Author: Steve Javorek

Summary

Canada's diverse agricultural landscape provides habitat for close to 550 species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. Although these agro-ecosystems support many of Canada's native wildlife species, shifting economic factors drive dynamic land-use change which can have both beneficial and detrimental impacts on wildlife.

Agriculture can have positive effects on wildlife by increasing landscape heterogeneity, or it can have negative effects through the loss, alteration or fragmentation of habitat. The vast majority of wildlife species (close to 72%) associated with agricultural land depend upon natural or semi-natural land-cover types, such as woodlands, wetlands or managed grasslands, to provide primary breeding and feeding habitat. In sharp contrast, just under 3% of identified wildlife species could fulfill both breeding and feeding requirements on annual cropland alone. Consequently, the existence of viable wildlife populations on farmland is tied to the availability of natural and semi-natural cover types within the Canadian agricultural landscape. The Potential Wildlife Habitat Capacity (WHC) on Farmland Indicator assesses the overall state and trend of the Canadian agricultural landscape from the standpoint of the availability of suitable habitat for populations of terrestrial vertebrates.

In 2015, the largest proportion of land in the Canadian agricultural extent was classified as having High Wildlife Habitat Capacity for reproduction (37.43%) followed by Very Low (24.15%), Moderate (14.45%), Low (12.74%) and Very High (11.23%). For wildlife habitat capacity for feeding, the largest proportion of land was classified High (45.67%), followed by Moderate (21.77%), Low (21.01%), Very High (11.53%) and Very Low (0.02%). From 2000-2015, national wildlife habitat capacity for reproduction was Stable on 74.71% of land, Declined on 24.73% and Increased on 0.57%, resulting in an overall rate of Decline of −0.08%/year. Feeding wildlife habitat capacity was Stable on 84.70% of land within the agricultural extent, Declined on 15.17% and Increased on 0.12% with an overall rate of Decline of −0.06%/year. Drivers of wildlife habitat capacity change differ by region, including loss of grasslands, wetlands and other natural or semi-natural cover, expansion of annual cropland and urban areas, and loss of perennial cropland.

The issue and why it matters

Approximately 8% of Canada's landmass is used for agriculture; this land is comprised of cultivated lands, hay lands and grazing lands, as well as associated natural and semi-natural cover types such as wetlands, woodlands, riparian areas and grasslands. There are 545 identified species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians that use this mosaic of land cover for feeding, breeding or shelter. Each of these species has unique habitat requirements which must be satisfied in order for viable populations to exist.

Although agricultural landscapes can support many of Canada's native species, agricultural land use is dynamic and changes can have major impacts on wildlife. Over time, land clearing to develop cropland or pastures has reduced the amount of natural habitat in many regions. Wildlife habitat on farmland is degraded through the conversion of natural and semi-natural areas to cropland, increased use of chemical inputs, drainage of wetlands, removal of windbreaks and natural field barriers to accommodate larger machinery, and sometimes through an increase in livestock density. These changes can lead to habitat fragmentation and the overall loss of landscape heterogeneity.

Since a large percentage of the terrestrial area within some ecozones of Canada (for example, the Prairies) is devoted to agricultural use, planning is essential at the provincial or national level to accommodate the needs of a wide range of species found in these areas and to support the management of Canada's biodiversity. Conservation and enhancement of wildlife habitat in agricultural areas is particularly important, since some of the species that use farmland as habitat are classified as at risk (Wild Species Report, 2015; Javorek and Grant, unpublished data) under provincial and/or federal species at risk legislation. This classification may lead to increased public or regulatory pressure on producers to alter their management practices in order to protect and conserve these habitats on their farms. Currently, half of the terrestrial vertebrates listed as at risk in Canada use farmland within part of or across their feeding and breeding ranges. The Migratory Birds Convention, a treaty signed with the United States to protect migratory birds, can also have implications for the management of agricultural lands.

Agriculture benefits from the important ecosystem services provided by wildlife, including crop pollination and natural pest control. The provision of wildlife habitat in agricultural regions, through the creation or maintenance of buffers, woodlots or wetlands, for example, also provides other benefits such as improved soil and water quality, efficient nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration. Nonetheless, public efforts to conserve and restore habitat capacity on private lands must consider the realities of the working landscape, including production and economic factors in the agricultural sector. Several initiatives exist (administered both provincially as well as through non-governmental funding sources) to compensate farmers for the provision or enhancement of ecosystem services in targeted areas that contribute to the public good.

Canada's ability to report on trends in biodiversity and interactions with agricultural production is an essential part of demonstrating the environmental sustainability of the agriculture and agri-food system, with implications for domestic and international commitments, as well as for maintaining public trust in the sector. This indicator is a meaningful proxy for the state and trend of biodiversity in agricultural landscapes and can also help to identify opportunities for the sector to make improvements. Of note, Canada has used this indicator for past reporting to the Convention on Biological Diversity in order to report on progress towards domestic and international biodiversity goals.

The indicator

The Potential Wildlife Habitat Capacity on Farmland Indicator provides a multi-species assessment of broad-scale trends in the capacity of the Canadian agricultural landscape to provide potential reproductive and feeding habitat for populations of terrestrial vertebrates.

The WHC of the Canadian agricultural landscape was investigated from 2000 to 2015 at five-year intervals to coincide with the AAFC Semi-Decadal Land Use Time Series earth-observation dataset, which is the source of land-cover data used for indicator calculation in conjunction with the Earth-Observation-adjusted Census of Agriculture. The analysis was restricted to the Soil Landscape of Canada polygons that are reported on in the census, which ultimately identifies areas deemed agricultural or influenced by agricultural activities.

