Message from the Honourable Lawrence MacAulay, Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food

In Canada, we are fortunate to have the capacity and natural resources to produce an abundance of safe and nutritious food. The decisions we make every day about food have a direct impact on our communities, health, environment, and economy. That is why I am honoured the Prime Minister asked me to work with my colleagues and Canadians to develop A Food Policy for Canada. A first of its kind for the federal government, this policy will seek to bring forward a long-term vision for the social, health, environmental, and economic goals related to food. Its aim is to help coordinate federal actions, supporting progress toward the priorities we have collectively identified when it comes to our food systems. A Food Policy for Canada will strive to improve the lives of all Canadians, including the middle class and those working hard to join it.

Consultations have been at the heart of efforts to develop this policy. In 2017, we reached out from coast to coast to coast, asking people to share their priorities for our food system. Our Government also launched a public online survey in May, and hosted a National Food Policy Summit in June to bring together stakeholders and experts. We then travelled across the country during August and September, holding engagement sessions in six regions to hear the diverse views and ideas of Canadians. We listened to farmers, harvesters, food processors, and consumers, and a broad range of organizations active on food-related issues, including health, food security and the environment. We also supported engagement sessions led by three National Indigenous Representative Organizations – the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, and the Native Women's Association of Canada.

Canadians responded with interest and passion. Close to 45,000 people shared their thoughts on what a food policy should do via the online survey and hundreds participated in face-to-face discussions.

This report brings together what we heard. It will shape our ongoing work on the development of A Food Policy for Canada. I want to thank each participant in our consultations for making your ideas known. This is your policy. We will continue to work together with you towards our shared vision for the future of food in Canada. Importantly, A Food Policy for Canada will help move forward on our Government's ambitious growth targets for the agricultural sector and the middle class jobs it provides, while ensuring the benefits are shared by everyone and that we respond to the areas of public trust voiced by Canadians in these consultations.

Lawrence MacAulay, PC, MP

Executive summary

Canadian society faces many opportunities and challenges around the production, processing and consumption of food. The decisions Canadians make as individuals and as a country about food have direct impacts on their health, environment, economy, and communities.

- The agriculture, fisheries, and food sectors are vital parts of the Canadian economy. They have the potential to make more high-quality food available domestically and internationally, contributing to economic growth and job creation.

- Although Canada produces more food than its people can consume, not all Canadians have sufficient access to safe and nutritious food. Some groups such as children, Canadians living in poverty, Indigenous peoples, and those in isolated northern communities, remain particularly vulnerable to food insecurity.

- While Canadians benefit from one of the best food safety systems in the world, rates of diet-related chronic disease are increasing, with associated health care costs. Canadians sometimes face challenges in making nutritious food choices in support of their health.

- The way food is produced, processed, distributed, and consumed can have implications for soil, water, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity. While much is being done to protect natural resources in the production of food, to continue to meet growing demand, environmental conservation is a priority.

In his mandate letter of November 2015, the Prime Minister asked the Honourable Lawrence MacAulay, Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, to develop a food policy that "promotes healthy living and safe food by putting more healthy, high-quality food, produced by Canadian ranchers and farmers, on the tables of families across the country." As well, in October 2017, the mandate letter of the Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, the Minister of Health, asked her to work with the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food to align new regulatory initiatives with food policy.

A variety of food policy models have been developed internationally. In Canada, various stakeholder organizations providing leadership on food issues recognize the importance of national food policy. Key proposals put forward in recent years include the Canadian Federation of Agriculture's National Food Strategy (2011), Food Secure Canada's Resetting the Table: A People's Food Policy for Canada (2011; revised 2015), and the Conference Board of Canada's Canadian Food Strategy (2014).

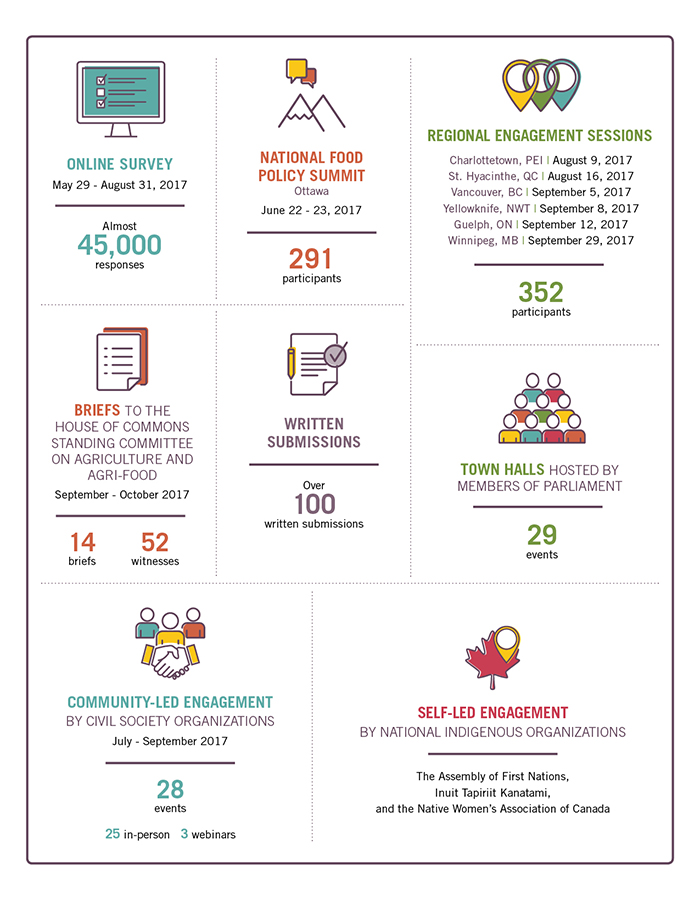

Several federal departments and agencies worked together collaboratively to develop extensive formal consultations towards the development of the policy in 2017, including an online survey, a National Food Policy Summit, regional consultation sessions, local townhall events organized by Members of Parliament, community events held by civil society organizations, and self-led engagement by National Indigenous Representative Organizations.

The Government recognized the importance of hearing from a wide variety of Canadians and stakeholders. Consultations included: organizations representing farmers, fishers, and the food industry; civil society groups, with interests in food security, health, and the environment; academics and other experts; officials with provincial, territorial, and local governments; and Indigenous Representative Organizations.

Input was gathered from Indigenous individuals and organizations through the online survey, national and regional engagement sessions, and civil society engagement. The Government also engaged bilaterally with Indigenous Representative Organizations to identify preferred approaches for Indigenous engagement on the development of the food policy. Government officials also participated in ad hoc engagement events hosted by organizations representing Indigenous communities or interests.

Consultations were designed to elicit views and perspectives of Canadians and stakeholders on the development of the policy, and on their priorities within four themes:

- Increasing access to affordable, nutritious, and safe food, particularly among more vulnerable groups such as children, Canadians living in poverty, Indigenous peoples, and those in remote and northern communities;

- Improving health and food safety — Increasing Canadians' ability to make healthy and safe food choices;

- Conserving our soil, water and air — Using environmentally sustainable practices to ensure Canadians have a long-term, reliable, and abundant supply of food; and

- Growing more high-quality food — Ensuring Canadian farmers and food processors are able to adapt to changing conditions to provide more safe and healthy food to consumers in Canada and around the world.

In this document, these themes are often summarized as Food Security, Health and Food Safety, Environment, and Economic Growth.

