This manual is meant to be an explanatory guide in which we have attempted to simplify the terms of the Animal Pedigree Act for easy reference. The manual contains comments on certain provisions of the Act and reflects the interpretation and policy of the Office of the Animal Registration Officer, which may change from time to time to reflect new legislation, jurisprudence or industry factors. In the case of any conflict between this manual and the Animal Pedigree Act, the latter is to be followed. This manual is not meant to substitute for independent legal advice and opinion.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Definitions and interpretations

The Animal Pedigree Act is a federal statute which establishes the broad legal framework under which breed associations (animal pedigree associations) may be established. Breed associations are corporate entities which derive their legal authority from the Animal Pedigree Act. Breed associations are established with respect to distinct and/or evolving breeds.

The Act contains an interpretation section which should be used to understand terminology in the Act itself (see also Glossary of Terms, chapter 8 of this manual). However, acts also need to be interpreted in their entirety. Likewise, by-laws and procedures need definition and interpretation. How do we arrive at definitions? Definitions may be derived initially from the Act itself but usually are fleshed out through experience and with input from many sources. Definitions are important because they help establish standards and limits by which activities may be measured.

In general, statutory provisions are given their ordinary meaning where possible. For breed associations seeking to clarify interpretations and define terminology there are numerous sources of information. The following categories are not intended to be exhaustive. They are sources of information which are in addition to the Act itself and may help with its interpretation.

Regulations

Many acts of parliament are clarified through enactment of regulations. Currently, the Animal Pedigree Act has no regulations which help define terms. The only regulation which currently applies to the Act is one which details procedures for winding down breed associations. Other acts and regulations, such as the Interpretation Act or the Health of Animals Act and its regulations, may be relevant in certain cases.

Legislative intent

Legislation does not generally seek to specify every detail but rather is intended by the legislators to embody certain purposes, priorities and limits. The purposes of the Act (section 3) and the role of associations (section 4) establish the overall intent. However, at times it may be difficult to discern the intent of specific provisions. In addition, legislation cannot anticipate every eventuality relating to activities carried out under its authority. There may even be inconsistencies, vagueness or gaps which are not recognized until later. The legislative process involves interaction of many people including extensive consultation with industry groups. Therefore, interpretation is often aided by understanding the historical context in which the legislation was developed.

Common administrative practices

The Animal Pedigree Act is administered by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the office of the Animal Registration Officer. In the course of administration, recommendations are made to the Minister, or other delegated authority, primarily for the purpose of approving amendments to by-laws. The Department exercises a limited supervisory role over associations but is available to serve in an advisory capacity. Administrators of the Act also interact with and advise others including bodies developing government policy and legislation, administrators of other federal statutes, related international bodies and non-governmental organisations. Every effort is made to ensure consistency not only among breed associations, but elsewhere as well.

Common industry practice and usage

Common practice usually develops through experience and common sense. Common practices change over time though, often enhanced by technological developments and scientific understanding. To facilitate understanding of special terms and new technology, the opening sections of the by-laws and/or policy and procedures manual may be organized to include definition of terms which will be used throughout the document. Special attention must also be given to changes in international practices which may affect trade in breeding stock.

Democratic processes

The Animal Pedigree Act requires that breed associations specify certain procedures in their by-laws regarding democratic processes. The by-laws should also be written in plain language and be accessible to all members. In addition to establishing rules in the by-laws, there are other important means by which associations can guarantee that the will of the majority is carried out while still hearing and respecting the minority. Guidelines on rules of order are available for reference to assist in ensuring a democratic process is followed. Federal and provincial departments also publish guidelines which can be useful to assist in the administrative process. Every association should specify what guidelines shall be used when their own by-laws, rules and procedures are silent on matters relating to the democratic process. A well-defined democratic process should help breed associations avoid almost all recourse to the judicial system. [see Chapter 3 - The Democratic Process]

Legal opinion

Administrators of federal statutes are aided by the federal Department of Justice from which legal opinion is obtained for internal use. However, individual breed associations may from time to time need to seek their own legal counsel. Legal opinion is generally bounded by the accepted system of laws in Canada and the provinces, by interpretation of statutes relating to a particular issue, by provisions of the Canadian constitution including the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and by legal precedent. Breed associations should be cautious about trying to be their own lawyers where contentious issues are involved.

Court judgement

Legal opinion is learned opinion, not law. If an issue can not be resolved by the parties involved it may eventually end up in a court of law. This is generally an expensive process. However, court judgements must be honoured and can sometimes help elucidate what is permitted or not under the Animal Pedigree Act and the by-laws of an association.

Finally, interpretation may be aided by use of dictionaries, scientific writings, policy directives or guidelines, etc .

Explanation of terms for breed associations

By-laws, policy and procedures can not be developed in isolation. In fact, given the changing nature of the business it is usually necessary to amend the by-laws regularly and do a complete review of the by-laws every five to ten years. Following are a few explanations of terminology which may help breed associations develop consistent definitions. These are guidelines only.

Breed standard

This term is used in several ways, and none all too consistently.

- in breed registries - breed standards are the essential trademark characteristics of a breed such as colour and coat pattern, horns,size, conformation, etc . Additional breed standards may include performance characteristics such as growth rate or milk production. These may be incorporated into the rules of ligibility for registration.

- in judging - breed standards have been used as equivalent to a 'standard of perfection' , 'true type' or 'ideal' for the breed.

- in extension and field use - breed standards are expressed in terms of the average and range of characteristics that can be expected.

(Distinct) breed

A breed is a population of animals with a common history and origin. There is not a standard definition to which everyone would agree. However, two important characteristics are that they must have unique distinguishing characteristics and be genetically stable from generation to generation.

Evolving breed

This is a population of animals which is not yet genetically stable. To be recognized under the Act an evolving breed should have a defined parental population, established breed standards towards which selection will be directed, and a breeding plan to get there.

Grading-up

Refers to the process of consecutively breeding animals towards a purebred status. Animals which are registered as purebreds are mated to animals of other breeds or of crossbred or uncertain genetic origin (grade animals). A first mating gives 50%, second mating 75% and so on.

Parentage verification

Refers to laboratory tests by which animals are compared to their parents. Tests determine if an animal can be included or excluded as a possible parent. An animal's parentage can never be confirmed 100%, but individuals can be excluded as possible parents with a very high degree of accuracy. Tests are based on the fact that each parent contributes a random 50% of an animal's genetic makeup. Genes don't come from anywhere else.

Verification may be based on techniques such as blood typing or DNA typing ( eg. fingerprinting, microsatellite analysis). Use of DNA typing is generally more accurate since it is based on direct comparison of the genetic code of an animal rather than the products of its genes.

[Note: Certain conditions may influence the accuracy of parentage verification such as multiparous births, multiple fertilization, and transgenic manipulation. If any of these cases are suspect then the labs responsible for testing should be informed. Random mutations also take place in populations but generally at low levels not expected to interfere with parentage verification. Other congenital anomalies may arise in the developmental genetic stage but generally do not play a role in animal genetics and should not influence standard parentage verification.]