Wildlife Habitat on Farmland performance index

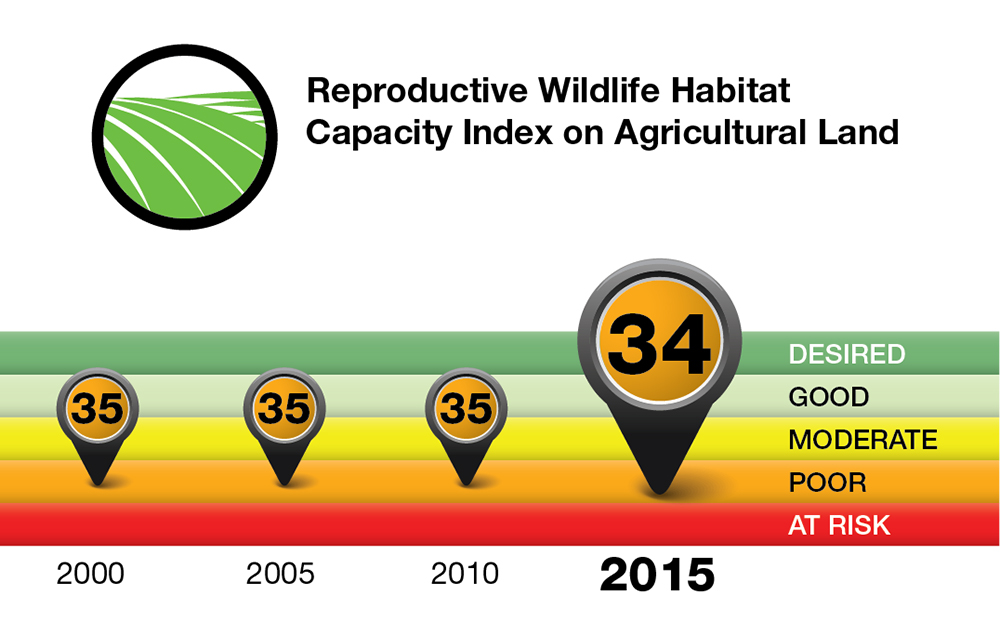

The state and trend of the Reproductive Wildlife Habitat on Farmland Indicator can be seen in the performance index.

Description of image the above

Reproductive Wildlife Habitat Capacity Index on Agricultural Land logo.

The Potential Wildlife Habitat Capacity on Farmland Indicator covers the years 2000 to 2015 in five-year increments. The index value ranges from 0 to 100 in twenty-point increments with each increment assigned a qualitative rating: 0-19 is At risk; 20-39 is Poor; 40-59 is Moderate; 60-79 is Good; 80-100 is Desired.

| Year | Index Value | Index rating |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 35 | Poor |

| 2005 | 35 | Poor |

| 2010 | 35 | Poor |

| 2015 | 34 | Poor |

When viewed at a national scale using a single index value for the whole country, overall reproductive wildlife habitat capacity on farmland has not changed significantly between 2000 and 2015. The index tends to aggregate and generalize trends and so should be viewed as a policy tool to give a general overview of state and trend over time.

It is important to recognize that a desired level of habitat capability is likely unattainable on annual cropland. While some species find cropland good for feeding, fewer species can use it for reproduction because of the disruption of cultivation, seeding and harvest.

Methodology

Reporting area and time frame

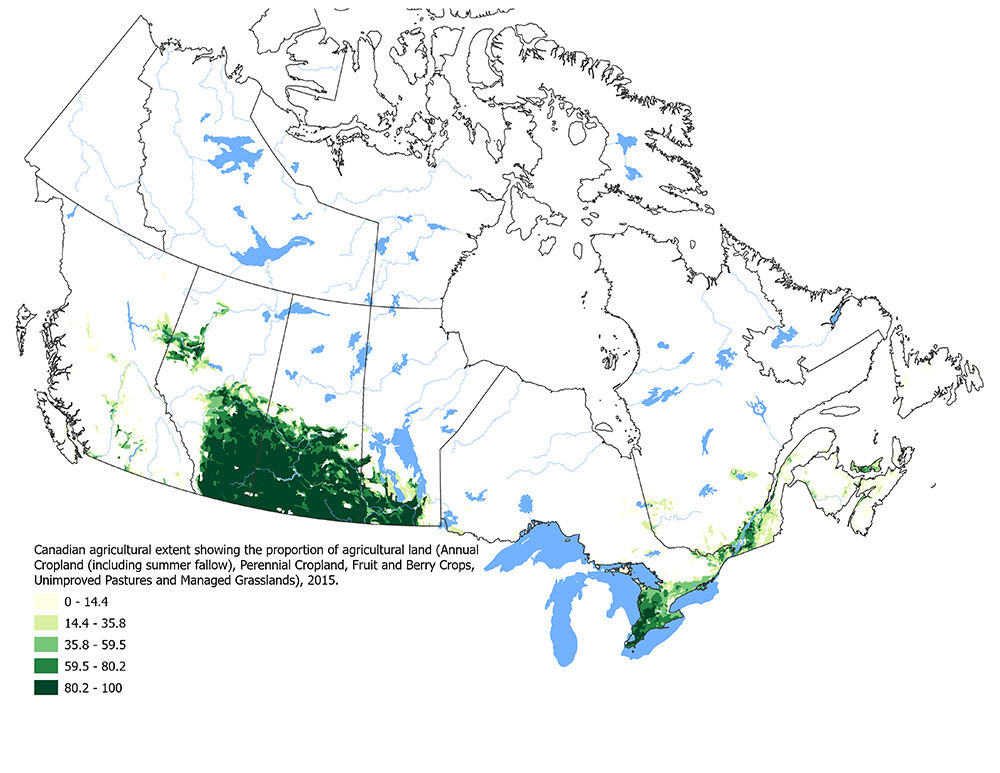

Potential Wildlife Habitat Capacity was determined for the agricultural extent of Canada (AAFC and Statistics Canada, Earth Observation Adjusted Interpolated Census of Agriculture Canadian Agricultural Extent)(figure 1) at five year intervals from 2000-2015. All analyses were done at the Soil Landscapes of Canada Polygons (SLC) v3.2 level, then rolled up for National and Provincial State and Trend reporting.

Description of Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates the Canadian agricultural extent showing the proportion of agricultural land (annual cropland (including summer fallow), perennial cropland, fruit and berry crops, unimproved pastures and managed grasslands, color coded based on the proportion of agricultural land.

Wildlife

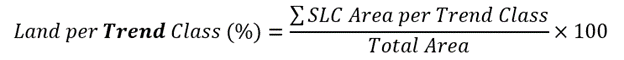

A habitat association matrix was constructed for 545 terrestrial vertebrates (332 birds, 134 mammals, 41 amphibians and 38 reptiles) that use land cover within the agricultural extent of Canada for reproduction and/or feeding. Each cover type (used as a synonym for habitat in this report) used by wildlife species was identified as Primary (always used, critical or strongly preferred habitat), Secondary (often used, important habitat) or Tertiary (occasionally used, low value habitat) with values of 1.0, 0.75 and 0.25 assigned, respectively, to reflect the relative importance of the land cover for both reproduction and feeding. Habitat association matrices were spatially linked to land cover information within the agricultural extent by rectifying species breeding distribution data to the SLC level.