The breadth and depth of interest in the consultations and food-related issues are significant. The effort and interest shown by participants in the consultations will have a meaningful impact. The participation is valued and ongoing dialogue on food policy will continue to help to shape A Food Policy for Canada, the first comprehensive food policy developed by the federal government.

With this in mind it is important to note that input was wide-ranging, broad-based, and not always consistent. The report aims to reflect the essence of the ideas and perspectives that were raised during the consultation process but does not attempt to include every comment received and it does not intend to imply consensus on the part of all participants. It presents a summary of what was heard from consultation participants – key messages, perceptions, and suggestions for the food policy. The views expressed are those of participants in the consultation process and should not be construed as representative of the Government of Canada's positions or views.

Input received from Canadians and Stakeholders in 2017

Online Survey

May 29-August 31, 2017

Almost 45,000 responses

National Food Policy Summit

Ottawa

June 22-23, 2017

291 participants

Regional Engagement Sessions

Charlottetown, PEI | August 9, 2017

St. Hyacinthe, QC | August 16, 2017

Vancouver, BC | September 5, 2017

Yellowknife, NWT | September 8, 2017

Guelph, ON | September 12, 2017

Winnipeg, MB | September 29, 2017

352 participants

Briefs to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-food

September-October, 2017

14 briefs

52 witnesses

Written Submissions

over 100 written submissions

Town Halls hosted by Members of Parliament

29 events

Community-led engagement by civil society organizations

July-September, 2017

28 events (25 in-person, 3 webinars)

Self-led Engagement by National Indigenous Organizations

The Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Native Women's Association of Canada

Vision

Participants in the consultations expressed support for a food policy vision statement that explicitly addresses sufficient access to safe, nutritious and culturally-appropriate food, supports and protects the environment, and grows Canada's agriculture and food sectors.

Key perspectives on the principles and vision of A Food Policy for Canada included:

- Including people, systems and leadership as concepts in the vision statement;

- Encompassing all parts of the food system, including producers, processors, fishers, harvesters, distributors, retailers, and consumers;

- Recognizing the linkages among food security, health, environment, and economic growth;

- Integrating the Government's economic growth agenda into policy development;

- Supporting greater policy alignment within the federal government, and intergovernmental collaboration;

- Basing policy development on solid evidence and data;

- Respecting and prioritizing reconciliation with Indigenous peoples; and

- Emphasizing social justice and ethical considerations around food.

Themes

Strong support emerged through the consultations for building a food policy based on the four themes of food security, health and food safety, environment, and economic growth. Many participants spoke about the interconnectedness of the four themes.

Food Security

Priorities identified for increasing access to affordable, nutritious, and culturally-appropriate food in Canada included, among others:

- Recognizing the link between food and cultural identity;

- Increasing food security for all people living in Canada;

- Addressing food security as an issue based on income security;

- Increasing food security in Indigenous and isolated northern communities; and

- Supporting local, community-based solutions to food security.

Health and Food Safety

Priorities identified for improving the health of Canadians, and maintaining food safety included, among others:

- Recognizing food as a key determinant of health;

- Supporting Indigenous and northern health and food safety;

- Enhancing food literacy and improving food labelling; and

- Addressing food fraud – the deliberate substitution or misrepresentation of food for economic gain.

Environment

Priorities identified for the environmental sustainability of Canada's food systems included, among others:

- Including protecting biodiversity in the environment theme;

- Protecting agricultural land and animal and fish habitats;

- Recognizing and monitoring the impacts of climate change and habitat loss on country/traditional foods, particularly in the North;

- Providing more information and training opportunities for farmers and fishers on sustainable practices;

- Reducing food loss and waste across the food system; and

- Continued or increased monitoring on the use of pesticides.

Economic Growth

Priorities identified for future growth of the agriculture and food sectors included, among others:

- Supporting the Government of Canada's ambitious plan to grow Canada's agriculture sector in order to meet the target of $75B in agri-food exports by 2025;

- Supporting sector growth and prosperity at the local and regional levels;

- Promoting innovation, to address existing barriers and adapt to changing market conditions and demands;

- Supporting new entrants into the agriculture and food sectors, with a focus on underrepresented groups;

- Increasing international market access;

- Supporting isolated northern and Indigenous communities; and

- Balancing economic growth with environmental and other priorities.

Priorities cutting across and interconnecting multiple themes

During consultations, opportunities emerged that cut across themes and were seen as important to the success of A Food Policy for Canada by participants. These included:

- Increasing program and policy coherence within the federal government to allow for a more coordinated and collaborative approach to food policy;

- Improving the collection, analysis and sharing of food-related data to support the ongoing development and evolution of the policy;

- Creating a strong governance mechanism including an external advisory body, and inter-departmental food policy committee, and discussions with provincial and territorial governments; and

- Exploring an approach to Indigenous food policy that recognizes, respects, and affirms the distinct needs and cultures of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

What we heard

Canadians' reaction to the development of A Food Policy for Canada has been positive, with many agreeing that there is a need for improved federal coordination on food-related issues and policies. The high level of participation in the consultations, and public dialogue on the development of the food policy, have shown that the issues are wide-ranging.

The findings of the consultations will help to shape A Food Policy for Canada, the first of its kind developed by the federal government.

Vision

Developing a vision statement will contribute to the success of A Food Policy for Canada. The vision statement would ensure the Government of Canada, as well as all stakeholders, focus on what matters most by providing a basis for developing targeted actions.

Three draft vision statements for the policy were presented to participants at the National Food Policy Summit in order to elicit participant feedback:

- Canadians, no matter where they live in Canada, have the ability to access a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious, and culturally-appropriate food;

- Canada's food system is further developed in a way that supports and protects the health of our environment and Canadians, and grows the agriculture and food sectors; and

- Canada is a trusted leader in providing safe, high-quality, and nutritious food through sustainable and successful agriculture and food sectors.

Summit participants expressed broad support for the elements included in these draft statements. They emphasized the importance of including people, systems and leadership in a vision statement, along with food security and protection of the environment. They also signalled that the policy's vision statement should acknowledge the importance of culturally-appropriate food, encompass all parts of the food system, and recognize the linkages among food, health, the environment, and economic growth.

Some participants at the National Food Policy Summit highlighted additional elements they wanted to see in the vision statement, including food sovereignty, food as an issue of human rights, enhanced food literacy, food waste reduction, innovation in sustainable agricultural practices, market diversity and resilience, and thriving local and regional food systems.

There was a strong consensus that the vision statement must include all people living in Canada, regardless of citizenship.

Drawing on feedback from the National Food Policy Summit, a single draft vision statement was provided for subsequent engagement sessions with more inclusive language:

The Canadian food system provides a sustainable food supply so that all people in Canada, no matter where they live, have the ability to access a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious, and culturally-appropriate food, that in turn contributes to their health, and that of our environment and our economy.

Regional session participants provided further input on a vision statement: emphasizing education, food literacy and choice; recommending explicit reference to food sovereignty and food security; and calling for more ambitious and inclusive language. These participants recommended a comprehensive but concise statement that acknowledges the importance of Canadian producers, including those who raise livestock, harvest, fish, and hunt.

Principles

In addition to the draft vision statement, Summit participants were also provided with draft principles, which are proposed to guide implementation of the food policy. Draft principles included that A Food Policy for Canada be inclusive, participatory, collaborative, results-oriented, evidence-based, integrated, systems-based, adaptable, innovative, accountable, and transparent. It was also put forward that the policy should respect and prioritize reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, and support greater policy alignment within the federal government, and intergovernmental collaboration.

