Table of contents

- Soil salinity in Canada: why does it matter?

- What causes soil salinity?

- Risk of Soil Salinization – the indicator

- Soil salinity in Canada – current state and the change over time

- How can soil salinity be reduced?

Summary

- Soil salinization - the build-up of excess salt in soil – is a significant threat to agricultural soils and water resources in the Prairie provinces.

- It can decrease agricultural productivity, reduce economic returns, and lead to deteriorated water resources.

- The Risk of Soil Salinization Indicator measures the risk of salinization of soils from agricultural activity and other factors in the Prairie provinces. It also measures whether this is changing over time.

- Risk has declined greatly in the Prairies. In 2016, 88% of the land had very low risk of soil salinization

- The risk of soil salinization is still a concern in some areas.

- The risk of soil salinization can be decreased by effective soil-water management that limits the movement of salts through the landscape. Some examples include reducing the use of summerfallow, increasing the use of perennial forages, and implementing drainage practices.

Soil salinity in Canada: why does it matter?

Soil salinization - the build-up of excess salt in soil – is a significant threat to agricultural soils and water resources in the Prairie provinces. As soil salinization increases, plants experience drought-like conditions and lose their ability to absorb sufficient water. This can reduce seed germination, nutrient uptake, plant growth, and crop yield. Moderate, or severe, soil salinity can reduce crop yield by at least 50% for most cereal and oilseed crops. Soil salinization can also limit the range of crops that can be grown. Some elements in saline soils can also be toxic to plants. In some cases, soil salinity may lead to non-productive soils.

Together, these impacts reduce economic returns to farmers. In 2006, it was estimated that approximately 1 million hectares of Prairie soils had moderate to severe soil salinity. In the 1980s, it was estimated that soil salinity reduced Canadian farmers’ annual income by $257 million.

In addition to impacts on agriculture, salt from saline soils can also move to waterways leading to a deterioration of valuable local and regional water resources. It is expected that climate change could increase the risk of soil salinization because of increases in soil moisture deficits.

The Government of Canada must report on soil salinity on farmland. This helps Canadians and other countries know if Canada’s farmlands are healthy and where improvements to farming practices need to be made.

What causes soil salinization?

Soil salinization is a natural process. It occurs in regions where moisture deficits are common and where the soils and groundwater have high concentrations of mineral salts (such as sodium, calcium, and magnesium sulphate). It occurs most rapidly in dry regions after wetter-than-normal years. Elevated water tables move salts close to the soil surface. When water is removed, through transpiration and evaporation, salts become concentrated in the soil. Over time, this process leads to white salt crusts on the soil surface or salt crystals within the soil profile.

Soil salinization is influenced by natural environmental factors including water deficits, topography, the salt content of the soil parent material and underlying geologic formations, and water movement within the soil.

Although salinization occurs naturally in some landscapes, land-use practices can influence the amount, and extent, of salinization by altering hydrological pathways. Land-use practices that use water efficiently where it falls reduce ground-water salinity and decrease the extent of salt-affected areas. Agricultural practices such as continuous cropping, or growing perennial forages in upland areas, reduce water leaching through the soil. On the other hand, summerfallow and irrigation can elevate the water table allowing salts to concentrate in soil; this can add salts to groundwater which can spread to other areas.

Sensitivity to soil salinity varies with crop type and stage of development. For example, barley is more tolerant than wheat in weakly saline soils; brome grass and sweet clover are tolerant of moderately saline soils; and sugar beets are sensitive to low levels of salinity during the germination and emergence stages of growth.

Risk of Soil Salinization Indicator

The Risk of Soil Salinization Indicator measures the risk of salinization of soils from agricultural activity and other factors in the Prairie provinces. It also measures whether this is changing over time. It considers the current soil salinity and a number of landscape and climate factors: topography (slope position and steepness), soil drainage and growing season climate moisture deficits. It also considers land use data from the federal Census of Agriculture. This includes the amount of permanent cover, annual crops and summerfallow. Soil salinity experts rate the risk of each land-use type according to how much it influences soil salinity. Salinity risk increases, in order, from annual cropland to permanent cover to summerfallow. The proportion of each land-use type in an area, is used to assign overall risk related to land-use type. Soil salinity risk is categorized into five relative risk classes: very low, low, moderate, high and very high.

The Government of Canada calculates the Risk of Soil Salinization Indicator every five years. It helps the Government know how soil salinity on farmland is changing over time and identify where changes to farming practices are needed.