Pedigree

This is the ancestral lineage of an animal, starting with its parents, grandparents, etc . The pedigree of an animal is its family tree.

History of federal legislation for breed associations

The Act in Canada

The Act respecting the incorporation of Live Stock Record Associations was first passed by Parliament in 1900. It became known as the Livestock Pedigree Act. At that time Canada was a young and growing country with a rapidly expanding agricultural sector. New breeding stock were being brought into the country in record numbers. The concept of recording pedigrees of animals was still relatively new, but had been developing for some time, especially in Great Britain and the United States. There were even a number of breed associations already established or being considered in Canada.

To bring a degree of order and protection to the livestock industry some provinces introduced laws in the mid to late 1800's regarding the marking and branding of animals. Other provincial acts were passed to encourage the improvement and importation of new breeds and to control the movement of breeding animals. However, there remained concern about the lack of standardization and control regarding sale of breeding stock and how they were represented.

Purpose of pedigree recording

Pedigree recording started from the simple observation that "like begets like". The fact that progeny tend to resemble their parents has been recognized at least since biblical times. New ideas began to take hold around the 1700s when certain prominent breeders in Great Britain, demonstrated that knowledge of pedigrees could be employed to breed animals more consistently. By restricting the breeding of animals to only those possessing greater similarity and merit in specific traits, the progeny outcome was more uniform. More predictable matings are more useful and hence profitable. From there, breed societies developed out of a desire to ensure specific rules would be followed to further the development of consistently meritorious animals. This is how many of our modern day breeds began. For breed associations to successfully enhance the worth of their animals it was necessary to ensure that some basic rules would be followed. Nevertheless, at the turn of the century the whole concept of genetic inheritance and breed improvement was still a rather mysterious affair. It was more art than science. Not until the early part of the 1900s when the findings of Gregor Mendel were rediscovered and the theories of Charles Darwin began to gain prominence was it recognized that there might be a stronger scientific basis to breed improvement than originally thought. So while animal husbandry was recognized as the art of skilfully managing animals, at least a part of that management began to be seen as having a predictable scientific basis, termed breed improvement.

Why federal legislation?

The basis for having a federal act under which breed associations can operate is largely twofold. First, the keeping of accurate pedigree information on a national basis is considered critical to the improvement of animal breeds and livestock in general. Second, the establishment of consistent national standards for representation of an animal's genetic background increases the integrity of the information for domestic and foreign trade purposes and provides protection to buyers of breeding stock. It is perhaps important to note that the Animal Pedigree Act was designed primarily to control representation of animals which are going back into the national breeding populations.

The purposes of the revised Act (1988) are stated as follows:

- to promote breed improvement, and

- to protect persons who raise and purchase animals by providing for the establishment of animal pedigree associations that are authorized to register and identify animals that, in the opinion of the Minister, have significant value.

The new Act came into effect May 25, 1988 and represented a major change over previous versions. The Livestock Pedigree Act was last amended in 1952. It focussed primarily on the establishment of breed associations and ensuring a single national authority especially regarding registry activities. The new Act has now also more clearly defined the genetic ground rules for those activities and incorporated new ideas and knowledge relevant to the breeding sector.

Between the years 1952 and 1988, there were significant advances in understanding of the genetics of individuals and of populations. In the 1960s and 1970s many new breeds were introduced to Canada and were often used to grade-up existing populations using reproductive techniques such as artificial insemination or embryo transfer. The field of genetic evaluation flourished and irrevocably moved animal breeding from an art to a science. The Act had to be adapted to properly reflect these changes.

Revision of the Act commenced in earnest about 1985 and was completed in 1988 after extensive consultation. Under the revised Act, promotion of breed improvement was set out as the first purpose and numerous definitions were clarified. Evolving breeds were given special recognition and rules for their development established. Notably, recognition of breed associations incorporated in respect of a distinct breed was made contingent on the breed being accepted as "a breed in accordance with scientific genetic principles".

Animal pedigree associations (breed associations) are incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act and given authority to represent a breed(s) wherein animals are intended for breeding purposes. They have sole authority to manage a public registry for the breed, to issue registration certificates, to establish breed standards and rules of eligibility for registration, and define what is a purebred. There are now approximately 80 breed associations incorporated under the Act representing about 350 breeds. It is hoped that this manual will assist breed associations understand how the Animal Pedigree Act works and what their roles are.

2. Breeds under the Animal Pedigree Act

The Animal Pedigree Act requires that an association be incorporated in respect of a distinct breed "only if the Minister is satisfied that the breed is a breed determined in accordance with scientific genetic principles."

In 1974, the Department of Agriculture created an Advisory Committee with responsibility to establish criteria for the eligibility of new breeds of livestock in Canada. The Committee suggested that new breeds be accepted which met the following criteria:

A population of animals propagated within a pedigree barrier which produces progeny possessing both a good degree of genetic stability as evidenced by phenotypic uniformity and performance levels for one or more economically important traits that offers a meaningful advance over breeds already recognized and/or established.

The key consideration for a distinct breed is the requirement for genetic stability. In practice, this requires that the pedigree background as well as the phenotypic (observed) characteristics of multiple generations can be assessed. Therefore, consistent with genetic principles, a distinct breed is a group of animals all coming from a common foundation population which exhibit recognizable breed characteristics in a uniform fashion.

Foundation stock

Foundation stock animals are referred to in the Animal Pedigree Act as being, "in relation to a distinct breed, [means] such animals as are recognized by the Minister as constituting the breed's original stock."

The starting basis of a sound registry system is twofold.

First, the foundation or original stock must be defined. In practice, each breed represented by an association under the Animal Pedigree Act should have a physical description which establishes a minimum requirement or range for specific distinguishing characteristics of the breed. On this basis, the animals which meet the criteria are selected and constitute the foundation stock for a newly-recognized breed in Canada. Where established registries exist elsewhere in the world for a particular breed, it may be desirable to treat its registered population prior to a fixed date as the foundation population (see Chapter 4 - Recognition of Foreign Registries).

Second, all registered animals must show a relationship to the foundation population. A registry is really a pedigree tracking system in which rules of eligibility are applied. Under the Animal Pedigree Act no animal may be declared purebred if it does not carry at least 7/8ths relationship back to the original foundation stock or to other registered purebreds of that breed. To register animals which are less than purebred, the association must indicate in its by-laws the definition of purebred and must issue certificates which specify the percentage purebred. In essence, by defining the foundation population and ensuring that all registered animals trace back to them, assurance is given that progeny will exhibit the expected standard characteristics of the breed. [Note: In other countries, registries may not always apply rules of eligibility that enforce relationship back to a common foundation and/or apply breed standard requirements. In such cases it may be more appropriate to refer to them as books of record rather than as registries in order to distinguish the two.]