Summit participants expressed strong support for all of the proposed principles and suggested additional principles including: policy coherence through cross-sector collaboration and coordination; a systems-based approach; openness to innovation; capacity-building; putting people and communities at the heart of solutions; and respecting the dignity and rights of those most negatively affected by food insecurity.

Summit participants also wanted to include reconciliation as a core principle. Similar support was expressed at the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) and Assembly of First Nations (AFN) engagement sessions. Participants at the ITK session also recommended adding self-determination as a principle, to ensure that Inuit and other Indigenous groups would be included in the development, design and delivery of food-related policies, programming and services that may affect their communities. As well, they noted that a relationship between the Government and Indigenous peoples on food policy should recognize, respect, and affirm the distinct and unique rights and cultures of First Nations, Inuit and Métis, through the development of distinct food strategies. Similar comments were raised at the AFN session.

Working from the feedback received at the National Food Policy Summit, revised draft principles were presented to regional participants for discussion:

- Inclusive: considers the diverse interests and perspectives of Canadians

- Participatory: allows all Canadians to be part of an ongoing dialogue, with a focus on community-based and community-led initiatives, and capacity-building

- Reconciliation: respects and prioritizes reconciliation with Indigenous communities

- Collaborative: enables collaboration among governments and stakeholders

- Results-oriented: based on concrete actions with measurable goals

- Evidence-based: uses best available data, knowledge, and research

- Integrated: recognizes links across themes/priorities

- Policy coherence: moves toward greater policy alignment and intergovernmental collaboration

- Systems-based: uses a systems-based approach (i.e., examines the linkages and interactions between the different elements of the food system) to address complex food issues

- Adaptable: able to evolve, responding to new issues and priorities

- Innovative: open to innovation, both technological and social

- Accountable: with a clear governance structure(s)

- Transparent: governance, decision-making, and monitoring and reporting

Consultations highlighted that principles should be geared towards action and that all concerned parties should be accountable for following the final principles. Some participants voiced that A Food Policy for Canada should complement and not diverge from the Government of Canada's economic growth agenda. Some emphasis was also placed on including social justice and ethical principles in order to ensure the policy reflects societal priorities such as food as an issue of human rights, protection of the environment, individual and public health, and worker and animal welfare. Some participants recommended adding sustainability and education to the list of principles.

Consistent with the proposal for an integrated approach, the cross-cutting impacts of food on health, environment, food security, and the economy, and in some cases, their reciprocal relationship, were widely noted throughout all engagement activities, including the National Food Policy Summit, regional sessions, external consultations, correspondence submissions, and the qualitative online survey responses. Highlighting the importance of an inclusive and collaborative food policy that supports reconciliation, some expressed the viewpoint that a food policy should engage all orders of government, including provincial, territorial, local, regional, and Indigenous.

The policy principles given the most priority in terms of the frequency in which they were raised were adaptability, transparency, innovation, policy coherence, evidence-based, and inclusiveness.

Almost a quarter of respondents to the online survey who expressed an opinion on the relative emphasis to place on the guiding principles selected evidence-based as the most important. It was followed by integrated (22 per cent); consumer-focused (21 per cent); accountable (11 per cent); producer-focused (9 per cent); inclusive (8 per cent); and cooperative (5 per cent).

Themes of a food policy

Four themes for A Food Policy for Canada were presented to participants at the Summit, and regional sessions, and formed the basis for the questions appearing in the consultation tool kits and online survey:

- Increasing Access to Affordable Food;

- Improving Health and Food Safety;

- Conserving our Soil, Water and Air; and

- Growing More High-Quality Food.

There was broad support for all four themes, although some participants felt they could be broader. For example, some participants suggested removing the term affordability from the first theme to broaden the understanding of food insecurity. During the Indigenous engagement sessions, in particular, concerns were raised that the themes do not sufficiently reflect Indigenous-specific issues and considerations – distinct cultural preferences and practices, the importance of country/traditional food, and Indigenous knowledge (including but not limited to traditional ecological knowledge).

Online survey results suggest that the respondents, with three- quarters identifying themselves as being from the general population, were mostly focused on issues that affect them as consumers. Qualitative survey comments focused on increasing access to affordable food (47 per cent) over any of the other themes in A Food Policy for Canada. Quantitative results ranking the four theme areas resulted in "Conserving our soil, water, and air" as the highest priority theme (45 per cent) followed by "Increasing access to affordable food" (32 per cent), then "Improving health and food safety" (13 per cent) and then "Growing more high quality food" (11 per cent). Quantitative and qualitative results suggest that respondents are very concerned with protection of land, rural and remote access to food, local and organic food production, and food costs. They were less concerned with exports, trade, or the Canadian sector's global reputation. More than 10 per cent of respondents reported relying on friends, family, or community organizations for food when they could not afford to buy enough.

1. Food Security

Food security is commonly understood to exist when all people, at all times, have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food for an active healthy life. While Canadians generally enjoy a high quality of life and affordable food compared to citizens in other countries, many still experience some level of food insecurity.

When asked to identify priorities for increasing access to affordable, nutritious, and culturally- appropriate food in Canada, consultation participants identified the following, among others:

- Increasing food security for all people living in Canada;

- Addressing food security as an income issue;

- Increasing food security in Indigenous and isolated northern communities; and

- Supporting local, community-based solutions to food security.

Increasing food security for all people living in Canada

Increasing food security for all people living in Canada was a priority for the majority of those who participated in consultations. When asked to prioritize sub-themes under the food security theme, the majority (65 per cent) of online survey respondents said, "Ensuring that all Canadians can access nutritious food no matter where they live" was of the highest priority. "Making nutritious food more affordable for all Canadians" (63 per cent) and "Supporting the growth of local and regional food production" (58 per cent) were also considered to be of the highest priority by the majority of respondents.

Some participants noted that the cost of food in Canada relative to income is comparatively low on a global scale. There were mixed views on the use of the term "affordable" in this theme. Some stakeholders felt that pursuing affordability of food could either impede production of food or the ability of farms and food businesses to earn reasonable profits. Although affordability was seen as extremely important by some participants, especially those from isolated, northern communities, it was not something that participants wanted to pursue at the expense of food quality and nutritional content. Many participants suggested removing it from the theme title, and instead focusing on ensuring access to and availability of safe and nutritious food. With regard to the term "access", many participants also asked for clearer definitions or qualifiers, and for a distinction between economic and physical access to food.

During consultations many specific calls for the implementation of school food programming were made. Participants thought that school nutritional programs could help alleviate food insecurity. As well, it was suggested that provision of meals in schools can help ensure that children eat a sufficient quantity of healthy food, a concern not limited to lower income groups. There were also calls for revised school lunch guidelines, including ensuring students have enough time to eat.

Addressing food security as an income issue

Participants believe that income insecurity leads to food insecurity, and called for policy solutions that address income disparities and poverty. A wide range of participants, from civil society organizations to service providers, called for short and long-term actions to address the issue that would go beyond simply making more food available through food banks. Rather than focusing only on lowering food prices, there was support among some participants for the establishment of a national basic guaranteed income, with others calling for the provision of subsidies for healthy food products. The forthcoming Poverty Reduction Strategy was also seen by many as a potential new way of enhancing food security by improving social programs.