Soil salinity in Canada – current state and the change over time

In 2016, the risk level of salinity on farmland in the Prairies was classified as “desired,” with 88% of land rated as having a very low risk of salinization.

Across provinces, the risk of soil salinization was higher in areas of Alberta and Saskatchewan with arid brown and dark brown soil zones. In Manitoba, the risk is higher in areas with humid, black soils. Increased risk, here, is caused by other risk factors such as relatively level landscapes, poor drainage, and near-surface saline groundwater.

Risk of Soil Salinization on the Canadian Prairies 2016

The risk of soil salinization in the Prairies has declined since 1981. Over this period, the land area in the low, moderate, high and very high risk classes decreased by 14%, 5%, 1% and 3%, respectively. At the same time, the area of land in the very low risk class increased by 22%. Area in the very low risk class increased by 36% in Saskatchewan, 12% in Alberta and 10% in Manitoba. Risk decreased by at least one risk class in 59% of regions in Saskatchewan, 28% of regions in Manitoba and 25% of regions in Alberta. Across the Prairies, only one region in Manitoba showed an increase in risk class (from low to moderate).

Change in Soil Salinization risk on the Canadian Prairies 1981-2016

Soil salinization has decreased over time, mainly, because of a reduction in summerfallow and an increase in the use of permanent cover. Since 1981, the area of summerfallow has decreased across the Prairies by over 90% (8 million ha). The decrease in the use of summerfallow has occurred for many reasons: the adoption of management practices that maximize plant production and use of moisture (for example, use of chemical fertilizers, extended crop rotations, continuous cropping); use of chemical herbicides; conversion of marginal land to permanent cover or pasture; and awareness among producers of the long-term effects of summerfallow and conventional tillage practices. With some exceptions, the area of permanent cover has increased over time. Since 1981, the area of permanent cover in the Prairies increased by 6% (2.3 million ha). Since 2011, however, the area of permanent cover declined because of market shifts toward the cultivation of annual crops.

How can soil salinity be reduced?

While soil salinity risk has decreased across the Prairies in recent years, it is still an issue for some producers. This is especially true when water tables are high after wetter-than-normal years. Reducing the risk of salinization and improving saline soils requires effective soil-water management. Best Management Practices can help achieve this by reducing movement of excess water and increasing the use of precipitation by plants where it falls. These will help control the movement of salts throughout the landscape.

Effective land and water management practices:

- Reduce use of summerfallow.

- Increase use of perennial forages, pasture and tree crops.

- Adopt snow management techniques (for example, preventing large drifts) to evenly distribute snow and reduce ponding in the spring.

- Increase use of no-till and minimum-till to allow precipitation to encourage more uniform infiltration of precipitation.

- Effectively use fertilizers and manure to support healthy crop growth and maximize water uptake.

In areas where water tables are high, Best Management Practices that lower the water table can help:

- Plant deep-rooted, high-moisture-use perennial plants. This will help dry out the subsoil and draw down the water table.

- Incorporate salt-tolerant crops in areas where salinity is a problem. This will maximize water use and reduce salt movement to the soil surface.

- Establish perennial forage, or tree crop strips, to reduce groundwater flow to at-risk areas.

- Use subsurface, plastic, and tile drainage to remove water and salts.

- Use surface drainage to reduce recharge.

- Monitor depth of ground water in sensitive areas to help in land-use planning. This will also help determine the most appropriate Best Management Practices to implement.

More work is needed to:

- understand how reduced (conservation) tillage practices impact the movement of water and soil salinity

- develop a wider range of salt-tolerant crops for use in high-risk areas

- coordinate efforts across conservation districts and government agencies, since groundwater flow often crosses administrative lines.