Breed standards

Breed standards in a registry are those characteristics that give recognition to a breed. They are largely applied to traits of physical appearance and visual distinctiveness. Breed standards in respect of registry systems should refer to the range of trait expression considered acceptable for the breed rather than to the ideal animal. Breed standards may include certain performance characteristics and can also be expressed to include or exclude specific genetic conditions. For example, the breed standards for a breed of cattle such as Angus may require the polled condition, or absence from certain genetic disorders.

Breed standards are the basis for recognition of the initial foundation stock of a distinct breed under the Animal Pedigree Act. This is the case for either a breed newly imported to Canada or a breed which has been newly evolved. Adherence to specific breed standards may continue to be enforced through application of rules of eligibility for registration. This is especially common in newly established breeds so that selection pressure gets directed towards helping generate a more uniform breed population. Use of rules of eligibility to enforce breed standards is not as common for well established breeds when they are already considered to be adequately uniform and stable. Enforcing pedigree background may be the only criterion needed for eligibility for registration. This allows relatively more selection pressure to be put on economically important performance traits.

However, where grading-up is permitted, breed associations should be especially attentive to ensuring that breed standards are not compromised through low-level introduction of characteristics from other breeds. For example, it may be necessary for an association to re-introduce rules of eligibility which exclude certain colour variants from the population. Breed standards give uniqueness and recognition to a breed and are important to a registry and to producers of seedstock.

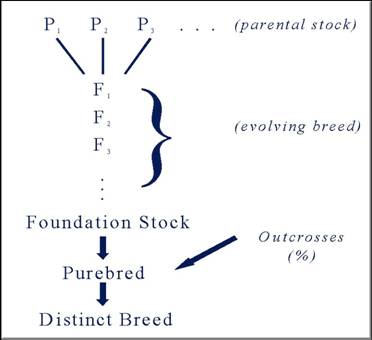

Evolving breeds

The Animal Pedigree Act also allows recording of animals evolving towards a new breed. Typically, selected parental stock are mated to produce a first generation cross (F1) and each successive generation is inter se mated (amongst each other). In the process, selection pressure is put on the evolving breed by removing those animals which do not conform to the established breed characteristics. Animals which do conform are promoted as parents of the next generation. After a number of generations of such breeding, a genetically stable population is eventually achieved which exhibits a uniform set of characteristics or breed standards. These can then be considered as foundation stock for a distinct breed. Development of a new breed can take many routes. The following is a stylised diagram showing development from an evolving to a distinct breed.

Parental Stock - starting genetic resources.

Parental stock may be from several established breeds, a line(s) of animals within a breed having distinct characteristics, a population of animals bred in isolation, etc . Choosing the correct parental stock is critical to the outcome of new breed development, trying to seek the correct mix of adequate genetic variability for performance (marketable or economic) traits and enough uniformity for breed standard characteristics.

Objectives:

- Restrict parental stock to those animals having desirable traits which are expected to contribute positively to the net merit of the new breed.

- Ensure a sufficiently broad genetic base with enough genetic variability to permit breed improvement.

- The new breed should be unique to others in the species; therefore, choose parental stock which collectively have those characteristics already and avoid those with characteristics which will require excessive culling to remove.

Evolving Breed

This is the population of animals deriving initially from the parental stock, mated amongst each other and which possess increasing similarity. Each generation should be culled according to increasingly rigorous standards. By the third and fourth generations there should be obvious genetic stability with respect to the target breed standards, but it may also depend on the traits chosen. Generations F1, F2, ... refer to the first, second, etc . filial generations following the parental generation. Filial generations are numbered as one higher than the lowest parent generation. Some examples follow;

F3 x F3 --> F4

F1 x F2 --> F2

F1 x F4 --> F2

Purebred x F2 --> F3

[This combination possible once recognized as a distinct breed.]

Foundation Stock

Depending on which traits are chosen to be the defining breed characteristics, this is the population selected to become the foundation for a new distinct breed. For example, highly heritable traits may achieve reasonable genetic stability within three generations while lowly heritable traits may take five or more generations. The number of generations will also be influenced by how genetically variable the initial parental stock are, the degree to which undesirable traits need to be culled out of the population, and the intensity of selection applied in each succeeding generation. Application must be made to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for a group of animals to be recognized as foundation stock for a new distinct breed.

Optional structures for breed associations

Introduction

The Animal Pedigree Act allows for incorporation of breed associations (animal pedigree associations). The main purpose of an association is the registration of animals and keeping of pedigrees. This entails maintaining a central registry for pedigree information, issuing certificates of registration (or certificates of identification for evolving breeds) and establishing breed standards and rules of eligibility. Approval is given to associations where it is expected that the keeping of pedigrees and other records of a breed "would be beneficial to the breeders and to the public-at-large."

Applicants must also be able to demonstrate that they "represent the breeders throughout Canada" of the breed in respect of which they are seeking incorporation. In order to be able to function in a democratic fashion, they must be able to demonstrate they can represent the majority of breeders and also address the concerns of the minority. Breed associations are not exclusive clubs. They are non-profit corporations which are federally mandated to administer the affairs of their breed in Canada in a democratic fashion and in accordance with the Act, their articles of incorporation and their by-laws.

Incorporation under the Animal Pedigree Act

The Animal Pedigree Act was established to meet the needs of animal breeders desiring to standardize the recording and representation of pedigrees on animals going back into the breeding population. It is not mandatory that breed associations be incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act, but it addresses some particular needs of the breeding industry. There are also other statutes under which associations may incorporate and other alternatives though, some of which are discussed below.

In general, the legal process of incorporation confers upon an association many of the same rights and obligations as a person. It may enter into contracts, own land and other properties in its own name, and sue or be sued in the courts. As with other corporations, breed association members have limited liability. Financial liability of members is limited to the amount of fees due the association. Directors, officers and employees are also not personally liable for actions taken on behalf of the association, when done in good faith. A general benefit of an incorporated body is that it can carry on as a legal entity even after the founding members depart.

What are the advantages of incorporation under the Animal Pedigree Act?

- All associations must meet minimum requirements for establishment of rules of procedure, membership, public representation of animals, definition of purebred, etc . [see section 15 of the Act]

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada must review and approve any by-law changes before they come into effect. The review process helps ensure consistency with the Act and other by-laws, and helps breed associations develop clear and workable by-laws.

- Recourse to the Canadian legal system for enforcement of the offences section of the Act. The offences under the Act are for the most part unique, and allow action to be taken in instances additional to those, for example, under the Criminal Code. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police provide enforcement for the Act. [Note: Canadian law applies only within Canadian boundaries.] Additional enforcement provisions are contained in the Act whereby the Minister may request an inspection or inquiry if deemed necessary. Breed associations are primarily responsible for enforcement of their own by-laws.

- Only one association in Canada may establish a definition of purebred, maintain a public registry and issue certificates in respect of a breed. This allows the association to present a public image of the breed which is consistent throughout Canada.

What if associations are not incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act?