To ensure Canadians have access to safe and nutritious food in a manner that respects their dignity, there were numerous calls throughout consultations for the Government to develop right-to-food legislation in Canada. Some civil society organizations pointed to the fact that the right to food was originally recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 as an acknowledgement that every person should be able to feed themselves in dignity and live in conditions that allow them to either produce or buy food. Many participants also shared the view that a policy founded on the recognition of the right to food for all residents and communities within Canada would commit the nation to a long-term goal of ending, and not merely reducing, food insecurity.

Increasing food security in Indigenous and isolated northern communities

Although food insecurity was seen as an issue with implications for all Canadians, a large number of participants highlighted the particularly high rates of food insecurity in Indigenous and isolated northern communities as an area for immediate action. Participants said that many of the factors that result in higher rates of food insecurity, including low income and reliance on social assistance, are prevalent in Indigenous and isolated northern communities, making food insecurity a particularly important issue. These factors are made worse by high transportation costs and limited retail competition in these communities, and challenges producing food in a cold climate, which contribute to higher food prices and limited availability of the most nutritious types of food.

Participants indicated that improvements were needed to the Nutrition North Canada program, which aims to reduce the price of nutritious and perishable foods in isolated northern communities by way of a retail subsidy. Some expressed uncertainty as to whether the subsidy was benefitting consumers. Among Inuit participants in particular, there is a view that the program transfers power away from communities to companies that do not prioritize community wellness. Additionally, it was suggested that the program does not address food insecurity effectively, although it was not designed to do so, and may create additional barriers to new entrants to the agriculture and food sectors.

There was widespread recognition among participants of the important role played by community- based food security initiatives, particularly in Indigenous and isolated northern communities. Participants called for more investments in such initiatives as well as: greater support for Indigenous and northern food businesses and co-operatives; revisions to the Nutrition North Canada program to enhance its support for local and country/traditional food production; new investments in transportation, distribution, and storage infrastructure; increased food safety inspection at the retail level; and additional income support.

Supporting local, community-based solutions

Participants emphasized the importance of community-led and community-based approaches to food insecurity for all regions and communities in Canada, including urban areas. Many participants indicated that local residents are best placed to identify their community needs, and referred to specific community-led solutions currently underway across Canada as best practices. These initiatives often have additional benefits, such as hands-on education, and linkages to food literacy and economic development. Participants perceived a need for these solutions to be supported, including through the sharing of best practices with other regions experiencing similar issues.

2. Health and Food Safety

Canadian life expectancy has risen dramatically over the past several decades. However, in the past three decades, obesity rates have tripled and chronic diseases such as type II diabetes and hypertension are appearing at younger ages. The food environment increasingly makes healthy food choices challenging. Poor dietary choices are a primary risk factor for obesity and chronic disease, reducing quality of life and placing a significant burden on the health care system.Footnote 1

Canada has a world-class food safety system. However, it is important to ensure that the system can respond to new and emerging risks, and that consumers have the information and knowledge they need when purchasing, handling, preparing and consuming food. When it comes to foodborne illnesses, about four million Canadians (1 in 8) are affected every year. Food policy consultations confirmed that ensuring food in Canada is safe to eat continues to be a high priority for Canadians.

When asked to identify priorities for improving the health of Canadians, and maintaining food safety, consultation participants identified the following, among others:

- Recognizing food as a key determinant of health;

- Promoting health in Indigenous and northern communities;

- Enhancing food literacy and improving food labelling; and

- Addressing food fraud – the deliberate substitution or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients or packaging, for economic gain.

Recognizing food as a key determinant of health

Many participants in consultations perceived a need to expand and promote the availability of safe and healthy food. "Ensuring that food in Canada is as safe as possible" was chosen as a highest priority (65 per cent) under the health and food safety portion of the online survey followed by "Preventing food products with misleading labels or deliberately altered content from entering the market" (64 per cent), "Making healthier food more available for Canadians" (57 per cent), and then "Preventing and reducing obesity and chronic diseases" (41 per cent).

Attributes often associated with "healthy food" included fresh, accessible, high nutrient-value, culturally- appropriate, minimally-processed, low in sugars and fats, inclusive of seafood, Canadian, local, produced without the use of harmful pesticides or drugs, and sustainable. It was also suggested that health-related terms (e.g. "high quality") should be clearly defined in a way that is understandable. Other terms that need clearer definition or explanation, according to some participants, included sugar-free, green, organic, local, and sustainable.

One suggestion during consultations was to discourage consumption of unhealthy foods through taxation measures with the revenues invested in the production of healthy food and health-related initiatives. Another recommendation was to ensure imported food is held to the same standards as food produced and processed in Canada in order to support health and food safety for people in Canada. Support was expressed for regulatory action to ensure that Canadian standards for production methods, ingredients, and additives of imported food.

A number of participants suggested supporting institutions like schools and hospitals in procuring food from local sources would support local food systems and contribute to food security and health. Supporting the growth of local and regional food production was identified as a priority requiring near-term action. Consultation participants also suggested reviewing regulations and perceived barriers to better support local, small-scale, and sustainable food systems, and include consideration of food accessibility and health objectives in their implementation.

Many also called for improvements to the accuracy and frequency of data collection around the food and nutrient intake of Canadians. Additionally, at the National Food Policy Summit, participants put forward suggestions for a Health Impact Assessment to evaluate the potential effects of government policies and initiatives on nutrition and healthy eating outcomes.

Health and food safety in Indigenous and northern communities

As was heard from many participants, high transportation costs to isolated, northern communities result not only in higher food prices, but also in indirect effects on health and food security. For instance, the high cost of nutritious and perishable foods is considered an obstacle to better health outcomes in these communities, especially for people with specific dietary requirements such as diabetics. As well, some participants conveyed that limited transportation and storage infrastructure can contribute to health risks and food waste (e.g., food may be spoiled before it reaches the shelves of stores). Many calls were made for revising the Nutrition North Canada program to support an improved strategy for northern diet and health.

Some participants called for increased food safety inspections in grocery stores in Indigenous and isolated northern communities. Others viewed food safety regulations, particularly for harvested meat, as obstacles to increasing availability of country/traditional food. Many Indigenous and northern participants conveyed that barriers to the consumption of country/traditional foods negatively affect health outcomes, since these foods may be healthier than other available foods.

Enhancing food literacy and improving food labelling

Food literacy refers to knowledge and skills that can complement other efforts to promote healthy eating by helping people learn about where food comes from, nutrition, and food preparation. A large number of participants made it clear they favour enhancing food literacy in Canada through government and community-led interventions, especially with children and populations with low levels of food literacy. Increased food literacy was also seen by many in Indigenous communities as a vehicle for improved health outcomes. Some participants indicated that food literacy efforts should include providing information about agriculture and where food comes from. As well, for some participants, work on food literacy should not just be about information, but also about integrating food into lifestyles differently. In addition, it was suggested that dietary advice should allow for differences in individual needs.

Health Canada played an active role at the Summit and regional engagement sessions and its representatives spoke about key initiatives of the Healthy Eating Strategy for which there appeared to be strong support. Other suggestions included establishing school nutrition programs and garden boxes, as well as education on food preparation and food waste. In particular, many expressed concern about misunderstandings of best before dates contributing to food waste.

Some concerns were expressed about consumers' difficulties understanding available information. For example, it was pointed out that food labels can be complex and nutrition tools such as Canada's Food Guide are not available in all languages. Many participants, particularly at the regional sessions, said food literacy efforts in Indigenous and northern communities should take into account cultural preferences and practices. For example, some participants called for greater recognition of country/traditional foods in the Food Guide. As well, there was a common view that consumers should have enough information to make informed choices about purchasing foods that aligned with their needs and values (such as environmental stewardship, place of origin for seafood, and vegetarianism).