Land cover

Land cover information was obtained from (1) AAFC Earth Observation Semi-Decadal Land Use Time Series Product (SDLU, 30 metre resolution)(official name/ref) and (2) the AAFC Earth Observation Adjusted Census of Agriculture (EOCOA, SLC resolution) (official ref). Cover types included in the SDLU were Settlement, Vegetated Settlement, Cropland, Managed Grassland, Woodland, Woodland Regeneration (following harvest), Woodland Regeneration (following fire), Wooded Wetland, Wetland, Water, and Other Land. The EOCOA was used to differentiate agricultural cover types at the SLC-level within the area of SDLU Cropland. These included Annual Cropland (including Summerfallow), Perennial Cropland, Fruits and Berries and Unimproved Pasture.

Wildlife habitat capacity calculation

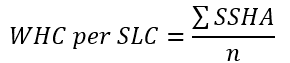

Initially, species-specific habitat availability (SSHA) for reproduction and feeding was calculated at the SLC level as follows:

where; CT% is the proportion of the cover type used by a species in the SLC and HUV is the habitat use value (Primary=1, Secondary=0.75 and Tertiary=0.25).

Next, Wildlife Habitat Capacity for reproduction (WHCR) and for feeding (WHCF) were calculated for each SLC as:

Where n is the number of species per SLC.

Finally, National and Provincial WHC index values were determined as the average WHCR and WHCF among SLCs within the desired reporting unit.

Wildlife habitat capacity (state)

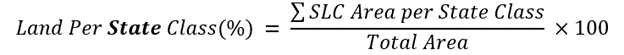

The National range of WHCRF/SLC scores was divided equally into five State Classes: Very Low (4.72 – 17.27), Low (17.27 - 29.82), Moderate (29.82 - 42.37), High (42.37 - 54.92) and Very High (54.92 - 67.47). The proportion of land within each State Class was calculated as:

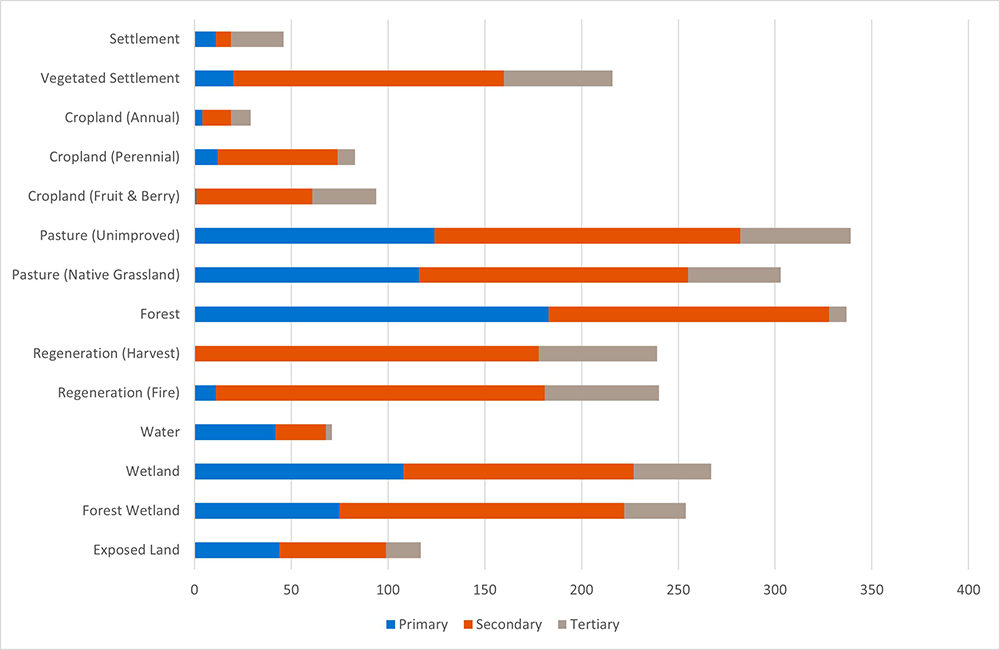

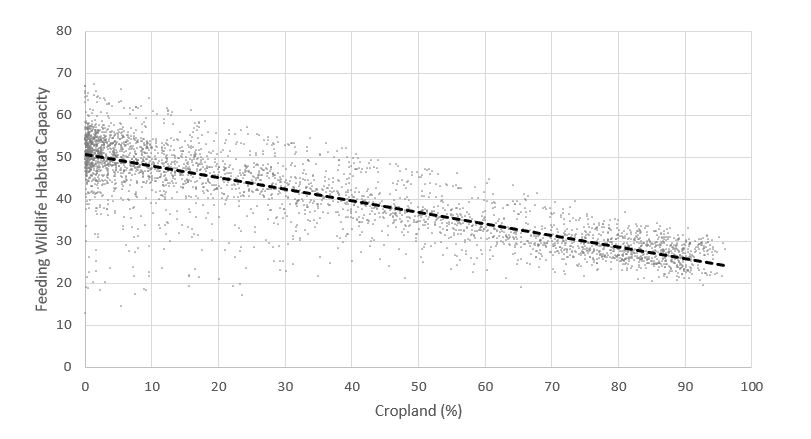

Wildlife habitat capacity (trend)

Trend was established as the slope of the linear trendline fit through WHCR and WHCF scores across 15 years expressed as percent habitat capacity change per/year. Five Trend categories were established based on change rates of 0.1%/year: Stable/Slight Change (Δ HC 0.1 to -0.1%/year), Moderate Increase (Δ HC 0.1 to0.3/year), Large Increase (Δ HC >0.3/year), Moderate Decrease (Δ HC -0.1 to -0.3/year) and Large Decrease (Δ HC <-0.3/year). The proportion of land within each Trend category was calculated as:

Limitations

The WHC Indicator deals only with the broad-scale quantity of habitat and does not address the influence of finer-resolution micro-habitat or landscape configuration (for example, landscape heterogeneity or fragmentation) on wildlife.

Agricultural landscapes are dynamic, with beneficial and detrimental land-cover changes often happening concurrently. Analyses conducted at broad national or provincial scales can lead to a counterbalancing of the effects of land-cover change on wildlife, and mask habitat changes at regional or local scales. Therefore, it is important to interpret the trends carefully, since relatively small local changes in natural and semi-natural land cover, which are not captured with broad-scale assessment, can have a major impact on wildlife.

It should be kept in mind that wildlife populations are opportunistic and adaptive. The indicator does not currently relate changes in wildlife habitat capacity to the responses of wildlife populations.