- If a breed is not recognized under the Animal Pedigree Act then it is possible for any group of breeders to apply to be incorporated for the purpose of representing that breed. [see section 2.3 - Incorporating a New Breed Association]

- If the breed is not recognized under the Animal Pedigree Act then anyone can print certificates, keep pedigree records purportedly for the breed, declare animals purebred, etc . No single standard is necessary.

- Without an association incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act there no recourse to the law for violations of rules regarding pedigree recording and public representation of pedigrees as embodied in sections 63 to 67 of the Act.

- Without a standard recognized body, exports may be more difficult. For example, the European Union (EU) has established a directive for the importation of breeding stock. Breed associations incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act are recognized by the EU .

What are some alternatives to incorporation of a new breed association under the Animal Pedigree Act?

Some groups are too small to incur the overhead that comes with meeting the requirements needed to maintain a national association. Some have little interest in breed standards, breed improvement or selling animals as breeding stock and simply want to keep animals as commercial animals or as pets. Others prefer to maintain proprietary control of all breeding animals and standards and are not interested in a democratically operated national organisation. The Animal Pedigree Act may or may not be appropriate in these cases. The following are some alternatives:

- The Animal Pedigree Act established a General Stud and Herd Book which is maintained by Canadian Livestock Records Corporation for breeds where no association exists. This option is primarily intended for instances in which there are only small numbers of registrations per year. However, the necessary conditions must first exist for the breed to be recognized by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada under the Act.

- The Canada Corporations Act (for non-profit corporations) and the Canada Business Corporations Act (for for-profit corporations) are administered by Industry Canada and allow incorporation for business purposes. Provincial options exist as well.

- Finally, registration may have no benefit for some. Registration is voluntary. If it does not enhance the worth of the animals or their progeny then serious consideration may need to be given to dropping entirely the concept of registration. For those who still like the concept of a certificate to identify an animal, but without all the attendant obligations that come with registration, there are alternative services available for non-recognized breeds.

Options under the Animal Pedigree Act

For breeds that may come under the Act, there are numerous options for an association to consider. Some of these are outlined below.

Single vs. Multiple Breed Association

The Act permits breed associations to represent either a single breed or multiple breeds of the same species. An association's Articles of Incorporation designate the breeds which it is authorized to represent. Amendment of Articles of Incorporation to add or remove a breed requires the membership to be consulted in writing (see sections 20 and 21 of the Act). A minimum 25% response is required and 2/3rds majority of those responding must be in favour of the change. The Act also allows for merging of associations, splitting into separate entities or dissolution.

The most obvious advantage of having a single association to represent multiple breeds is that overhead costs can be reduced per unit of business by sharing administration. There may be other benefits such as more effective sharing of ideas, research and market development efforts. The disadvantages of representing multiple breeds are that the governance structure can be more complicated, and if not managed effectively, complaints can arise that too much time or resources are spent on one breed(s).

Some existing multiple breed associations incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act are the Canadian Kennel Club, Canadian Sheep Breeders Association, Canadian Swine Breeders Association, and the Canadian Goat Society.

Distinct vs. Evolving Breed

When the revised Animal Pedigree Act came into effect in 1988 it included for the first time a category to recognize evolving breeds.

A distinct breed must be essentially a genetically stable population with a common origin and history. Certificates of Registration may be issued and a definition of purebred established for the breed. Foundation stock are the original stock recognized of a distinct breed. All other purebred animals must be able to demonstrate relationship to the foundation stock or to other purebred animals on their certificates. Animals of a distinct breed which do not meet the criteria for recognition as purebred may only be issued certificates which indicate the percentage purebred.

An evolving breed has either not reached the point of being genetically stable or for lack of evidence it cannot be confirmed. Since the essence of a registry system is that it allows consistent tracking and reporting of pedigrees which improves confidence in the genetic outcome of specific matings, evidence of genetic stability across generations is critical. Under the Animal Pedigree Act, an evolving breed can be formally recognized and Certificates of Identification may be issued. Once adequate information has accumulated and there is evidence of genetic stability, an association may request that Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada recognize the breed as a distinct breed.

Registry Operated by Association, Canadian Livestock Records Corporation, or Another Association

Anyone who has tried to trace their family tree knows that registry information can quickly become very complicated. Beyond a few hundred animals, tracking of pedigree information becomes an extremely onerous task and needs to be computerized. The nature of the information collected demands consistent verification usually requiring sophisticated software and regular maintenance and upgrading. This requires a financial investment but also a reasonable degree of competence of registrars to ensure the integrity of the database. The Animal Pedigree Act allows three alternatives for operation of registries.

- A registry may be operated directly by the breed association authorized to represent the breed under the Act. The registrar is directly responsible to the association and manages the registry in accordance with the by-laws and the policy and procedures established by the association.

- An association may become a member of the Canadian Livestock Records Corporation (CLRC). The CLRC was established as a statutory corporation in 1988 (founded in 1905) and maintains registries for over half of all the incorporated breed associations. In addition to maintaining registries, the CLRC is equipped to provide other services required by breed associations.

- An association may authorize another breed association (also operating under the Animal Pedigree Act) to register animals on behalf of and in accordance with the rules of the association incorporated in respect of the breed.

Seedstock vs. Commercial

Should a breed association register just purebred seedstock or animals destined for non-breeding use as well? The Act was established for the purpose of enabling breed associations to set up registries for recording pedigrees of animals intended for breeding purposes. However, the actual seedstock population in almost every species is relatively small, especially given the use of modern reproductive techniques. This makes it critical for the services of breed associations to be seen as useful to a wider population. Depending on the species, commercial usage may include meat production, wool, fur or fibre production, draft, use for pet or recreational purposes, or for racing. Whatever the end use, the commercial market should be the ultimate beneficiary of a credible registry system.

There are a number of ways in which breed associations have adapted their registries to apply or be attractive to a wider population.

- Inclusion of performance information into registry databases and on certificates.

- Enhanced collective reputation of purebred breeders. This may be due to extra service provided by member breeders, healthy and productive animals, marketing efforts of the breed association, links to international sources of seedstock, etc .

- Participation of breed associations in key activities of use to commercial markets. These may include performance competitions ( eg. bull tests, racing, eventing), judging, training, etc . Many breed associations have been successful in having possession of registration certificates made mandatory for participating in these events.

- Expansion of the registry to include part-bred or percentage animals where these animals are important in the commercial markets. The Act allows issuance of certificates for animals which are less than purebred so long as the certificates indicate the percent purebred.

Registries generally function as tracking systems for pedigrees of animals that are potentially to be incorporated back into the breeding population. Other animals not used to produce seedstock technically do not need to be registered. However, registration of commercial animals may be attractive depending on how successful an association has been at expanding the appeal of its services and its reputation as a purveyor or guarantor of animals which meet the needs of the market.

Registry vs. Breed Improvement

The first purpose of the Animal Pedigree Act is to promote breed improvement. A registry can be useful to breed improvement programs by ensuring the accuracy and completeness of pedigree records. However, associations can also add value to their pedigrees by recording performance information. This can be used for genetic evaluation and selection and incorporated into registration certificates. Many associations have a long history of performance recording. Others are less familiar with the benefits and have not realized the full potential of the pedigree information they have collected. Registries and breed improvement are complementary.