A number of participants wanted to see support for children, youth, and families by developing a national school nutrition program as a component of a food policy. Some also suggested working with Indigenous Representative Organizations to establish this type of program within First Nation reserves. Others wanted to see a larger strategy to address health and food safety education across the population.

Repeatedly, participants sought clarity and transparency on information about the food available in Canada, as well as improved regulations. There were many calls in the consultations for: labelling that can be easily understood; new standards and definitions for accurate labelling (e.g., hormone-free, free-range, antibiotic-free, humane, point of origin for seafood, 'made in Canada', genetically modified information, etc.); improved standards for health and quality for domestic and imported products; and new training for consumers, and producers on health and food safety.

Labelling concerns were also raised in connection with the fishing industry. Participants requested that labelling of fish and seafood products, both domestic and imported, include information such as the common name, scientific name, the location and method of harvest, and facts about nutrition and safety.

Addressing food fraud

Food fraud has emerged as an international issue since global food manufacturing supply chains have grown more complex. Food fraud is the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition, tampering or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients or food packaging for economic gain. This includes adulterating or misrepresenting a food's ingredients to increase the apparent value of the product, reduce the cost of its production, or circumvent trade rules.

Some stakeholders felt that food fraud posed potential reputational and financial risks to the food industry and a significant public health and financial risk to Canadians. Likewise, food-related illnesses that at one time may have been contained to a small region can now be global in scope as a result of both the varied origins of ingredients in any one product and that product's wide-reaching distribution.

Preventing mislabeled or adultered food from entering the Canadian market was an area of interest for some participants in consultations. During in-person consultations, participants expressed concerns about low-quality food being imported into Canada, and the potential for misrepresentation and health risks, especially if food products are adulterated with allergenic or unsafe ingredients. As well, some participants indicated that food fraud is intended to remain undetected and that consumers often lack awareness of it, so consumer complaints are not a satisfactory measure of the amount of food fraud. It was suggested that current federal capacity to address food fraud is limited and reactive.

3. Environment

Canada's agriculture, fisheries, and food sectors continue to work to understand and address the environmental implications of food produced in Canada.

When asked to identify challenges to and opportunities for improving the environmental sustainability of Canada's food system, stakeholders and Canadians identified the following key priorities, among others:

- Taking a broad approach in protecting the environment and climate;

- Acknowledging the link between protection of the environment and traditional/country foods;

- Increasing education, information-sharing, and innovation to support sustainable practices;

- Coordinating more significant action on reducing food waste; and,

- Ensuring agricultural land preservation.

Taking a broad approach to protecting the environment and addressing climate change

Consultation participants expressed that the preservation of agricultural land and biodiversity were key elements missing in the title of the theme and wanted to see more emphasis on both. The lack of reference to biodiversity was a concern for Indigenous participants, and in particular, among those who noted its importance for hunting and harvesting related to country/traditional food production.

Across consultations and submissions, Canadians and stakeholders expressed a desire to see Canada be a global leader in sustainable food system practices. In fact, 76 per cent of online survey respondents to the question of placing emphasis on subthemes chose "Conserving our natural resources" as a top priority. Water supply and quality management was a key concern for some stakeholders in agriculture and fisheries, with respect to considerations such as nutrient management (manure or fertilizer run-off), pesticide contamination, and irrigation or drainage needs. The suggestion was made that a national water management system that includes research and innovation, knowledge transfer, incentives for improving practices, and monitoring mechanisms, be established.

Canadians and stakeholders also want to see climate action and resilience strategies included as key features of the food policy. Climate change was viewed as a significant issue during the consultations. It was a particular concern for Indigenous communities in the North, where it has impacts on access to hunting and harvesting areas, modes of transportation (e.g., ice roads), and wildlife habitat. Many Indigenous participants expressed interest in increased monitoring of the impacts of climate change. It was also suggested that more attention be paid to emergency planning and preparation for the impacts of flooding and climate change on the food system.

Some participants called for increased scrutiny and scientific analysis of pesticides and the impacts they have on the environment, including water systems, animals, and people. In particular, some suggested a pesticide reduction strategy should be established and continually monitored. Synthetic pesticides were a particular concern for some participants. Others suggested improved regulations on the use of antibiotics and hormones in livestock production.

Healthy soil was another priority that emerged under this theme, with the preservation of soil and soil quality emerging as topics of importance. To address this issue, some participants suggested reducing the use of chemicals, antibiotics and hormones to prevent the contamination of the soil and water sources, with some asking for improved regulations.

Many felt, to create a truly sustainable domestic food system, Canada needs to adopt a more holistic and ecological policy approach to ensure prosperity for farmers, fishers, and ranchers, for generations to come. This approach was described as involving research, innovation, financial incentives, and knowledge transfer, to further develop and strengthen food production and provisioning practices that enhance, rather than deplete, the natural environment.

Participants indicated that such a policy approach would also involve measuring progress on reducing the environmental impact of the various parts of the food system. They feel that there is a need to adopt a collaborative approach to strengthening and sharing data on the food sector's environmental performance.

Acknowledging the link between protection of natural resources, wildlife , and traditional food

Wildlife health was a recurring issue raised throughout consultations, and was seen as being affected by a number of factors, including environmental contamination, climate change, and the spread of parasitic diseases.

Many Indigenous participants saw pesticide use and the impacts of natural resource industries (e.g., mining, forestry, development of hydro dams and pipelines, etc.), as key contributors to the increased presence of environmental contaminants in soil and water, the loss of wildlife habitat, wildlife health issues, and the reduced availability and safety of traditional foods in their communities. Participants called for natural resource management practices that better support the availability of country/ traditional food.

Many participants voiced the need for better recognition of traditional knowledge in efforts to foster sustainable food systems (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous). There were also calls to work with Indigenous communities to resolve land claims and usage issues in order to recognize their leadership in protecting their land and natural resources, and some participants saw links to broader concerns about reconciliation.

Increasing education, information sharing, and innovation to support sustainable practices

Consultation participants and submission contributors expressed a desire to see more educational support and training opportunities for farmers and fishers to transition to more sustainable practices, including through the promotion of beneficial management practices. Some Canadians and stakeholders felt that this should include more support for transition to organic and small-scale agriculture, and for improving the availability of local food. As well, particular emphasis was placed by some participants on the need for training, knowledge transfer, and innovation opportunities specifically in the North.

Participants also identified a need for effective innovation and knowledge transfer at other stages of the food system, and felt that incentives to encourage the adoption of environmentally-sustainable practices by processors and consumers could stimulate progress.

Coordinating more significant action on reducing food waste

Participants across the country viewed food loss and waste as a problem of significant environmental, societal, and economic importance – an issue that is relevant throughout the supply chain and for consumers. Fifty-four percent of respondents to the online survey question addressing the subthemes on this section chose "Reducing the amount of food waste in Canada" as a top priority. Support throughout consultations was evident for the development of a broad, cohesive, strategy for reducing food loss and waste. This strategy would include establishing targets, launching an awareness campaign, measuring food loss and waste, and implementing innovative solutions.