The WHC category rankings are based on their relative value among all reporting SLC polygons, and not on biologically derived habitat classification rankings. The indicator currently looks at all land considered within the agricultural extent in Canada (see above) and therefore incorporates the influence of other adjacent land use types (for example, forestry) on wildlife.

National results and interpretation

Wildlife

Nationally, there are 545 species of terrestrial vertebrates (332 birds, 134 mammals, 41 amphibians and 38 reptiles) that use land within the agricultural extent in Canada for reproduction and feeding. According to the 2015 General Status of Species in Canada breeding ranks, 419 species (76.88%) are listed as secure or apparently secure, 64 (11.74%) vulnerable, 23 (4.22%) imperiled and 19 (3.49%) critically imperiled. Twenty species evaluated for the Wildlife Habitat Capacity Index were not assessed in the 2015 General Status Report.

Figures 2 and 3 show the number of terrestrial vertebrate species associated with each land cover type in the Canadian agricultural extent and whether it provided primary, secondary or tertiary habitat for breeding and feeding purposes, respectively. Natural and semi-natural land (Woodland, Wooded Wetland, Wetland, Water, Managed Grassland and Unimproved Pasture) provided primary breeding and feeding habitat for many species. These cover types are extremely important for wildlife, providing both primary reproductive and feeding habitat for the vast majority of species (71.92%) and met habitat requirements for 93.94% of species when both primary and secondary habitat was considered. Many species used Regenerating Woodland following harvest or fire as secondary/tertiary habitat for reproduction and feeding but it offered little in the way of primary habitat. Cropland cover types were used by relatively few species compared to natural and semi-natural cover types. Only 2.93% of species used Cropland cover types (Annual, Perennial, Fruits and Berries) as primary reproductive habitat which increased to 21.28% when both primary and secondary habitat use was considered. Annual Cropland provided primary reproductive habitat for just 0.73% of species (3.48% of species for primary and secondary habitat) while Perennial cover offered primary habitat to 2.20% of species (13.57% of species for primary and secondary habitat). The inability of Cropland alone to fulfill habitat requirements for the vast majority of wildlife species highlights the importance of natural and semi-natural cover types in Canadian agricultural landscapes.

Description of Figure 2

| Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed Land | 44 | 55 | 18 |

| Forest Wetland | 75 | 147 | 32 |

| Wetland | 108 | 119 | 40 |

| Water | 42 | 26 | 3 |

| Regeneration (Fire) | 11 | 170 | 59 |

| Regeneration (Harvest) | 0 | 178 | 61 |

| Forest | 183 | 145 | 9 |

| Pasture (Native Grassland) | 116 | 139 | 48 |

| Pasture (Unimproved) | 124 | 158 | 57 |

| Cropland (Fruit and Berry) | 1 | 60 | 33 |

| Cropland (Perennial) | 12 | 62 | 9 |

| Cropland (Annual) | 4 | 15 | 10 |

| Vegetated Settlement | 20 | 140 | 56 |

| Settlement | 11 | 8 | 27 |

Description of Figure 3

| Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed Land | 24 | 42 | 12 |

| Forest Wetland | 63 | 177 | 33 |

| Wetland | 108 | 200 | 26 |

| Water | 58 | 68 | 3 |

| Regeneration (Fire) | 11 | 234 | 69 |

| Regeneration (Harvest) | 2 | 240 | 71 |

| Forest | 174 | 154 | 20 |

| Pasture (Native Grassland) | 125 | 181 | 29 |

| Pasture (Unimproved) | 131 | 208 | 44 |

| Cropland (Fruit and Berry) | 3 | 106 | 49 |

| Cropland (Perennial) | 16 | 126 | 25 |

| Cropland (Annual) | 5 | 89 | 44 |

| Vegetated Settlement | 18 | 178 | 59 |

| Settlement | 11 | 13 | 41 |

Land cover

State (2015)

Table 1 shows National and Provincial proportions of each cover type in the agricultural extent in 2015. Agricultural land cover (Annual Cropland, Perennial Cropland, Fruits and Berries, Unimproved Pasture and Managed Grassland) comprised 40.69% of land within the agricultural extent of Canada in 2015. Cropland comprised 34.61% with Annual Cropland (24.46%) around three times that of Perennial Cropland (8.35%). Managed Grassland and Unimproved Pasture comprised 6.07% and 1.68% of land, respectively. Woodland was a major component of many agro-ecosystems comprising 34.90% of land Nationally. Forestry activity (harvest) was a dynamic component of the landscape converting Woodland to Woodland Regeneration on 4.09% of land. Wetlands (Wetland: 5.42%, Wooded Wetland 5.29%) are important habitats for wildlife along with Open Water (4.53%). Nationally, natural or semi-natural land (Woodland, Wetland, Water, Managed Grassland and Unimproved Pasture) comprised 61.75% of land in the agricultural extent. Settlements and Vegetated Settlements made up 0.89 and 0.97% of land, respectively.

Trend (2000-2015)

Table 1 shows the National and Provincial cover type change (%) and share of agricultural land over 15 years. The National agricultural footprint in Canada contracted slightly over 15 years by -0.07%. This trend was not consistent among Provinces with some showing increase (Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland) and others decline (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec). Nationally, land cover changed on 3.11% of the agricultural extent. Over 15 years, the share of Annual Cropland (including Summerfallow) expanded by 0.98% while Perennial Cropland declined by 0.31%. Managed Grassland and Unimproved Pasture declined by 0.55% and 0.21%, respectively. The share of Woodland declined by -1.94% which resulted in a 1.47% increase in the proportion of land under Woodland Regeneration following harvest. Nationally, Wetland and Wooded Wetland declined by -0.03% and -0.06%, respectively. Both Settlements (0.26%) and Vegetated Settlements (0.19%) increased.