Incorporating a new breed association

The Animal Pedigree Act

The Animal Pedigree Act received royal assent on May 25th, 1988 and replaces the former Livestock Pedigree Act.

The stated purposes of the Animal Pedigree Act are,

- to promote breed improvement, and

- to protect persons who raise and purchase animals by providing for the establishment of animal pedigree associations that are authorized to register and identify animals that, in the opinion of the Minister, have significant value.

According to the Act,

The principal purpose of animal pedigree associations shall be the registration and identification of animals and the keeping of animal pedigrees.

These stated purposes express the ultimate authority assigned to the Animal Pedigree Act under which breed associations may be incorporated and exercise their power. Any associations wishing to be incorporated under the Act must demonstrate their activities will be consistent with these purposes.

Considerations for Incorporation

Section 8 of the Animal Pedigree Act sets out the requirements for submission of articles of incorporation. There are no regulations specifying the prescribed form in which articles must be submitted. All the information required under section 8 must be provided, but applicants should contact the Animal Registration Officer to determine whether more specific guidelines may exist. In addition to the specific requirements under section 8 needed for applications, section 6 stipulates requirements which must be met to the satisfaction of the Minister before incorporation. Re-stated here, the requirements are as follows:

- Each breed must be defined in accordance with scientific genetic principles either as a distinct or evolving breed:

- For each distinct breed it must be clearly demonstrated how the breed is distinct and recognizable.

- For each evolving breed a clear description of the physical resemblance and genetic makeup of what it is intended to evolve into, must be provided. There should also be evidence that the creation, with genetic stability, of the new breed is possible. This will be judged on the basis of known genetic principals and reproductive plans;

- To be recognized as a distinct breed, there must be demonstration of:

- a foundation population of animals under inter se breeding having no amount of outcrossing greater than 1/8th;

- pedigree information for foundation animals with evidence they meet the minimum breed description requirements, and demonstrated genetic stability across no fewer than 3 generations.

- An explanation must also be provided to show to the Minister:

- in what way each new breed could be considered of significant value or useful;

- in what way the keeping of pedigrees and other records for this breed would benefit breeders and the public-at-large;

- that the effective foundation population of the breed(s) being represented is adequate to permit the first purpose of the Act, namely breed improvement, to be achieved. Factors that may be taken into account include the effective population size, number of bloodlines represented, degree of inbreeding, reproductive isolation and the genetic health of the population.

- An association must demonstrate that it represents breeders throughout Canada. This may be done by placement of advertisements in publications giving notice of intent to incorporate a Canadian association under the Animal Pedigree Act in respect of a new breed(s). Comments or expressions of interest should be requested. These may be reviewed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

- Applicants for incorporation of an association must number at least five qualified persons, being at least eighteen years of age and being Canadian citizens or permanent residents within the meaning of the Immigration Act, 1976.

- The Articles of Incorporation must follow the requirements of section 8 of the Animal Pedigree Act. This includes submission in triplicate of articles with the name of the association, names and addresses of the applicants, first directors and officers, and the name of the breed(s). Applicants should first contact the Animal Registration Officer regarding specific details of the application. Following incorporation, the association will be given one year in which to submit by-laws.

3. Governance of breed associations

Introduction

Incorporation of breed associations under the Animal Pedigree Act is voluntary. Associations are approved for the principal purpose of operating a breed registry which includes registration of animals, storing of pedigree information and issuance of certificates and other proof of pedigree background. Breed registries are essentially databases which function like family trees for domestic breeds of animals. The legal authority of a breed association comes from the Act and the by-laws which are in effect. By-laws are only in effect once approved by the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Members are bound by the bylaws of the association.

Besides the operation of a registry, associations also exist to improve and promote their breed(s) and to generally further the common interests of breeders. There are benefits and obligations for associations which are incorporated under the Act; primary among them is to act in a democratic fashion. Helpful guidelines for parliamentary procedures and the democratic conduct of the affairs of associations are available from libraries and bookstores. A list of references is provided in Chapter 10 of this manual.

Breed association responsibilities

A breed association is given legal authority under its Articles of Incorporation and By-laws to administer the association's affairs in accordance with the Animal Pedigree Act. The Act requires by-laws to be made which establish a democratic basis for representing breeders. It also anticipates that breed associations have responsibility for the protection of the interests of persons who may purchase animals registered under the authority of the association. Rules of membership must be clearly detailed in the by-laws as must the rules of eligibility for registration and the procedures to be followed in application for registration. The Act also sets out other items which must be contained in the by-laws. The by-laws bind all members.

Although associations provide service to members, as the sole authority to register a breed in Canada they must also not deny registration or transfers except in specific circumstances.

The exceptions are as follows [see Section 61 of the Act]:

- non-payment of fees;

- contravention of by-laws regarding,

- eligibility for registration,

- individual identification ( eg. tattoos, microchips, etc .), or

- keeping of private breeding records;

- contravention of,

- the Animal Pedigree Act or its regulations, or

- the Health of Animals Act or its regulations relating to the identification or testing of animals.

Note that membership dues are different from fees. Fees are paid for services. Dues are paid for membership privileges. Since registration can not be denied to persons who either do not wish to be a member or for various reasons may be denied membership, many associations have adopted special fees for non-members. These are usually set at double the rate for members.

Breed associations have responsibility to maintain the integrity of pedigree information. Upon incorporation, they also accept responsibility to manage the business affairs of the association in a reasonably prudent fashion. All funds (including profits and other accretions) of the association are to be used only for the furtherance of the purposes of the association. Audited financial statements are to be submitted annually to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada along with a list of directors and officers of the association and where appropriate, the names of delegates to Canadian Livestock Records Corporation (section 60). The association must also send to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada notices of meetings setting out proposed amendments to its by-laws, a copy of the annual report after each annual meeting, and the proposed amendments (see chapter on By-law Amendments and also the Checklist at the end of this chapter).

The democratic process

Breed associations are expected to operate in a democratic fashion. The Animal Pedigree Act establishes minimum guidelines for creating by-laws which will promote a democratic process. Substantially more work is required though, to develop an effective set of rules and procedures.

The dictionary defines democracy as a form of governance in which political power resides in all the people and is exercised by them directly or indirectly through elected representatives. It is a system in which the will of the majority must be carried out, but the minority must also be heard and its rights protected. To achieve this the membership must be well informed, motivated, dedicated to a common goal and acting with good intent. An effective democratic process also requires participation.

The by-laws of breed associations guarantee certain rights of membership. However, there are other rights that may go unstated. For example, full members of any democratic organisation should be entitled to all of the following rights (from Procedures for Meetings and Organizations, Kerr & King):

- to receive adequate notice of meetings, newsletters, and regular mailings;

- to participate in debate and to exercise one vote (or a weighted vote) on motions;

- to nominate candidates and to exercise one vote (or a weighted vote) in elections;

- to abstain from voting, or not to use all available votes in a multiple choice vote;

- to stand for elected office;

- to call a special general meeting;

- to have access to the books of the organization;

- to guard against infringement of the rules of the organization and of parliamentary procedure.

