas emissions) and farmland management (agricultural land use, soil cover, wildlife habitat). While indicator results are presented individually, agro-ecosystems are complex, so many of the indicators are interrelated. This means that changes in one indicator may be associated with changes in other indicators as well.

Related indicators

- The Particulate Matter Indicator estimates the contribution of primary particulate matter from agriculture into the atmosphere.

- The Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Indicator tracks the greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide) associated with Canadian agricultural activities.

- The Nitrogen Indicator estimates how efficiently nitrogen is used by crops and the amount of surplus nitrogen in agricultural soils.

Additional sources and downloads

- Discover and download geospatial data related to this and other indicators.