| State 2015 (Change 2000-2015) |

Settlement - State % (Change %) |

Roads - State % (Change %) |

Vegetated Settlement - State % (Change %) |

Cropland (Annual) - State % (Change %) |

Cropland (Perennial) - State % (Change %) |

Cropland (Fruit and Berry) - State % (Change %) |

Unimproved Pasture - State % (Change %) |

Managed Grassland - State % (Change %) |

Regeneration (Harvest) - State % (Change %) |

Regeneration (Fire) - State % (Change %) |

Woodland - State % (Change %) |

Wooded Wetland - State % (Change %) |

Unmanaged Grassland - State % (Change %) |

Wetland - State % (Change %) |

Water - State % (Change %) |

Other Land - State % (Change %) |

Agricultural Land Cover - State % (Change %) |

Cover Type Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 1.12 (0.32) |

1.71 (0.03) |

0.71 (0.13) |

28.43 (3.05) |

13.26 (-1.79) |

0 (0) |

1.51 (-0.31) |

13.88 (-1.03) |

1.75 (0.71) |

0.37 (0.11) |

22.98 (-1.11) |

4.84 (-0.07) |

1.16 (-0.01) |

5.7 (-0.05) |

2.47 (0.02) |

0.11 (0) |

57.08 (-0.08) |

4.37 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.28 (0.08) |

1.92 (0) |

0.35 (0.05) |

53.26 (-1.34) |

12.4 (2.74) |

0 (0) |

1 (-0.15) |

11.84 (-1.23) |

0.38 (0.18) |

0.14 (0.08) |

7.02 (-0.28) |

1.67 (-0.1) |

0.49 (0) |

6.24 (-0.03) |

2.94 (0.01) |

0.08 (0) |

78.5 (0.01) |

3.14 |

| Manitoba | 0.34 (0.06) |

1.77 (0.01) |

0.54 (0.16) |

32.17 (1.76) |

8.25 (-1.14) |

0 (0) |

2.03 (-0.23) |

1.39 (-0.51) |

1.33 (0.71) |

0.09 (-0.14) |

22.13 (-0.65) |

5.41 (-0.03) |

1.45 (0) |

13.11 (-0.01) |

10 (0) |

0.01 (0) |

43.83 (-0.12) |

2.71 |

| Ontario | 1.31 (0.28) |

2.11 (0.08) |

1.87 (0.26) |

13.33 (1.76) |

4.14 (-1.71) |

0.1 (-0.02) |

3.8 (-0.2) |

not applicable | 3.51 (0.87) |

0.07 (-0.02) |

44.92 (-1.18) |

13.11 (-0.09) |

0.78 (-0.01) |

4.24 (-0.03) |

6.69 (0) |

0.03 (0) |

21.38 (-0.16) |

3.25 |

| Quebec | 1.07 (0.37) |

1.71 (0.23) |

1.45 (0.26) |

6.82 (0.89) |

4.75 (-0.85) |

0.28 (0.13) |

1.48 (-0.34) |

not applicable | 6.15 (0.87) |

0.15 (0) |

65.51 (-1.5) |

3.11 (-0.01) |

0.48 (-0.02) |

1.78 (-0.01) |

5.24 (-0.01) |

0.02 (-0.01) |

13.33 (-0.17) |

2.75 |

| New Brunswick | 0.87 (0.33) |

1.7 (0.07) |

1.57 (0.45) |

1.8 (0.06) |

2.54 (-0.37) |

0.59 (0.41) |

1.18 (-0.09) |

not applicable | 15.89 (4.92) |

0.05 (-0.09) |

61.22 (-5.75) |

5.38 (0.08) |

0.73 (0) |

3.82 (-0.01) |

2.57 (0) |

0.07 (0) |

6.12 (0.01) |

6.32 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.52 (0.12) |

1.75 (0.02) |

1.84 (0.52) |

0.99 (0.13) |

3.27 (-0.17) |

0.88 (0.13) |

0.3 (-0.03) |

not applicable | 17.14 (6.79) |

0.05 (0.02) |

60.82 (-7.54) |

5.1 (0.03) |

0.7 (0) |

2.14 (-0.02) |

4.38 (0) |

0.12 (0) |

5.44 (0.06) |

7.77 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.53 (0.26) |

3.01 (0.03) |

2.47 (0.71) |

21.43 (1.64) |

11.82 (-0.45) |

1.23 (0.59) |

6.36 (0.68) |

not applicable | 7.23 (3.38) |

0 (0) |

34.18 (-6.65) |

3.51 (-0.12) |

0.92 (0) |

3.61 (-0.03) |

3.6 (-0.03) |

0.1 (0) |

40.83 (2.46) |

7.29 |

| Newfoundland | 0.96 (0.17) |

1.51 (0.04) |

1.33 (0.25) |

0.13 (-0.03) |

0.84 (0.05) |

0.04 (0.02) |

0.01 (-0.01) |

not applicable | 5.87 (1.32) |

0.08 (-0.6) |

63.62 (-1.09) |

6.26 (-0.09) |

2.16 (-0.01) |

9.7 (-0.01) |

7.26 (0) |

0.22 (0) |

1.02 (0.03) |

1.86 |

| Canada | 0.89 (0.26) |

1.76 (0.06) |

0.97 (0.19) |

24.46 (0.98) |

8.35 (-0.31) |

0.12 (0.04) |

1.68 (-0.21) |

6.07 (-0.55) |

4.09 (1.47) |

0.29 (0.13) |

34.9 (-1.94) |

5.29 (-0.06) |

1.04 (-0.01) |

5.42 (-0.03) |

4.53 (0) |

0.12 (0) |

40.69 (-0.07) |

3.11 |

Potential wildlife habitat capacity

State (2015)

Reproduction

In 2015, WHCR varied from Low to High among Provinces resulting in a National rating of Moderate (Table 2). Nationally, the largest proportion of land in the agricultural extent was classified as having High WHCR (37.43%) followed by Very Low (24.15%), Moderate (14.45%), Low (12.74%) and Very High (11.23%). Table 3 shows the proportion of National/Provincial agricultural land in each habitat capacity class and shows the spatial distribution of this information across the agricultural extent of Canada. Lower WHCR was generally associated with agricultural landscapes comprised of higher proportions of Cropland (figure 5). Areas with lower habitat capacity include the Lower Mainland and central river valleys of the Thompson Okanagan Plateau of British Columbia, areas of the Prairies, Manitoulin-Lake Simcoe and Lake Erie Lowland Ecoregions of Ontario, St. Lawrence Lowlands Ecoregion of Quebec and pockets of higher agricultural production in Atlantic Canada including central areas of Prince Edward Island and the Annapolis-Minas Lowlands of NS.