Breed associations must also be able to function efficiently. Four areas which are key to an effective association are the proper conduct of meetings, voting, committees, and management of the day-to-day affairs of an association. General comment will be made here about each.

Conduct of meetings

Associations must have by-laws which specify the time, place, quorum, procedures for calling meetings and procedures for conducting the business of meetings. Regular general meetings are not generally practical for breed associations representing members across Canada. Most associations have an annual general meeting and the rest of the affairs of the association is conducted by a board of directors which meets more frequently. There may also be regional groups which hold meetings on a regular basis.

Annual general meetings

Annual general meetings provide a forum for committees and officers to report on their activities of the past year. It is important that members hear account from and be able to question the officers on how they administer the affairs of the association. The annual meeting is also where officers are usually elected and committees are struck, unless such has been done in advance by mail ballot. Since the annual meeting tends to be the main gathering of the general membership during the year it is also the best opportunity to discuss the general goals and objectives of the association. Therefore, the Board of Directors, officers and committees should be adequately prepared to present their reports and manage the agenda so as to avoid excessive time being spent on minor details.

Special general meetings

Special general meetings allow a Board of Directors to address particularly urgent issues such as a critical amendment to the constitution or the replacement of an officer. It also permits a group of members who are unsatisfied with the administration of the association to introduce substantive issues or to request reports from officers or the Board. In either case, special general meetings are restricted to considering only those issues specifically on the agenda circulated with the notice of meeting.

Notice of meetings

An association must have by-laws which specify how meetings are called. Notices of meeting must clearly indicate the date, time and place of the meeting. The following are some other issues to be considered for calling of general meetings:

- Length of time prior to the meeting should be such as to accommodate normal postal delivery, time for members to review and consider the agenda and time to make travel arrangements at more favourable rates.

- Are proxies allowed? If so, proxy forms should be supplied with the notice of meeting.

- Is the notice of meeting sent as a separate mailing or accompanying a circular? If it is combined with a regular breed publication, the time required for publication may be an important factor.

- How much time is being given to submit proposed amendments and to review proposals? For example, it would be impractical to indicate that a notice of meeting with by-law amendments shall go out the same day as the last day for submitting proposed amendments.

Meetings must serve the broadest interests of the association and it is important to have a proper notice of meeting to ensure members are able to participate fully in the affairs of the association.

Procedural rules

Associations vary in the degree of formality used in meetings. Larger meetings generally require more formal procedures to be followed. Formal procedures help ensure that topics of discussion are properly managed, that the will of the majority is carried out and that the minority is heard and its rights protected. In small committees, by contrast, it is not uncommon to almost completely dispense with formalities.

Meeting procedures should facilitate discussion, full participation and decision making. Therefore, parliamentary rules may need to be adapted to ensure the business of meetings is conducted fairly, efficiently and effectively. Regardless of how meetings are managed, associations must still ensure a proper record of decision is kept. Special attention should be paid to the number of eligible voters, quorum requirements, and if majority vote is obtained to render decisions valid.

Procedures for voting

The objective of a vote is to determine the will of the majority. Votes are held to elect directors and officers, to amend a constitution, to establish adhoc committees or other working groups, to accept reports, to approve changes in administrative procedures and rules or to approve expenditures. Other votes may be taken on procedural issues, bestowing of honourary status, etc . Every association must have by-laws respecting the election of directors and officers and the filling of vacancies.

Certain decisions require a majority approval of two thirds or more of eligible voters, such as for amendments to by-laws. A record of the number of eligible voters present and exact vote counts should be kept for these major decisions. Vote counts should be submitted to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada with the requests for amendment to the by-laws.

Requirements for amendment of articles of incorporation of an association are covered in sections 20 and 21 of the Animal Pedigree Act. These votes are usually made to change the name of an association or to add or remove breeds. The membership must receive mail-in ballots, over 25% must return the ballots and a two thirds majority must be obtained.

Majority

There are numerous definitions of a majority. Associations should specify the definition of a majority in their by-laws. Is it the majority of votes cast, majority of eligible voters present, or the majority of total eligible members? The voting majority required to elect directors may also differ from that required to amend the by-laws. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada will request evidence that a majority was obtained before by-law amendments receive approval. Note that by-law amendments, as well as amendments to articles of incorporation, require a two thirds majority vote to be approved.

Proxies

Proxies may be used only if permitted in the by-laws. The conditions under which proxies may be used must be clearly specified. Proxies can be a useful tool in a national organisation where distance is a factor restricting participation. Proxies may also be important to ensure that a quorum can be achieved on votes of major importance. However, they can also be misused if rules are not clearly specified. For example, proxies should clearly specify the meeting for which they apply rather than making them generic. Kerr & King (1984) also recommend, "that an individual should decide on an issue after hearing and participating in the debate. If specific notice of motions and relevant documentation are not received prior to a meeting, it is better not to exercise the vote rather than give a proxy." Proxies may not be used for board meetings.

Mail-in vote

Mail ballots permit the entire membership to vote on an issue rather than only those who attend meetings. National organisations sometimes have difficulty getting strong, representative participation at meetings. This may become a concern when,

- voting takes place on a contentious issue where many more people would like to participate than can attend the annual meeting,

- meetings are held in a region where positions are suspected of differing from those held nationally, and

- meetings are organized at a time or place that may prevent groups of people from attending who could be adversely affected by the amendment.

Rarely is it possible to have meetings which address everyone's needs. Therefore, mail-in votes present an opportunity to reach the entire membership. This may be especially useful for votes on major issues.

If mail ballots are to be used, procedures should be outlined in the by-laws indicating when and how such a vote may be called. There are some drawbacks to a mail ballot. Here are a few concerns that have been raised.

- A mail ballot could remove one of the main reasons for attending the annual general meetings. If we have a mail ballot we risk even fewer members participating than now.

- Mail ballots cost money. We can't afford to spend more money than we already do on the annual meetings.

- The membership needs to discuss the issues before being able to vote knowledgeably. A mail ballot doesn't offer the same opportunity for discussion as a meeting.

These are all valid points. Here are a few ways to address the problems.

- Arrange mail ballots to overlap with the timing of annual general meetings. If ballots are sent out with the regular notice of meeting, cost of mailing can be kept to a minimum. The return date for ballots can be after the annual meeting so that attendees have a chance to fully discuss contentious issues and relay the results back to other interested members. Therefore, meetings can still serve as important opportunities for discussing by-law amendments as well as other issues.

- Mail ballots should be prepared with accompanying background information and explanation, including a sampling of views (pro and con) on the issue. The membership must be able to make an informed decision. Although it is true that many issues often become clear only after discussion, this may also be due to lack of advance preparation. By having to put an explanation in writing and solicit views and comments of directors and other interested parties in advance, a mail ballot may actually serve to better clarify complex issues for the membership.

