Why a sector-specific strategy for agriculture?

Agriculture and agri-food sector faces notable obstacles:

- Highly varied: 200,000 farms spread across various commodities and 8,000 food and beverage processing businesses

- Rural location (particularly primary ag)

- Seasonality dictated by environment

- Older-than-average workforce

- Just-in-time supply chains

- Public misperceptions

Shortages meaningfully impact the sector’s potential and result in lost economic capacity:

- Estimated annual lost revenues due to labour and skills shortages:

- Limit economic growth by preventing or delaying expansion plans

- Workers putting in longer hours and burning out

These obstacles result in:

- Effects on food supply:

- Food loss (for example, crops left in ground, surplus animal destruction)

- Reduced consumer choice (fewer product lines)

- Lower output/inability to add value

- Risks to worker health and safety (longer shifts, productivity pressures)

- Heavy reliance on international labour

High vacancy rates persist despite constant domestic recruitment/innovative approaches

- Staffing bonuses, wage increases, and other incentives have not been effective enough

- Temporary foreign workers (TFW) will remain part of the solution, likely until automation is accessible

Shortage of labour will impact rural vitality

- In 2020, Canada’s agriculture and agri-food system provided 1/9 jobs in Canada, employing 2.1 million – largely in rural areas

- If labour shortages persist, existing workforce will degrade and companies lose opportunities

Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector faces a widening labour gap, severely limiting economic growth potential

Domestic labour gap

(does not include positions filled by TFWs)

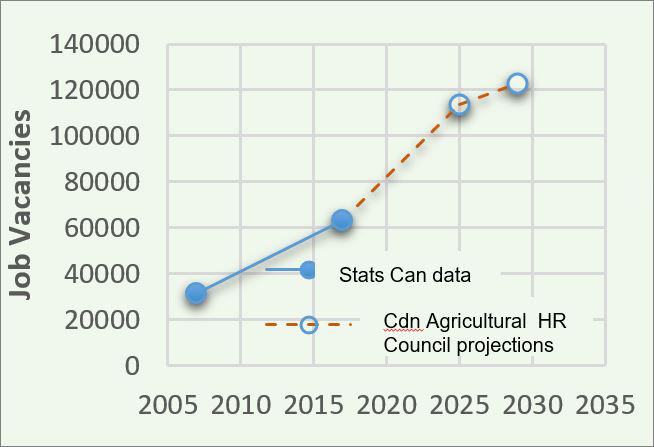

Description of the above image

- The Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council reports that the domestic labour gap in agriculture was just over 30,000 positions in 2007, and just over 60,000 positions in 2017

- They project that this gap will rise to nearly 120,000 workers by 2025, and to greater than 120,000 workers by 2029

- The domestic labour gap does not account for positions filled by temporary foreign workers

- Without concerted effort, the labour gap will continue to widen, increasingly leading to production challenges that weaken domestic and global supply chains and lost opportunities

- Not just on-farm labour – shortages in high-skilled roles hinder growth (for example, ag engineers) and affect thing like animal and plant health (for example, large animal vets, agronomists) and supply chain efficiency and resilience (for example, block chain developers)

Canada cannot contribute to global food security in times of uncertainty without a skilled and reliable agricultural workforce.

To tackle these issues, need cooperation across areas of influence, while acknowledging realities of the sector

- Systemic realities of the broader economy (for example, market conditions) and agriculture (for example, aging demographics, geographic isolation) will continue to have a significant impact on labour needs

- Federally, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) leads on labour and Temporary Foreign Worker Program reform and new housing standards, however there are other mandates to leverage in exploring innovative ways to attract and retain a variety of skills and labour – tax policy, rural infrastructure, innovation

- AAFC and provincial/territorial ministries of agriculture work with stakeholders, but mandate for labour typically resides in other ministries (for example, Labour, Education, Social Services) and is also impacted by municipal approaches

- Big role for industry to drive change in this space and Canadian Agricultural Human Resources Council (CAHRC) taking leadership role with Future Skills Centre-funded National Workforce Strategy for Agriculture and Food and Beverage Manufacturing

Balance immediate and future needs to drive change

Action Plan:

- Explore solutions:

- Automation and technology identification and development

- Targeted skills development and training

- Employment incentives

- Create conditions for industry to meet workforce needs (for example, childcare)

- Improve access to housing and reliable transportation in rural areas

- Keeping workers in the sector longer (for example, tax credits)

- Short-term:

- Continue promotion and recruit efforts

- Continue TFW program reform

- Expand pathways to PR for ag TFWs

- Consider data needs

- Long-term:

- Support automation and technology adoption

- Increase efficiency through adequately skilled workforce

- Stabilize labour sources

- Adequate data to track progress and inform decision-making

The aim is a skilled and reliable agriculture and agri-food workforce and a stable supply chain.

How do we get there?

Phase 1

- Budget 2022 - important step forward in implementation of TFW program reforms: the AgLS will complement these efforts and pursue options for longer term solutions

- Ensure coordination with existing efforts by ESDC, CAHRC (National Workforce Strategy), PTs, and others

- Explore unconventional solutions

- Stakeholder consultations

Phase 2

- Conclude consultations and share findings

- Develop solutions and Strategy elements: Fall 2022

- Official Launch of Strategy: Early 2023

- Implementation followed by ongoing policy and program work