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | %Change/Year 2000-2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 44.41 (H) | 43.58 (H) | 42.51 (H) | 42.19 (H) | -0.16 (SD) |

| Alberta | 32.70 (M) | 32.62 (M) | 32.17 (M) | 31.55 (M) | -0.08 (S) |

| Saskatchewan | 23.44 (L) | 23.76 (L) | 23.39 (L) | 22.88 (L) | -0.04 (S) |

| Manitoba | 26.12 (L) | 26.20 (L) | 25.85 (L) | 25.26 (L) | -0.06 (S) |

| Ontario | 32.12 (M) | 31.89 (M) | 31.49 (M) | 31.24 (M) | -0.06 (S) |

| Quebec | 42.22 (M) | 41.79 (M) | 41.48 (M) | 41.30 (M) | -0.06 (S) |

| New Brunswick | 51.50 (H) | 50.40 (H) | 49.71 (H) | 49.38 (H) | -0.14 (SD) |

| Nova Scotia | 47.03 (H) | 45.71 (H) | 44.75 (H) | 44.76 (H) | -0.16 (SD) |

| Prince Edward Island | 33.96 (M) | 33.55 (M) | 31.91 (M) | 31.79 (M) | -0.16 (SD) |

| Newfoundland | 50.12 (H) | 49.91 (H) | 49.84 (H) | 49.81 (H) | -0.02 (S) |

| Canada | 35.51 (M) | 35.21 (M) | 34.66 (M) | 34.29 (M) | -0.09 (S) |

| Very High | High | Moderate | Low | Very Low | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 2.68 | 74.85 | 16.98 | 4.28 | 1.21 |

| Alberta | 3.59 | 32.20 | 16.15 | 19.38 | 28.68 |

| Saskatchewan | 1.20 | 10.35 | 12.45 | 16.57 | 59.43 |

| Manitoba | 0.00 | 19.75 | 31.61 | 9.45 | 39.19 |

| Ontario | 11.89 | 51.68 | 11.31 | 17.16 | 7.97 |

| Quebec | 23.53 | 55.88 | 9.83 | 6.47 | 4.29 |

| New Brunswick | 17.53 | 75.75 | 6.32 | 0.41 | 0.00 |

| Nova Scotia | 5.97 | 83.42 | 9.12 | 1.27 | 0.21 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.00 | 16.29 | 56.31 | 27.40 | 0.00 |

| Newfoundland | 1.52 | 90.46 | 8.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Canada | 11.23 | 37.43 | 14.45 | 12.74 | 24.15 |

Description of Figure 4

Figure 4 illustrates the spatial distribution of reproductive wildlife habitat capacity among state classes in the Canadian agricultural extent in 2015, color coded based on the capacity level from very low to very high.

Feeding

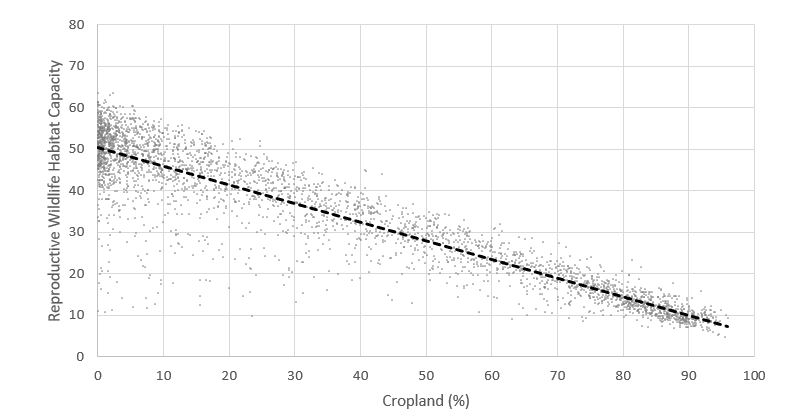

In 2015, WHCF varied from Moderate to High among Provinces resulting in a National rating of High (table 4). Nationally, the largest proportion of land in the agricultural extent was classified as having High WHCF (45.67%) followed by Moderate (21.77%), Low (21.01%), Very High (11.53%) and Very Low (0.02%). WHCF follows similar patterns as WHCR but is generally less restrictive indicating cover types used for breeding are more limiting for terrestrial vertebrates on agricultural land. Table 5 shows the proportion of national/provincial agricultural land in each WHCF class and figure 6 shows the spatial distribution of this information across the agricultural extent of Canada. As with WHCR, WHCF showed a negative relationship with the proportion of the landscape under Cropland (figure 7).

Description of Figure 5

Figure 5 is a scatter plot showing the relationship between reproductive wildlife habitat capacity on the y-axis and percent crop on the x-axis for 2015. There is an inverse linear trend between reproductive habitat capacity and percentage of crop land where the reproductive habitat capacity linear trend line declines from an index value of 50 at 0% cropland to approximately 8 at 95% cropland

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | %Change/Year 2000-2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 46.20 (H) | 45.72 (H) | 44.91 (H) | 44.72 (H) | -0.11 (SD) |

| Alberta | 41.46 (M) | 41.39 (M) | 41.03 (M) | 40.60 (M) | -0.06 (S) |

| Saskatchewan | 36.45 (M) | 36.65 (M) | 36.35 (M) | 35.96 (M) | -0.04 (S) |

| Manitoba | 36.29 (M) | 36.35 (M) | 36.10 (M) | 35.68 (M) | -0.04 (S) |

| Ontario | 37.58 (M) | 37.41 (M) | 37.08 (M) | 36.90 (M) | -0.05 (S) |

| Quebec | 44.50 (H) | 44.19 (H) | 43.88 (H) | 43.73 (H) | -0.05 (S) |

| New Brunswick | 51.68 (H) | 51.01 (H) | 50.48 (H) | 50.28 (H) | -0.10 (SD) |

| Nova Scotia | 47.46 (H) | 46.66 (H) | 46.01 (H) | 46.02 (H) | -0.10 (SD) |

| Prince Edward Island | 39.03 (M) | 38.76 (M) | 37.60 (M) | 37.53 (M) | -0.11 (SD) |

| Newfoundland | 50.61 (H) | 50.48 (H) | 50.39 (H) | 50.37 (H) | -0.02 (S) |

| Canada | 41.79 (M) | 41.60 (M) | 41.17 (M) | 40.91 (M) | -0.07 (S) |

| 2000-2015 | Large Increase | Moderate Increase | Slight Increase | Stable | Slight Decrease | Moderate Decrease | Large Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 60.19 | 28.52 | 9.02 | 2.27 |

| Alberta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 87.36 | 11.40 | 1.06 | 0.17 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 88.98 | 8.91 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Manitoba | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 91.72 | 4.66 | 2.22 | 0.77 |

| Ontario | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 96.63 | 3.14 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Quebec | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 87.46 | 12.38 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| New Brunswick | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 57.63 | 35.87 | 4.67 | 1.68 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 44.65 | 45.59 | 9.11 | 0.66 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 24.05 | 70.02 | 5.93 | 0.00 |

| Newfoundland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Canada | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 84.70 | 12.45 | 2.13 | 0.59 |

Description of Figure 6

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial distribution of feeding wildlife habitat capacity among state classes in the Canadian agricultural extent in 2015, color coded based on the capacity level from very low to very high.