- The whole membership usually has one opportunity per year to meet as a body. This is a good opportunity to discuss broad policy options, the goals and objectives of the association and to critically assess the association's performance. However, not every association uses the opportunity wisely and some get into endless debates about minor points. Mail ballots require advance preparation, especially by the board of directors, so may allow the annual general meeting to focus more of its effort on policy alternatives rather than administrative, procedural or technical detail.

Committees

Most of the detailed work of an association often gets done in committees. Committees can function in an administrative or executive role, or as advisory bodies. They may be established in the by-laws as standing committees or may be appointed by the board of directors for a fixed period of time or until they have completed their duties. To be effective it may be advantageous to avoid committees which are too big. Too many committees also tend to drain associations which rely on volunteer effort and can be unwieldy to manage for reporting and decision making purposes.

Committees may exercise no authority beyond their terms of reference. Where committees are established in the by-laws of an association, their make-up, functions and reporting requirements should be specified. A more detailed terms of reference can either be included directly in the bylaws or procedures for their establishment indicated in the by-laws. Lack of sufficient detail has sometimes caused problems, for example, where it is unclear if the executive committee or the board of directors should be making certain decisions. Is it obvious where, when and on what issues reports should be made to the board for its decision? Breed associations need to ensure that the by-laws are clear on who has authority to do what.

Committees often operate on an informal procedural basis but are expected to report on a regular basis or as otherwise requested. Therefore, regardless of how informal the meetings may be it is still necessary to have a proper record of proceedings. Committees are directly responsible to the body that creates them.

Management

The by-laws of breed associations establish the broad framework for management of an association but often require further details to be specified. Associations should have some type of policy and procedures manual or other guidelines. This is especially necessary where secretaries act on a volunteer basis and change often. Where a general manager or chief executive officer is hired by a breed association it is still no less critical to clarify how various situations in the day-to-day management of the association are handled. The board of directors is elected by the membership to manage the affairs of the association and must be knowledgable of how it is being done.

Board of directors

The Board of Directors reports to and is directly responsible to the general membership. The board is usually expected to draft policy which can be considered by the membership, to appoint people to carry out specific functions and approve criteria for hiring as necessary, to be responsible for the prudent management of the finances of the association and to carry out specific functions as indicated in the by-laws or otherwise delegated to it by the membership. The composition of the board, the method for election of directors, powers, duties and functions must all be specified in the association by-laws. This means that the board is delegated specific authority by the membership for administration of the affairs of the association between general meetings.

A Board of Directors must act as a body and is governed by the association's articles of incorporation, approved by-laws and the Animal Pedigree Act. The president officially represents the association to outside persons and other bodies. However, no director may act independently on behalf of the corporation unless given specific authority by the board to do so. Decisions of the board made in accordance with its proper authority, are binding upon both the board and the corporation.

Executive committee

An Executive Committee may be established where it is considered too difficult for the full board of directors to meet on a regular basis. It is common for associations to have an Executive Committee which is responsible for the day-to-day affairs.

The membership of the committee is derived from the board and officers of the association. Its powers should be defined in the by-laws or delegated to it by the board, if so permitted in the by-laws. The Executive Committee only has powers as permitted through the by-laws.

Officers

The powers, duties and functions of officers should be specified in the bylaws as should their manner of election. The detailed terms of reference ( i.e. job description) of officers may be further decided by the board in accordance with the objectives and needs of the association. The standard list of officers usually includes a president, past-president, vice-president, secretary and treasurer. In smaller non-profit corporations it is not uncommon for the same persons to be directors as well as officers of the corporation.

Liability

The Animal Pedigree Act gives the protection of limited liability (see Sections 14 and 50 of the Act) to officers, directors and employees of an association who are acting on its behalf in good faith. Therefore, although an association can be sued, persons who are acting in good faith in the exercise of their powers or performance of their duties and functions are not personally liable.

Financial liability of members of an association is limited to any fees owing to the association and any amount that may be due in respect of services provided.

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest is of primary concern where a person uses either inside knowledge not available to others or his position within the organisation to benefit financially. "A director with a personal interest in a matter under consideration by the board must disclose in full what that interest is and usually will be required to abstain from voting on that matter. It has become common practice for a director with a conflict of interest to leave a meeting while the matter is under consideration." (Stanford, 1995)

Association directors and officers must also be cautious about how they handle inquiries to purchase breeding stock. Although it is not usually practical or advisable to forward incoming purchase and sale inquiries to every member, the association should have procedures in place to give every member a fair opportunity to benefit. Increasingly, electronic communication is giving more options to breed associations and these opportunities should be explored. The benefits as well as obligations are expected to accrue to the whole of the membership, not just to directors and officers of the association.

Frequently asked questions

If we send out notices for our Annual General Meeting two days late does that invalidate the meeting?

By-laws are established for a number of purposes, not the least of which is to standardize good practices. For example, if cheaper airflights require booking 30 days in advance, mail takes up to a week to deliver and people require one to two weeks to make arrangements and consider whether or not they can attend a meeting, 60 days notice may be reasonable. Many by-laws are drafted and approved by the membership exactly because they make good practical sense, not because 60 days is such a magic number.

However, once written into the by-laws they become more than just good ideas and they bind every member. It is expected that rules and procedures adopted by the association will conform to the by-laws. Nevertheless, when certain requirements are not met for reasons beyond the control of the association, a judgement call may be necessary. What procedures or circumstances were responsible for the delay? Was this a simple oversight or does there appear to have been intent to manipulate? Were there consequences of the delay that affect decision making? Was it really the intent of the membership which approved the by-law that an Annual General Meeting should be cancelled if notices were sent out at 58 days? Although these considerations may sound reasonable, technically any member also has a right to object to an improperly called meeting and decisions made at a meeting may be considered invalid.

The rules of eligibility for registration don't make sense and the board of directors wants to change them. Can they do that without first going to the membership?

No. The board is bound by the by-laws as is every other member. There are three types of by-laws which must be spelled out in detail. Requirements for membership, rules of eligibility, and procedures to be followed in applications for registration all must be clearly detailed in the by-laws. The board of directors may make proposals to the membership in respect of their amendment but may not act contrary to them. The board remains bound by the by-laws which has been approved by the Minister.