Participants expressed strong concerns about the contribution of food loss and waste to greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn contribute to climate change. Some indicated that success in reducing food loss and waste could help Canada meet its commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, and could contribute to achieving future targets for sustainable production and consumption. While some participants rejected the idea of linking food waste reduction and food security, others suggested that more efficient distribution of food (e.g., the efforts of food rescue organizations) could help to address hunger. Food loss and waste for farms and the food industry was also viewed as a significant economic issue with implications for efficiency, profitability, and public trust.

During consultations it was recognized that positive actions are already underway but they are generally considered to be small-scale and disjointed. There was widespread recognition of the opportunities to achieve more, particularly at the household level, and the potential of the federal government to assume a leadership role in food waste reduction.

Suggestions during the consultations included the following: taxing excess food loss and waste; setting mandatory targets or limits (e.g., restrictions on supermarket waste in France); educating businesses and consumers to help reduce food loss and waste (e.g., improving understanding of best-before and expiry dates on food packages); treating wasted food as a resource (e.g., its use in non-food products); recognizing that redirecting wasted food would not, by itself, adequately address either food insecurity or food waste; and collecting better data on food waste and loss.

Ensuring agricultural land preservation

Some online respondents were concerned with protection of land and bodies of water. Preservation of agricultural land was also an item chosen as a top priority requiring short-term action. Both through engagement and submissions received, it was signalled that agricultural land requires protection and should remain for agricultural activities, as should fish habitats and sustainable fisheries. Many also wanted to see more work with Indigenous communities to resolve land claims and usage issues in order to recognize their leadership in protecting the land and natural resources.

4. Economic Growth

Canadian farmers, ranchers, fishers, and food processors have the potential to produce even more high-quality food to meet a growing world demand. Canada's agriculture and food sectors are important drivers of economic growthFootnote 2. Some stakeholders discussed how the policy should align with the Government's ambitious growth agenda for the agri-food sector, including meeting the export target of $75 billion by 2025.

When asked to identify priorities for future growth in the agriculture and food sectors, stakeholders and Canadians identified the following, among others:

- Supporting sector growth and prosperity, including small- and medium-sized operations;

- Promoting innovation, to address existing barriers and adapt to changing market conditions and demands;

- Supporting new entrants to the agriculture and food sectors, with a focus on underrepresented groups;

- Increasing economic growth, competitiveness, and market access;

- Supporting economic growth in Indigenous and northern isolated communities; and

- Balancing economic growth with environmental and other priorities.

Supporting sector growth and prosperity at the local and regional levels, including small- and medium-sized operations

In consultations, the future prosperity of the food system was widely viewed as requiring investment in local and regional food systems. Many participants said the policy should acknowledge a more sustainable, food system that is supported by local, regional, and organic food production. A common recommendation throughout consultations was for public institutions, such as schools and hospitals, to buy a minimum level of food produced locally or regionally as a way to support local economies and promote health.

A shared perspective was that policies enabling small and medium-scale farmers, fishers, processors and retailers to thrive would stimulate economic growth and contribute to a more sustainable, adaptable, and resilient food system for the long term . Participants called for additional support for small-scale farms, including financial support, training and mentorship programs. Support for urban farming, local and farmers' markets, and community gardens was also recommended throughout consultations.

Promoting innovation, to address existing barriers and adapt to changing market conditions and demands

Innovation was viewed as crucial to the success of the food system. During consultations, participants called for increased support for social, environmental, and technological innovation to encourage further progress on food-related issues. Comments from some participants in the consultations highlighted the importance of innovation for the economic growth of the agriculture and food sector and the success of individual businesses. As well, however, some participants noted that innovation has different meanings to different people.

There was broad support for increased investment in social innovations and infrastructure, such as community greenhouses, regional food hubs, and mobile processing units for traditional and country foods, to help local and regional economies flourish.

Participants also perceived a need for local and community-led projects to encourage innovative solutions and sharing of best practices in support of the objectives of the food policy, including investments in isolated northern and Indigenous communities to support successful and sustainable production and harvesting practices.

Supporting new entrants, with a focus on underrepresented groups

Concerns about barriers for new and young entrants in agriculture, wild capture fisheries, and aquaculture (e.g., access to capital, farmland, funding for assets, etc.), and their long-term impact on the sustainability of Canada's food system, were raised repeatedly throughout consultations. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of supporting new entrants into the agriculture and food sectors, particularly groups such as youth, women and Indigenous peoples. The need for increased training and education for new entrants was also identified.

Participants recognized Canada's agriculture, food, fisheries, and aquaculture industries' strong potential for inclusive growth and see it as creating opportunities for a wide range of Canadians. They highlighted the need to develop and implement a collaborative strategy to ensure policies and programs are inclusive, open to all ages, at varying scales of operation, and of different types.

Increasing sector growth, competitiveness, and market access

We heard some calls during the consultations for a greater emphasis on domestic markets, including local initiatives. We also noted participants' recognition of the export-oriented nature of many parts of the food industry in Canada and their mentions of the Government of Canada's objective of reaching $75 billion in agricultural and food exports by 2025.

Participants noted the importance of the agriculture and food sectors to economic growth and job creation. They called for placing a priority on supporting competitiveness, including addressing labour shortages, greater policy and regulatory alignment among federal and provincial governments, and harmonization with international trading partners. Participants emphasized recognition of sustainability efforts underway in Canada and noted that achieving economies of scale helps to make food more affordable. The importance of trade agreements, improved market access, and Canada's representation abroad were among the specific topics identified. There was also interest expressed in aiming to develop more value-added products.

Some participants expressed concerns about what they considered over-regulation, and a need to avoid regulation in areas where industry is already taking effective action.

Growth and self-sufficiency for Indigenous and isolated northern food systems

Greater support for local food production in Indigenous and isolated northern communities was seen by many consultation participants as a solution to food system issues in these communities. Throughout consultations, participants emphasized the importance of acknowledging the role of hunting, harvesting, and fishing as key food provisioning activities in these communities. They called on the Government to address issues that limit the production, distribution, retail, and consumption of country/traditional food such as the high costs of harvesting supplies and equipment, restrictive wildlife quotas, and the impact of climate change and natural resource extraction activities. Food safety inspection regulations, in particular, were seen as creating regulatory barriers to the distribution and sale of country/traditional foods to retail, restaurant, and institutional markets, with negative impacts on economic growth, health, and food security.

Indigenous participants expressed significant interest in becoming more involved in the agriculture and agri-food sectors, with the intent of fostering greater food self-sufficiency and promoting economic development. For example, some Indigenous women saw greater involvement in the food industry as a way of passing on traditional women's practices and teachings. Many obstacles were identified to entry into the sectors, including prohibitive start-up costs, limited access to capital, lack of mentorship and training opportunities, inadequate infrastructure, and difficulty qualifying for programs and policies that do not accommodate different types and scales of operations (e.g., hobby farmers, co-operatives, community-owned processing facilities, etc.). Many called for additional support broad and inclusive enough to address the unique challenges and opportunities faced by these communities.

Balancing economic growth with environmental and other priorities

Some participants in the consultations emphasized the importance of balancing economic and environmental priorities, as well as increased recognition of the interests of smaller and medium-sized businesses. Additionally, it was recommended by some participants that the theme "Growing more high-quality food" be closely linked with the other proposed themes, taking into consideration, for example, environmental sustainability, nutrition, food safety, support for new farmers, labour rights, and animal welfare. It was also suggested that Canada's fisheries and aquaculture sectors require a similar approach to ensure that fish habitats remain sustainable and viable.