Description of Figure 7

Figure 7 is a scatter plot showing the relationship between feeding wildlife habitat capacity on the y-axis and percent crop on the x-axis for 2015. There is an inverse linear trend between feeding habitat capacity and percentage of crop land where the reproductive habitat capacity linear trend line declines from an index value of 50 at 0% cropland to approximately 8 at 95% cropland

| 2000-2015 | Large Increase | Moderate Increase | Slight Increase | Stable | Slight Decrease | Moderate Decrease | Large Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 40.74 | 26.78 | 15.29 | 16.90 |

| Alberta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 73.61 | 22.73 | 2.77 | 0.89 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 84.94 | 10.05 | 2.38 | 1.59 |

| Manitoba | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 86.84 | 7.43 | 1.20 | 3.03 |

| Ontario | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 89.59 | 8.79 | 1.47 | 0.00 |

| Quebec | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 80.22 | 17.11 | 2.20 | 0.03 |

| New Brunswick | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 33.58 | 43.97 | 14.31 | 7.98 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 21.11 | 36.24 | 29.48 | 12.98 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.09 | 49.62 | 40.36 | 5.93 |

| Newfoundland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.96 | 88.13 | 5.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Canada | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 74.71 | 16.71 | 4.74 | 3.28 |

Trend (2000-2015)

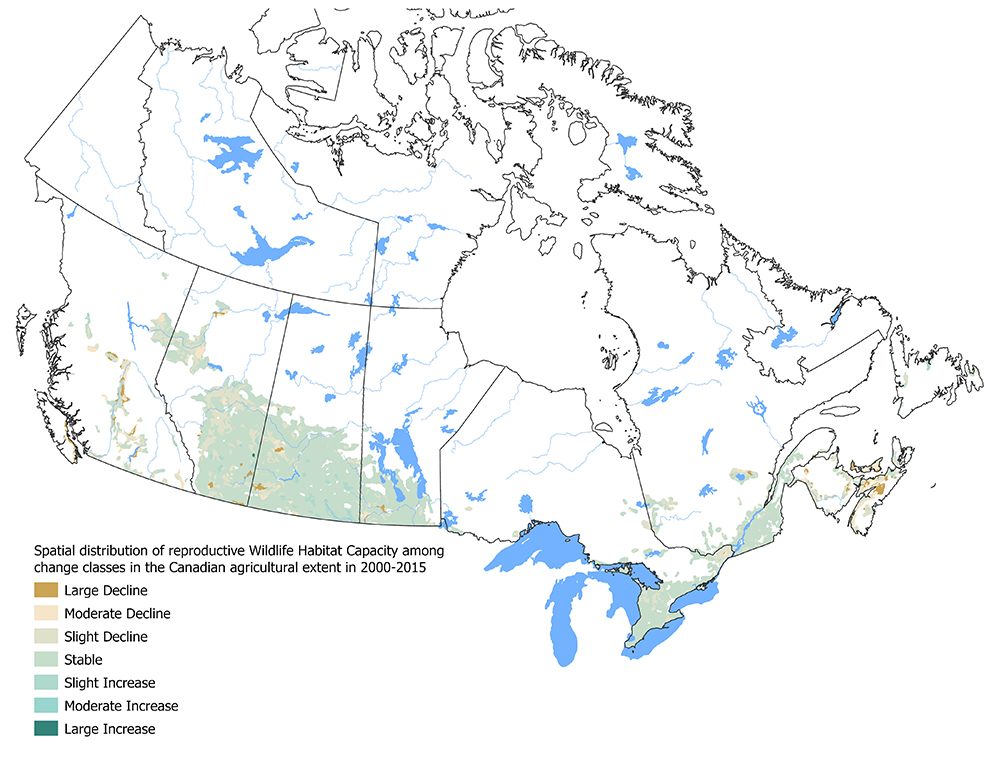

Reproduction

WHCR had varying rates of change among provinces ranging from Stable (-0.02%/year) to Slight Decline (-0.16%/year), resulting in a average national trend of Stable (-0.08%/year). Table 2 shows Provincial and National average WHCR for each study year and average rate of change/year over 15 years. Nationally, habitat capacity for reproduction was Stable on 74.71% of land within the agricultural extent, Declined on 24.72% and Increased on 0.57%. Table 6 shows the proportion of national/provincial agricultural land in each HCR trend category and figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of trend information across the agricultural extent of Canada. Nationally, WHCR trend resulted from change (one cover type to another) on 3.11% of land cover in the agricultural extent. The main drivers of habitat capacity decline were the loss of important natural and semi-natural cover types. This included loss of Managed Grassland (-0.55%), Woodland (-1.94%) and Wetland (-0.09%). The overall increase in Annual Cropland (0.98%) and decrease in Perennial Cropland (-0.31%) and Unimproved Pasture (-0.21%) had a negative impact on habitat capacity. The expansion of settlements (0.45%) also contributed to habitat capacity decline.

Description of Figure 8

Figure 8 illustrates the spatial distribution of reproductive wildlife habitat capacity among change classes in the Canadian agricultural extent in 2000-2015, color coded based on the capacity level changes, from a large decline in reproductive capacity to a large increase in wildlife habitat capacity.

The main drivers of WHCR change differed regionally. Across the Prairie Ecozone, the loss of important Managed Grassland habitat was a key driver of habitat capacity decline. Reduction of Unimproved Pasture, Wetlands and Perennial Cropland and expansion of Annual Cropland also contributed to habitat capacity declines in areas of the Prairies. In British Columbia and the Maritimes, forest harvest was a major driver of habitat capacity decline. Much of this activity was related to the forest sector and not attributable to agricultural land use. However, this dynamic land cover change impacted species occupying the broader land base within Canada's agricultural extent. In these areas, the loss of Perennial Cropland also negatively impacted habitat capacity. In the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, urban expansion lowered habitat capacity. In Central Canada, the main drivers of habitat capacity decline were the expanded share of Annual Cropland and Settlements combined with the reduction of Perennial Cover, Unimproved Pasture and Woodland.