There are other by-laws which may not contain sufficient detailed specifications to account for every situation which may arise. In these cases, the board is delegated authority through the by-laws to administer the affairs of the association. However, its decisions should remain consistent with the established procedures of the association and its objectives.

| Information to be supplied | Timeline |

|---|---|

| Notice of meetings setting out proposed amendments to the by-laws of the association. | To be sent at the same time and in the same manner as sent to members. |

| A copy of the annual report, including an audited financial statement. | To be sent immediately after each annual meeting. |

| A list of directors and officers of the association, and where the association is a member of Canadian Livestock Records Corporation, the name(s) of the association's voting representative(s). | To be sent immediately after each annual meeting and also immediately upon any change, such as a change in address of the association secretary (or General Manager or CEO ). |

| A request to amend either the by-laws of the association and/or the articles of incorporation as the case may be, in accordance with the bylaws and the wishes of the membership as established in a vote. | To be sent as soon as practical after such a vote has been held (see By-law Amendments under the By-laws section). |

| Annual statistics regarding membership and registration activities, specific details of which may be specified from time to time by the Animal Registration Officer. | To be sent as soon as practical after calendar year-end, and preferably before the end of March each year. |

| Note: Where the Act specifies that certain information is to be sent to the Minister, it should be sent care of the Animal Registration Officer who acts on the Minister's behalf. It should not normally be sent directly to the Minister. | |

4. By-laws

Introduction

All breed associations must submit by-laws for approval within one year of being incorporated under the Animal Pedigree Act. No by-law, amendment or repeal has effect until it is approved by the Minister. By-laws give legal authority to an association by which it may conduct its affairs. The by-laws bind every member.

Registration rules of eligibility

Background

Consistent with the Animal Pedigree Act, all breed associations must establish rules respecting eligibility of animals for registration. The rules of eligibility contained in the association by-laws should be comprehensive so as to clearly indicate to the public the criteria by which animals will be included or excluded from registration. For most breed associations, registration is by far the most important activity.

Establishing rules of eligibility

Rules of eligibility for registration are established to achieve two objectives:

- The maintenance of minimum breed standards. These are like trademark characteristics for the breed. Animals that do not meet minimum breed standards which satisfy the broadest description of the breed should not be registered as purebred. Only animals which do conform should be accepted into the breeding population.

- Enforcement of rules on ancestral lineage (pedigree). Animals must have documented proof of relationship back to a common foundation population. This should correspond to the minimum definition of purebred accepted by the association. Animals demonstrating lineage less than purebred requirements must have the percentage purebred appropriately indicated.

Rules of eligibility for registration should be based on genetic criteria. For example, requiring that animals are dehorned as a condition for registration would do nothing to effect a genetic change in the breed; however, requiring that only genetically polled animals be allowed registration would have an influence. Breed characteristics can only be improved if a trait is heritable and inheritance patterns are well understood. As well as traits being heritable, there also must be a balance with other breeding objectives related to improving performance and enhancing overall viability of the population. Therefore, the degree of emphasis on breed standards must be considered carefully.

Where a breed is well established and the definition of purebred is 100% ( i.e. closed herdbook), it is common to reduce or even eliminate eligibility rules related to breed standards and just concentrate on the pedigree. However, there are a number of situations in which a breed association may wish to retain emphasis on breed standards:

- where a breed is not well established and not as genetically stable as desired for certain trademark characteristics,

- where definition of purebred is less than 100% (may be no less than 7/8ths) and grading-up to other breeds is known to diminish certain accepted trademark characteristics, or

- there is a desire to evolve the entire breed. For example, there may be consensus to remove a particular colour variant or a genetic disorder from the population.

Nevertheless, caution should be exercised in establishing rules of eligibility which place undue emphasis on trademark characteristics or other breed standards. The risk of too much emphasis is to limit the effective population size, limit selection pressure on other more economically important traits, limit the ability of the breed to evolve (breeds are dynamic populations), and perhaps even decrease genetic variability in critical traits. Breed associations must recognize that there is also an important role for performance recording, genetic evaluation, and marketing which should be independent of the registry itself.

Breed of improvement

The first purpose of the Animal Pedigree Act is to promote breed improvement. Breed improvement results from selecting certain animals as parents of the next generation and excluding others. Breed improvement strategies may include establishing rules of eligibility for registration which enforce breed standards, culling poorly performing animals, promoting top performers as parents of the next generation ( i.e. selection), and planning matings.

Genetic traits can be roughly separated into those which are considered trademark characteristics (traits which identify the breed such as colour, size, etc .), fitness traits ( eg. fertility, disease resistance, absence of genetic disorders), and other performance characteristics ( eg. growth rate, milk production, fibre quality). Considering the relative impact of breed improvement strategies on these genetic traits, we would find they are not all equally as effective. For example, it is difficult to establish rules of eligibility which will improve a breed's fitness. Registration occurs early in life whereas reproductive and health performance need to be assessed closer to maturity. On the other hand, establishing rules of eligibility to enforce breed standards is probably the best means of ensuring that trademark characteristics of the breed are retained.

Given the emphasis of the Animal Pedigree Act on breed improvement, breed associations have a special role in assisting breeders by providing a balance of tools to improve their animals. The Act allows breed associations to make by-laws (see Section 15(2) of the Act) respecting promotion and establishment of breed improvement programs, inspection of animals for registration and performance standards which must be met. However, caution must be exercised to ensure that registration criteria aren't overused to the point of restricting the breeding population. The main emphasis of registration rules in addition to pedigree requirements should be on the enforcement of breed standards to ensure animals retain their essential trademark characteristics. Therefore, most performance recording programs are additional to the registry system, although participation in performance recording may be considered a prerequisite to registration.

In general, concentration on pedigree background is expected to improve predictability of the animals in a breed. Concentration on the other areas of breed improvement are expected to yield additional benefits.

- Trademark characteristics - enforcement of breed standards, uniqueness

- Performance traits - economic viability, marketability

- Fitness traits - selection differential, breeding viability

Breed associations should carefully consider where they wish to put emphasis for the overall benefit of the breed. What will make the breed most competitive? Over time the emphasis may change so breed associations must remain current with the requirements of the market.

Summary

Rules of eligibility for registration should be kept simple, have a sound genetic basis, and be used to ensure compliance with minimum breed standards and ancestral lineage. It is just as critical to maintain a viable, sufficiently large and diverse population from which to select animals. Performance and marketing issues should be handled separately from the registry itself. When a breed is well established and genetically stable, emphasis on breed standards may be replaced by emphasis on performance traits. These will have a more direct impact on the long-term economic viability and competitiveness of the breed.

Recognition of foreign registries

Breed associations may recognize foreign registries in whole or in part. The effective size of a breeding population is expanded when foreign animals are accessible to Canadian breeders. The benefits of a larger effective breeding population can be realized when imported animals meet the minimum requirements expected of the Canadian registered breed population. They should also be selected based on objective characteristics expected to improve the Canadian breed population. Either an entire foreign registry can be recognized or just the portion considered to be in compliance with Canadian standards.

Full recognition

Full recognition of a foreign registry implies the following;

- The animals registered in the foreign herd book derive from a population with a similar origin and history to the Canadian registered population.

- Animals in the foreign registry have breed standards similar to the Canadian population.

- All animals in the foreign registry are physically identified in a manner which is unique, permanent and positive (easily read and interpreted).

- Rules of eligibility correspond to minimum requirements of the Canadian registered population.

- The foreign registry is centralized to ensure consistent application of its rules of eligibility, unique and consistent pedigree information with an ability to produce registration certificates showing at least three generations of ancestry.

Partial recognition