In addition to encouraging economic growth, some participants conveyed their view that it is appropriate for governments to encourage best practices in environmental sustainability and resilience to climate change, and provide support for new farmers and organic transition.

Some input received indicated that sustainable growth helps to build public trust of the agriculture and food industry.

In separate consultations on the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, the agriculture and food sector also indicated that building public trust should be a key focus in the next agricultural framework. The sector noted that: while public trust is slow to build, it can be eroded very quickly; consumer education and awareness activities are critical to building public trust; and programming should be reflective of this important need.

Priorities cutting across and interconnecting multiple themes

During the course of consultations, some priorities emerged that cut across themes and stood on their own as important to the success and progress of A Food Policy for Canada:

- The establishment of new governance bodies;

- Policy and program coherence;

- Access to improved data; and

- Distinctions-based approaches to Indigenous food policy.

Governance

Taking into consideration the interconnected nature of the food policy, and the desire to achieve longer-term goals, participants indicated their strong support for establishing an effective governance mechanism that includes coordination with all levels and orders of government. A number of organizations have jointly proposed the creation of an external advisory body with representatives from industry, civil society, government, academia, and Indigenous organizations. This body would provide advice, monitoring, and stakeholder support for the food policy. In addition, participants made suggestions about providing for representation of scientists and philanthropic organizations on an advisory body. Improved inter-departmental coordination across the federal government was also advocated, along with federal-provincial-territorial leadership and coordination.

Food stakeholders noted that an external advisory body would improve coordination across departments and levels of government, and address a perceived lack of inclusivity in policy making related to food. According to some stakeholders, these two issues limit policy coherence and effective action, and contribute to a disconnect between Canada's food producers and the broader Canadian public. It was proposed that an appropriate governance mechanism could help increase confidence and public trust in the food system.

Participants suggested a governance mechanism that could help to:

- align the purpose and objectives of different policies and programs concerning food;

- provide independent advice to government through inclusive engagement;

- share information from different fields and disciplines;

- build public support for policy goals and brokering consensus among diverse stakeholders;

- undertake independent research and monitoring that provides valuable data to assist with policy development;

- identify and target data gaps and set benchmarks to monitor progress; and,

- support continued dialogue, particularly on longer-term issues.

On the composition of an external advisory body, there were strong views that it should be inclusive, and reflect the diversity of Canada's food system. Several stakeholders specifically recommended the establishment of a National Food Policy Council.

Policy and program coherence

A need for policy and program coherence was repeated as a priority in all consultations and themes. For example, under health and food safety, Canadians and stakeholders wanted to ensure policy coherence among the Healthy Eating Strategy, Canadian Food Inspection Agency labelling initiatives, A Food Policy for Canada, and other health and food regulations. Under food security, participants identified a need for coherence among programs that affect poverty reduction, income security, and subsidies (e.g., Nutrition North). Participants noted that recognizing existing food initiatives as part of the policy allows for analysis of gaps and vulnerabilities in policies and programs, and would help to reduce the potential for duplication.

Many participants spoke about the interconnectedness of food policy issues, and the need to take a systems-based approach to addressing food issues to fill gaps, inconsistencies and duplication in policy and programming approaches. There is an impression that the federal government's current approach divides health, environment, agriculture, social development and economic growth into distinct silos. Participants said a systems approach would help to identify integrated solutions across the food system. For example, many said there is a need to ensure that international trade and investment aligns with public programs that enhance respect for human rights, sustainable livelihoods and food sovereignty. Many also felt that best practices in environmental sustainability and climate resiliency should be considered at the same time as policies around economic growth. As well, it was suggested that there are tensions among environmental objectives and goals for increasing food production and exports.

Data collection

Improved collection, sharing, and analysis of food policy data across the food system – and all four themes of the food policy – emerged as a high priority during consultations. Participants broadly identified the need for an approach to data which is open and transparent, and would generate measurable outcomes, encourage public engagement, and strengthen decision-making. It was noted that the existing approach to food data collection, analysis, and dissemination is not well-suited for monitoring and reporting on the food policy.

Key data issues raised included a lack of consistent food policy relevant data, and the need for food system stakeholders to share data and information. For example, the voluntary nature of provincial participation in the Household Food Security Survey Module of the Canadian Community Health Survey was viewed as a key weakness of food insecurity data in Canada because it results in a patchwork of inconsistent data. There were also calls for improved data in other areas, including food waste and health.

Some participants proposed the establishment of specific metrics and suitable targets. Others suggested a central data resource to fulfill the demand for access to high-quality, timely data and information, to facilitate food analytics and research with improved data collation, collection, aggregation, analysis, and dissemination.

Distinctions-based approach

A distinctions-based approach recognizes that First Nations, the Métis Nation, and Inuit, as the Indigenous peoples of Canada, consist of distinct, rights-bearing communities with their own histories. As Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants pointed out during consultations, Indigenous communities in Canada have a unique relationship to food, that is characterized by a strong link between food and cultural identity; unique treaty and constitutional rights; and a history of government interventions in Indigenous communities, lands, and traditional food practices. Even among Indigenous peoples, factors such as gender and age can lead to varied experiences and relationships with food. Indigenous women, for example, have an important role to play in transmitting cultural teachings and knowledge on how to prepare traditional foods to new generations.

In particular, Indigenous participants noted that international agreements, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, call on countries to support the Indigenous right to self-determination. They also noted that Aboriginal and treaty rights, such as the right to hunting and fishing, are recognized and affirmed in the Canadian constitution.

Throughout consultations there were calls for continued nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, and government- to-government discussions between the federal government and First Nations, Inuit and Métis on food policy. This was in recognition of the potential role that the food policy can have in advancing reconciliation, and the understanding that Indigenous communities are best positioned to articulate the food-related issues and challenges they face, and to implement potential solutions for their communities.

For many participants, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, this relationship was seen as extending beyond inclusion of Indigenous representatives on an external advisory body. Rather it would represent a partnership between Government and Indigenous communities, with opportunities for co-development and implementation of policies that impact their respective food systems. Participants at the AFN engagement session emphasized that in order for Indigenous sovereignty to be respected, Indigenous communities and organizations would need to be given decision-making capacity. A distinctions-based approach was recommended during the ITK session that would allow for the creation of an Indigenous food policy, or separate and distinct policies/strategies for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Annexes

Annex A

Details of consultations

Extensive consultation activities were designed to gather Canadians' views on key components of A Food Policy for Canada, namely:

- a vision to set out the policy's long-term aspirations and direction;

- guiding principles to guide its implementation;

- four proposed themes to identify priorities: food security, health and food safety, environment, and economic growth;

- thematic and cross-cutting priorities;

- measurable objectives to help advance progress towards meeting the policy's economic, social, health, and environmental goals;

- possible short-term actions to further operationalize the framework beyond existing programs; and

- how best to enable ongoing dialogue on food policy.

As engagement progressed, discussions in each of these areas evolved to reflect what was heard in previous discussions.

Participants were provided with documentation in support of consultations to ensure they had a similar understanding of the expectations for the policy and the issues it is intended to address. Documentation included a placemat highlighting the four possible themes for the food policy. To review, the themes are described in greater detail below:

Increasing access to affordable food

Improving Canadians' access to affordable, nutritious, and safe food.

Not all Canadians have sufficient access to affordable, nutritious and safe food. We need to do more to improve the affordability and availability of food, particularly among more vulnerable groups, such as children, Canadians living in poverty, Indigenous peoples, and those in remote and Northern communities.