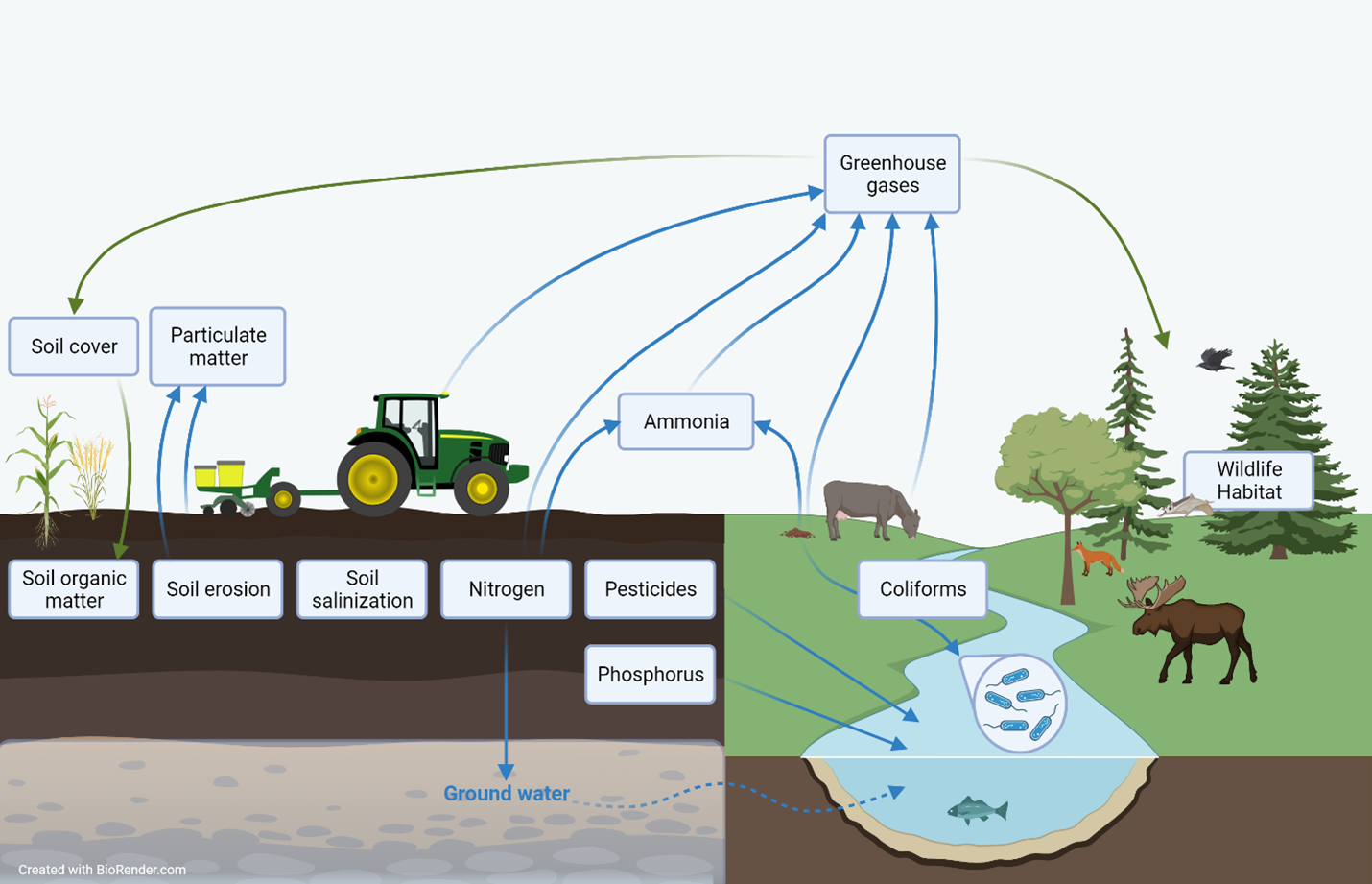

Description of the image above

An infographic showing an agricultural landscape with crops, a tractor, soil and grazing livestock adjacent to a natural landscape with a watercourse, forest and wild animals. Info boxes are placed to show to which element of the landscape each agricultural sustainability indicator pertains. Arrows connect some of the info boxes to show interrelationships. One info box is present for each of the following indicators: Soil cover, particulate matter, soil organic matter, soil erosion, soil salinization, nitrogen, pesticides, phosphorus, ammonia, greenhouse gases, coliforms and wildlife habitat.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's agri-environmental indicators (AEIs) provide a science-based snapshot of the current state and trend of Canada’s agri-environmental performance in terms of soil quality (soil organic matter, soil erosion, soil salinization), water quality (nitrogen, pesticides, phosphorus, coliforms), air quality (particulate matter, ammonia, greenhouse gas emissions) and farmland management (agricultural land use, soil cover, wildlife habitat). While indicator results are presented individually, agro-ecosystems are complex, so many of the indicators are interrelated. This means that changes in one indicator may be associated with changes in other indicators as well.

Learn More

Related indicators

- The Soil Erosion Indicator tracks the health of Canadian agricultural soils as it relates to the risk of erosion from tillage, water and wind.

- The Soil Organic Matter Indicator tracks the health of Canadian agricultural soils as it relates to soil carbon content.

Additional sources and downloads

Discover and download geospatial data related to this and other indicators.