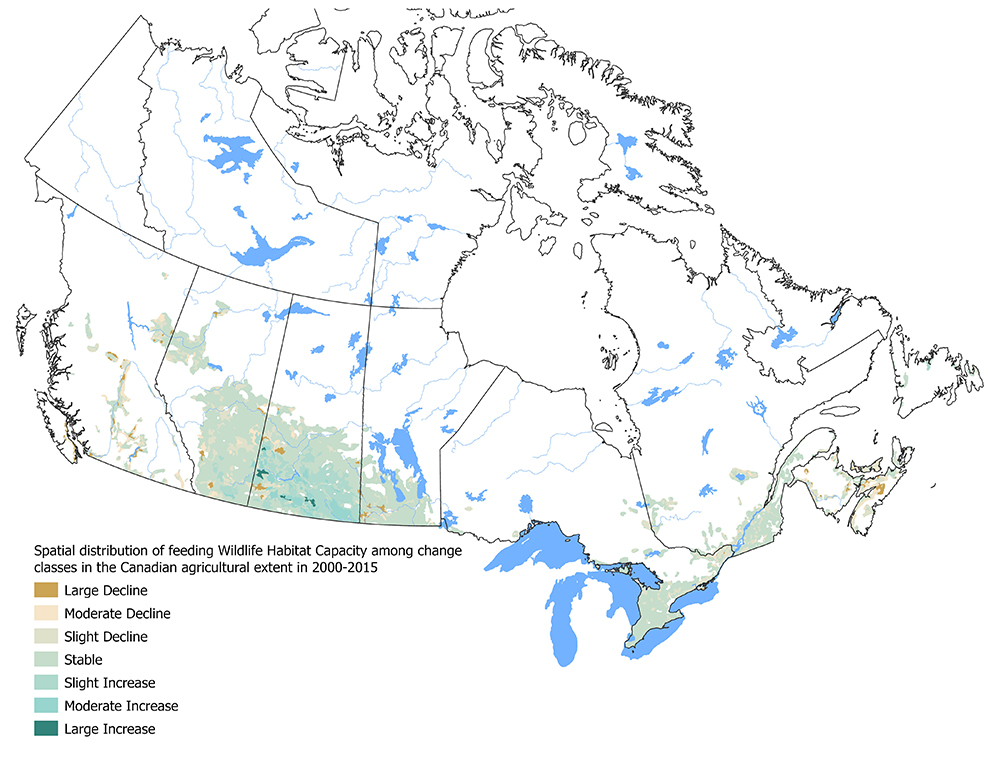

Feeding

WHCF trends followed similar patterns to that of breeding but exhibited a slower rate of change. Among provinces, WHCF change ranged from Stable (-0.02%/year) to Slight Decrease (-0.11%/year), resulting in a national average trend of Stable (-0.07%/year). Table 4 shows Provincial and National average WHCF for each study year and average rate of change/year over 15 years. Nationally, WHCF was Stable on 84.70% of land within the agricultural extent, Declined on 15.17% and Increased on 0.12%. Table 7 shows the proportion of provincial/national agricultural land in each habitat capacity trend category and figure 9 shows the spatial distribution of this information across the agricultural extent of Canada. Both national and regional drivers of feeding habitat capacity trends were the same as those for breeding but showed gentler rates of decline.

| 2000-2015 | Large Increase | Moderate Increase | Slight Increase | Stable | Slight Decrease | Moderate Decrease | Large Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 60.19 | 28.52 | 9.02 | 2.27 |

| Alberta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 87.36 | 11.40 | 1.06 | 0.17 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 88.98 | 8.91 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Manitoba | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 91.72 | 4.66 | 2.22 | 0.77 |

| Ontario | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 96.63 | 3.14 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Quebec | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 87.46 | 12.38 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| New Brunswick | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 57.63 | 35.87 | 4.67 | 1.68 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 44.65 | 45.59 | 9.11 | 0.66 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 24.05 | 70.02 | 5.93 | 0.00 |

| Newfoundland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Canada | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 84.70 | 12.45 | 2.13 | 0.59 |

Description of Figure 9

Figure 9 illustrates the spatial distribution of feeding wildlife habitat capacity among change classes in the Canadian agricultural extent in 2000-2015, color coded based on the capacity level changes, from a large decline in feeding capacity to a large increase in wildlife habitat capacity.

Response options

It is recognized that biologically diverse agro-ecosystems tend to be healthy, resilient and productive, providing a strong foundation for sustainable agriculture. However, farming is a business driven by markets and commodity prices, which make it challenging to balance high shorter-term productivity with the long-term health of the agro-ecosystem as a whole. Conserving habitat for wildlife poses a particularly difficult challenge because the most profitable agricultural land uses, such as high-value annual crops, may compete with the natural and semi-natural land-cover types that are required to maintain viable populations of many species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians within the agricultural landscape. Habitat loss and fragmentation caused by wetland drainage, woodland clearing and cultivation of grasslands and marginal land are key drivers of declining wildlife habitat availability on farmland. Given that most agricultural land in Canada is privately owned, the activities and decisions producers make can have a major impact on wildlife habitat.

Most producers understand the production/conservation conundrum and seek meaningful solutions within the economic realities of their livelihood which is dependent on farming. The development and delivery of a suite of beneficial management practices (BMPs) designed to improve wildlife habitat on farmland can provide guidance and decision support to producers' conservation efforts. Through environmental farm planning activities, producers learn about the impacts their farming operations can have on wildlife and about the BMPs they can implement to address these issues. These BMPs include managing riparian areas and woodlots; converting marginal cropland to permanent cover; planting or maintaining shelterbelts and hedgerows; delaying haying; and conserving wetland, wetland buffers, and natural and semi-natural lands. BMPs focused on the conservation of natural and semi-natural cover provide an important co-benefit by sequestering carbon and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

Conservation strategies at the farm scale can be most successful when they are aligned with conservation targets established at a broader landscape scale such as a watershed, municipality, provincial, or even national level. Initiatives that develop attainable wildlife habitat objectives can inform land-use planning and options to maintain or enhance wildlife on agricultural lands in a way that is compatible with farming activities.

For more information

Wildlife Habitat Availability on Farmland, plain language summary

Related indicators

The Soil Cover Indicator summarizes the effective number of days in a year that agricultural soils are covered by vegetation, crop residue or snow. When combined with the Wildlife Habitat Capacity Indicator, it provides a snapshot of biodiversity potential on farmland in Canada.

Additional resources and downloads

Discover and download geospatial data related to this and other indicators