Improving health and food safety

Increasing Canadians' ability to make healthy and safe food choices.

Canada's world class food safety system continues to provide its citizens with safe food to eat. Additional efforts to promote healthy living through nutritious and safe food choices, can improve the overall health of Canadians, while lowering health care costs.

Conserving our soil, water, and air

Using environmentally sustainable practices to ensure Canadians have a long-term, reliable, and abundant supply of food.

The way our food is produced, processed, distributed, and consumed - including the losses and waste of food - can have environmental implications, such as greenhouse gas emissions, soil degradation, water quality and availability, and wildlife loss. While much is being done to conserve our natural resources, further opportunities exist to do more.

Growing more high-quality food

Ensuring Canadian farmers and food processors are able to adapt to changing conditions to provide more safe and healthy food to consumers in Canada and around the world.

Enabling farmers and food processors, large and small, across the country, to grow, will make more high-quality Canadian food available domestically and internationally. Budget 2017 investments clearly recognize the importance of the agriculture and food sector as a driver of economic growth.

Participants of government-led consultations were also provided with fact sheets offering a diagnostique for each of the theme areas (Annex C), as well as background information and some key statistics. In the documents, as well as all other consultations documentation, the four proposed themes were framed as: increasing access to affordable food; improving health and food safety; conserving our soil, water and air; and growing more high-quality food.

These themes represent interrelated policy areas, and were used throughout consultations to focus discussions in the key areas of food security; health; environmental sustainability; and growth of the agriculture and food sectors. These four areas were based on earlier policy proposals published by key stakeholder groups in Canada, as well as food policy efforts in other countries, as encompassing the themes on which a policy should be established. There was strong support throughout the engagement process for building a food policy based on the four proposed themes.

Online Survey

The online survey was open between May 29th and August 31st, 2017. To help raise awareness of the survey and increase participation, it was promoted through Facebook and other social media like Twitter and Instagram, up until the end of August 2017. As the survey was completed by self-selected Canadians, these results cannot be generalized to all Canadians. However, given its significant sample size (there were close to 45,000 responses), it does provide some depth of insight into Canadians' perceptions and priorities on issues related to food.

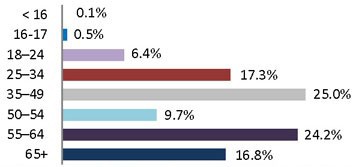

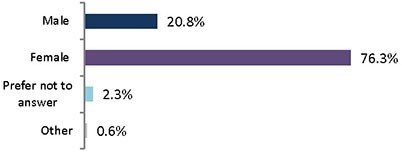

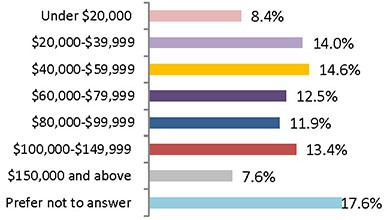

The format of the survey allowed the Government to gather valuable input: multiple choice questions asked respondents to rank principles and priorities under the four themes to give a general sense of Canadians' food-related priorities, while qualitative questions allowed for more in-depth and personalized feedback on what respondents wanted to see in the food policy. As well, demographic questions about age, gender, personal identification (ethnicity, disability), occupation, income, language and geographic location (remote vs. urban), allowed the Government to capture demographic and regional differences (see graphic representation below).

Overview of Online Survey Respondent Demographics

Figure 1. Age (44,068 responses)

Description of Figure 1

| Age | % |

|---|---|

| < 16 | 0.1 |

| 16-17 | 0.5 |

| 18–24 | 6.4 |

| 25–34 | 17.3 |

| 35–49 | 25 |

| 50–54 | 9.7 |

| 55–64 | 24.2 |

| 65+ | 16.8 |

Figure 2. Gender (43,619 responses)

Description of Figure 2

| Gender | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 20.8 |

| Female | 76.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2.3 |

| Other | 0.6 |

Figure 3. Household income (24,177 responses)

Description of Figure 3

| income | % |

|---|---|

| Under $20,000 | 8.4 |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 14 |

| $40,000-$59,999 | 14.6 |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 12.5 |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 11.9 |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 13.4 |

| $150,000 and above | 7.6 |

| Prefer not to answer | 17.6 |

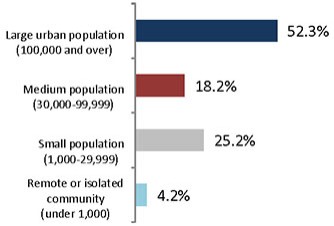

Figure 4. Size of respondents' community (# of people) (24,125 responses)

Description of Figure 4

| Size | % |

|---|---|

| Large urban population (100,000 and over) |

52.3 |

| Medium population (30,000-99,999) |

18.2 |

| Small population (1,000-29,999) |

25.2 |

| Remote or isolated community (under 1,000) |

4.2 |

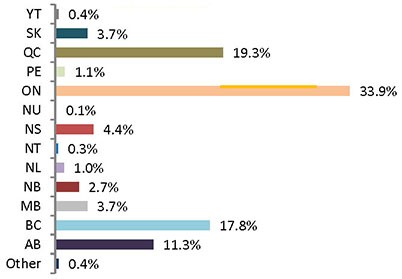

Figure 5. Location (43,631 responses)

Description of Figure 5

| Location | % |

|---|---|

| YT | 0.4 |

| SK | 3.7 |

| QC | 19.3 |

| PE | 1.1 |

| ON | 33.9 |

| NU | 0.1 |

| NS | 4.4 |

| NT | 0.3 |

| NL | 1 |

| NB | 2.7 |

| MB | 3.7 |

| BC | 17.8 |

| AB | 11.3 |

| Other | 0.4 |

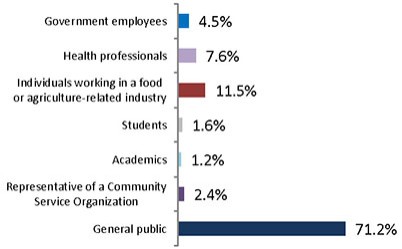

Figure 6. Background of respondents (43,552 responses)

Description of Figure 6

| Background of Respondents | % |

|---|---|

| Government employees | 4.5 |

| Health professionals | 7.6 |

| Individuals working in a food or agriculture-related industry | 11.5 |

| Students | 1.6 |

| Academics | 1.2 |

| Representative of a Community Service Organization | 2.4 |

| General public | 71.2 |

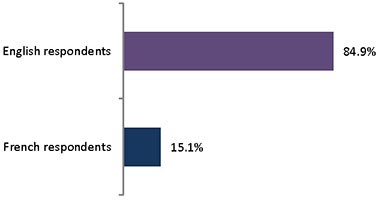

Figure 7. Language (40,224 responses)

Description of Figure 7

| Language | % |

|---|---|

| English respondents | 84.9 |

| French respondents | 15.1 |

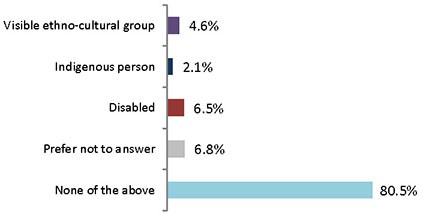

Figure 8. Minority groups (43,617 responses)

Description of Figure 8

| Group | % |

|---|---|

| Visible ethno-cultural group | 4.6 |

| Indigenous person | 2.1 |

| Disabled | 6.5 |

| Prefer not to answer | 6.8 |

| None of the above | 80.5 |